Portrait of Xiao by Vinayak

Vinayak (he/him) is a visual artist whose research-based practice leans heavily on material explorations, collective action, politics of archives and knowledge building. He is primarily engaged in investigations about the medium of photography itself, its possibilities, fallacies and promises that are dissected and explored mainly through the photobook object, play and exhibition making.

VINAYAK: I’m interested in meandering through the show while we conduct this interview. Can you give me a walkthrough and tell me more about the intriguing title?

XIAO: Layered Hills send off Glimmering Light is the starting line of a poem by Wen Tingyun1, which casts a blurry glimpse into the interiors of a lady’s bedroom while she is dressing up. But how can hills be layered and folded inside a room? This exhibition is a documentation of my research on the relationship between landscape, devices and poetry in the Chinese history of painting. Like most of my exhibition-projects, I start by doing research and reading books. I pick one book and dive into it; one book leads to other books, and so on. I start to wander in them, with them, not knowing where this process will bring me until, eventually, a sort of knowledge-net, woven by cross-referencing bibliographies is assembled. I see exhibition-making as a medium in itself, and the works are always specifically created for the exhibitions.

