A group of Sahrawi women demonstrates with flags on the street in the city center during a demonstration. Protesters marched in the Spanish capital to demand respect for international legality in Western Sahara, and its decolonization by Morocco. Photo by SOPA Images.

Kang-Chun Cheng (KC) is a freelance writer and photographer based in Nairobi, covering stories about the environment, foreign aid, and outdoor adventure for outlets like Atmos, The New York Times, Mekong Review, Al Jazeera, Post Magazine, Bloomberg, Christian Science Monitor, and Climbing. Her work can be found on Instagram at @takeme.north and here: kang-chun-cheng.format.com.

A few years ago, as the world was distracted by the peak of the pandemic, then-President Trump brokered a deal between two of the world’s occupier states near the end of his administration. It was the Abraham Accords: in exchange for Morocco normalizing relations with Israel, the U.S. would recognize Morocco’s claim over the occupied territory of Western Sahara. This amounted to turning a blind eye to the plight of the hundreds of thousands of Sahrawis living in Africa’s last colony. This wasn’t the first time the Western world lent its support to a brutal regime to violently suppress a minority, and it wouldn’t be the last.

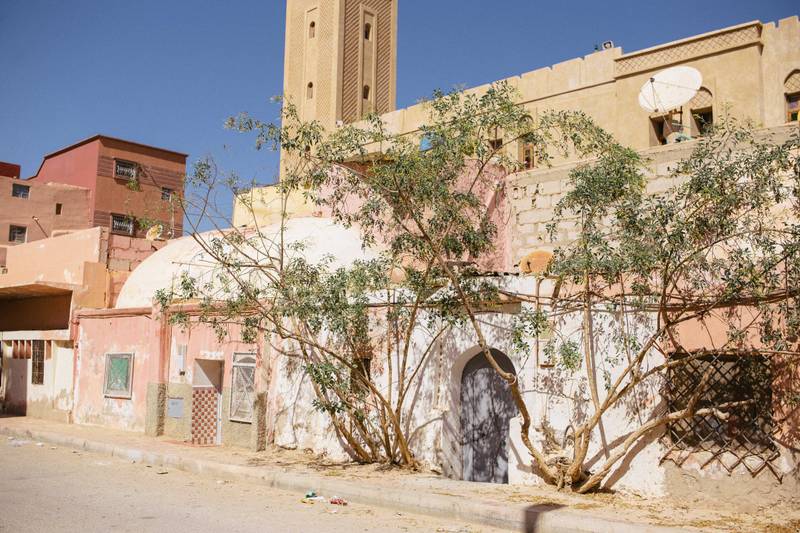

Before we got to Western Sahara, our fixer advised us not to call it that—just say ‘south Morocco,’ he said, to be discreet. Most Sahrawis live in Laayoune, Western Sahara’s biggest city and unofficial capital. It’s a highly surveilled place, sprung from the sands of the Sahara, the streets teeming with armed Moroccan security. Here, it’s illegal to raise the Polisario Front party flag, a Sahrawi nationalist and liberation organization that the United Nations considers a legitimate representative of the Sahrawi people. Even peaceful advocacy for self-determination, deemed oppositional by Morocco, is met with harsh clampdowns.

In 2022, I travelled to the occupied city of Laayoune with journalist Jacob Kushner to report on how Morocco’s government had weaponized the COVID-19 pandemic as another excuse to persecute Sahrawi independence activists. One of the tell-tale signs of the occupation is how the Moroccan flag is draped everywhere, to an extent not seen in Morocco.

In Laayoune, a lady buys olives at a shop covered by the Moroccan flag.

The streets of Laayoune are generally immaculate, with signs of the Moroccan occupation everywhere.

After the Six-Day War, Israel captured the Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip, West Bank, Jerusalem, and Golan Heights (the United Nations considered Israel’s claim to these regions unlawful.). Despite Israel’s decisive military victory, the status of these territories propagated contention with the nascent nation’s Arab neighbours. In 1979, Israel normalised relations with Egypt by returning the Sinai Peninsula but retained control of the others, occupying the West Bank and Gaza with military force. At present, more than half a million Israeli settlers inhabit the West Bank, 200,000 in East Jerusalem, and 20,000 in unofficial settlements (unsanctioned zones) alongside Palestinian residents.

These settlements have all been deemed illegal by the United Nations, in violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which states that a nation cannot move civilians into an area that it occupies during wartime. Israel disputes this, saying that the West Bank and East Jerusalem were previously never officially part of any formal Arab nation at the time.

Around this time, Morocco was sending settlers to occupy the freshly abdicated region. Spain had ruled a slice of the Sahara since 1884, leaving only in 1975 as political turmoil and violence heightened to untenable degrees: the newly minted Polisario Front was driven to overthrow colonial rule via armed struggle. Spain essentially left Western Sahara to be divided up between Morocco and Mauritania.

Morocco sent more than 350,000 nationals to ‘Morrocanize’ the disputed territory. This settler-occupation became known as the Green March. Moroccans have displaced at least 200,000 Sahrawis—the majority of the indigenous population—since 1956. Today, over 173,000 Sahrawi refugees live across five camps in Algeria’s Tindouf province, bordering Mauritania, Morocco, and Western Sahara. Access to clean water and education remain abject challenges; 30% of refugees face food security issues. Some Sahrawis have been displaced for more than 45 years.

The cognitive dissonance of the Moroccan government and nationals alike in supporting the Palestinian cause while turning a blind eye to their own occupation of Western Sahara can be hard to reconcile. From pledges to resuscitate negotiations for a two-state solution to waving a Palestinian flag after defeating Spain—its former colonizer—in the 2022 World Cup win, the concept of liberation appears prevalent in the Moroccan sphere but has never extended to its own occupied territory.

Palestine flags in action during the FIFA 2022 World Cup group match between France and Morocco, Al Bayt Stadium, Doha, 14/12/2022 Featuring: Palestine flags Where: Doha, Qatar When: 14 Dec 2022 Credit: Anthony Stanley/WENN

One Sahrawi translator we worked with explained how she was born and raised a refugee in one of these camps. She says that until she had the chance to leave as an adult, she thought the harshness of refugee life was how everyone lived. She didn’t know that life could be different.

Today, Moroccan settlers account for nearly two-thirds of the half-million residents of Western Sahara. Since the onset of the Green March, the Polisario Front has struggled to garner support from Algeria and Libya. Multiple guerilla wars raged on, fending off Mauritania in the southwest and battling the Moroccan Army across stretches of sand. Mauritania ceded its claim to the Western Sahara in 1979, but conflicts with Morocco simmered until 1991. After years of mediation attempts by the African Union and the UN, a ceasefire was brokered. The estimated death toll ranges between 10,000-20,000 people. At present, the Kingdom of Morocco controls nearly 85% of Western Sahara.

There’s the Berm, the longest minefield in the world, that the Kingdom of Morocco constructed with assistance from the American and Israeli governments through arms sales. This 1,600-mile-long fortified sand barrier bifurcates Moroccan-controlled areas on the west from eastern Polisario-controlled areas.

Other times, the clout is more subtle, wielded by way of extensively manicured gardens proliferating across Laayoune, Western Sahara’s unofficial capital city. This juxtaposition was viscerally jolting—why such verdant landscaping in a desert city? One early morning, on a jog across the bridge leading away from Laayoune to the desert, over the seasonal el Sakia Hamra River, we saw city employees washing down the street with copious amounts of water, a strange sight in a place where water is so scarce. Later on, a documentary friend who had previously filmed in Western Sahara told me it’s a projection of power—Morocco’s way of demonstrating just how scrupulously they’re taking care of Western Sahara— to deflect allegations of abuse.

1991 was also the year the UN recognised the right of Sahrawis to hold a referendum to vote for independence, even establishing a mission for the cause. But for more than three decades, Morocco has refused to let the referendum take place. In late 2020, the ceasefire collapsed when Morocco seized a section of the UN buffer zone to circumvent blockades by Polisario activists; shortly after, Algeria discontinued diplomatic relations with Morocco. In July 2021, Mary Lawlor, United Nations special rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, advocated for peace: “I urge the Government of Morocco to cease targeting human rights defenders and journalists for their work, and to create an environment in which they can carry out such work without fear of retaliation.”

Lawlor told the stories of two human rights defenders, Naâma Asfari and Khatri Dadda, who have been detained since 2010 and 2019, respectively, as well as activist Sultana Khaya’s house arrest and alleged sexual assaults by Moroccan authorities. Moroccan authorities’ persistent targeting of Khaya, a long-time Sahrawi independence activist, speaks to the Kingdom’s intolerance of opposition to their authoritarianism. Healthcare is a weaponized topic in Western Sahara, Khaya says in an encrypted call. When the first COVID-19 vaccines became available, Morocco did not really bother to push a vaccine on Sahrawis the way they did on Moroccans, she continued. “We were scared and skeptical. We have no trust in the Moroccan authorities. As human rights defenders, we could be targeted.”

In September 2022, the African Court on Human and People’s Rights declared the Saharawis’ right to self-governance. However, the Kingdom of Morocco repeatedly refuses to acknowledge legal violations of human rights.

Despite a lack of international media coverage, tensions still bubble up in the region. Experts interpret Morocco’s alleged attacks on Algerian and Mauritanian civilians—a 2021 Moroccan drone strike in Polisario-controlled Western Sahara, killing three Algerian truck drivers; a 2022 attack where Algeria accused the Moroccan air force of killing three civilians near the Mauritanian border—as attempts to disseminate conflict across the rest of the region.

On our last night in Laayoune, we enjoyed a feast of camel meat and rice with another of our translators, prepared by his mother, along with a few of their friends. One of them is a truck driver, carrying produce as far as Senegal. The checkpoints are an absolute hassle, he says over sweet Sahrawi tea. But you learn how to navigate them and work your way past the authorities. Like everyone else in Laayoune, he’s learned how to find a sense of normalcy despite an occupation. For all Sahrawis, one that could dip at any moment.

At midday, the heat in Laayoune–a city born of the Sahara desert–is intense.

A taxi in Laayoune, Western Sahara’s unofficial capital, driving past a billboard reminding residents of Morocco’s rule.

The Kingdom of Morocco has long used money and its military to exert control over Western Sahara. According to Transparency International, a nonprofit focused on combating global corruption, the nation has spent more than $862 billion on infrastructure, military, and unemployment benefits in Western Sahara.

For its part, Europe both depends on and profits from Sahara’s apartheid, complicit in Morocco’s plundering of Western Saharan resources, namely phosphate and fish. The EU is Morocco’s largest trade partner (making up 49% of its goods trade in 2022), as well as its biggest foreign foreign investor. In 2020, Morocco sold nearly 1.3 billion worth of fish, many illegally sourced from Western Saharan waters, and has granted Morocco hundreds of millions of dollars to finance border security projects to keep refugees from flooding Europe’s shores. Thousands of migrants have been arrested while attempting to traverse a fence into the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla—hundreds injured, and dozens killed.

In 2020, Trump’s administration shifted political allegiance away from Western Sahara’s right to vote for independence to Morocco’s announcement to occupy it more permanently. Two years later, Spain followed suit. This geopolitical shift has palpable ramifications for millions of Sahrawis In a 2021 statement, Amnesty International wrote that “Moroccan authorities have intensified their spate of violations against pro-independence Sahrawi activists through ill-treatment, arrests, detentions and harassment in an attempt to silence or punish them for their peaceful activism against Morocco’s push to further consolidate its control over the disputed territory of Western Sahara.” The organisation has also described Moroccan authorities as having gone to ‘extreme lengths to brutally and unlawfully crush dissent from Sahrawi activists.’

A bridge over the seasonal Saguia el Hamra river that bridges Laayoune from the Sahara Desert.

The Death of a Dissident

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Sahwaris’ distrust of Morocco seemed to increase. Some feared seeking vaccines or treatment from Moroccan hospitals, as I learned in the case of Mbarek Daoudi.

Daoudi, a former conscript soldier, had fallen out of favour with Moroccan authorities long before. In February 1976, he witnessed Moroccan soldiers massacre a Sahrawi family in Amgala, an oasis area controlled by the Polisario Front and the site of several clashes between the Moroccan Army and the rebel independence movement at the time.

Decades later, in 2013, he showed a French journalist and international rights activist the Sahrawi grave. Moroccan authorities were enraged. Three months later, authorities charged Daoudi with owning a firearm, which he inherited from his great grandfather from the French colonial era, along with 35 shotgun shells. According to Sahrawi attorney Cristina Martínez Benítez de Lugo, authorities also suspected a metal tube that they claimed he intended to turn into a weapon.

Daoudi was sentenced to prison, where he languished for 6 years as his health spiralled. At various times, authorities also apprehended two of Daoudi’s sons, prosecuting them for their political opinions. Human Rights Watch has reported on how Moroccan authorities have resorted to ‘unfair trial proceedings, digital and camera surveillance, harassment campaigns by media close to the royal court known as the Makhzen, physical surveillance, aggression and intimidation, and targeting of relatives of activists.”

“After his arrest, Mr. Daoudi was tortured along with his two sons and forced to sign a confession already drawn up by the Moroccan authorities,” according to a petition to the UN. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention—a confession he claimed he wasn’t permitted to read. Daoudi said he had no choice but to sign it under physical duress. He was placed in solitary confinement and denied access to a lawyer, the UN found. His family said that he once went on a 52-day hunger strike to protest his pre-trial detention.

In 2018, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention determined Daoudi’s detention violated the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and that he should immediately be released, and expressed “(concern) about the allegations of abuse relating to Mr. Daoudi’s two children.”

“Mr. Daoudi has the right to express a political opinion, including advocating for the self-determination of the Sahrawis,” the report noted. It wasn’t just Daoudi–Moroccan authorities also came after his sons. At one point, four of his five children were also imprisoned in different cities across Morocco. But in September 2021, Daoudi died from what his family claims was COVID-19 contracted from prison at age 65.

It wasn’t easy to report in Western Sahara. We wanted to speak to Daoudi’s son, whom our translator had managed to put us in touch with. But we ultimately decided against it, for the safety of our sources and ourselves. Our translator assured us we’d all be detained on the spot if we attempted to visit their home. It was only later that we attempted to contact Daoudi’s family–through a translator on an encrypted call. That’s when his son told us their story.

When we approached Moroccan ministries to learn their side of the story, we were stymied for months on end.

On the ground, we spoke with critics and human rights defenders in Western Sahara, who told us that COVID-19 provided yet another excuse for Morocco’s leaders to penalize Sahrawi political opponents and media. Sahrawis were ordered to take vaccines from a government that many do not recognize or trust. In a world filled with disinformation powerful enough to manipulate elections, Sahwaris had a unique reason to distrust the vaccine: it’s the medicine of their oppressors.

Although protests come with high risks in Western Sahara (violent repression is a strong possibility), some activists and students in particular still practice active resistance. For instance, Khaya, an outspoken independence activist, lost an eye during one clash with Moroccan authorities yet continues to speak out about the need for Western Saharan autonomy.

“With young Sahrawi people, we have engagements in all kinds of spaces—COPs, human rights conferences—and we’re committed to speaking about Western Sahara. A lot of groups from Western Sahara, Laayoune, Sahrawi camps, and Spain are all engaged in the independence movement, not only physically but in media, on Instagram, to talk about human rights,” says 24-year-old Ahmedna Abdi M’barek, an activist with Juventud Activa Saharaui, who grew up in an Algerian refugee camp and is now studying law in France.

I got a firsthand look into the dark aspects of Moroccan healthcare. After leaving Casablanca and before reaching Laayoune, I got horribly sick as I often do abroad. Overnight, I came down with extreme fatigue and chills. It hurt just to walk. I checked into the nearest hospital, the International Health Clinic of Marrakech, where staff informed us in advance of the price for a consultation and routine blood test. When I went to settle the bill, they’d more than doubled the tab. A security guard blocked the exit to prevent me from leaving, making the hospital experience feel more like extortion than care.

Occupied Western Sahara is not a friendly place for journalists. The moment we arrived, a minder—a government security agent—was assigned to follow us wherever we went. We saw his shadow before we saw him: a small, dark silhouette of a man creeping along a wall at the edge of the city, while I took scene-setting photographs in the sand.

He wasn’t exactly skilled at his surveillance, or discrete. Once, fumbling for my hotel card on a main street in Laayoune after lunch, I stopped abruptly at a stand selling fresh pomegranate juice. The minder, who was following us too closely, nearly ran into us—he must have been distracted, too.

In occupied Western Sahara, Moroccan security services require hotel owners to inform them of foreigners’ passport numbers, dates, and comings and goings. For journalists, the surveillance is even more intense. Each day, while we were out, they searched our hotel rooms. One day, near the end of our week-long reporting trip, they attempted to place a bug in the fan above my journalist colleague Jacob’s shower. Security agents forgot to remove the chair they stood on to do it. When Jacob returned, the chair was still in the shower below the fan, muddy with bootprints. We asked our translator if they’d left it intentionally to intimidate us. He assured us the act wasn’t calculation but incompetence—that the Moroccan minders assigned to follow foreigners are the ones who are too inept to do anything else.

After the attempted bug in the shower, we decided it was time to leave Laayoune. We booked a flight to the Canary Islands, a skip across the Atlantic. At the airport, I was nervous. I clenched my stomach and tapped my fingers as the lady at immigration scrutinised my passport for ages. What had our minder written about us, I wondered, in their file? Would they confiscate my camera and memory cards? But I was an American journalist—not a Sahrawi or even a Moroccan one—with the freedom to leave. Boarding the small plane, I didn’t want to look back. The golden horizon was beautiful, with light streaming over puffy cumulus clouds. It felt wrong to enjoy such a view.

An old military base near the Port of Laayoune, a vestige from the era of Spanish colonialism.

Sahrawi boys go home after an afternoon of playing football in the Sahara desert.

Landing in Gran Canaria, I felt numb and then a bit nauseous. How could these soothing Atlantic waves in the land of Manchego and Jamón be the same ones I’d stepped into by the port of Laayoune, where daily life is overshadowed by a near-unimaginable brutality?

Once in a while, I think back to those Sahara nights. At dusk, the sky would bloom into the loveliest shades of peach and cotton candy pink. Calls to prayer sounded from the mosques, children scampering across cobbled streets, chasing after a soccer ball, or zooming past on bicycles. The sunlight danced across the sand dunes before fading into deep terracotta hues. Yet walking along the seemingly interminable desert, the trueness of that expanse somehow felt unreachable, not free from Morocco’s tightening grip.

Western Sahara has always been a waning plight to the rest of the world, focused on other war-torn and occupied places. Today, as the world rightly fixates on the more than 32,000 civilians massacred by Israel in the occupied territory of Gaza, I find myself worrying about the hundreds of thousands of vulnerable people in this Africa’s often-overlooked occupied land.

Our translator in Laayoune and Jacob Kushner contributed reporting for this piece.

The endless sands of the Sahara Desert, just outside Laayoune.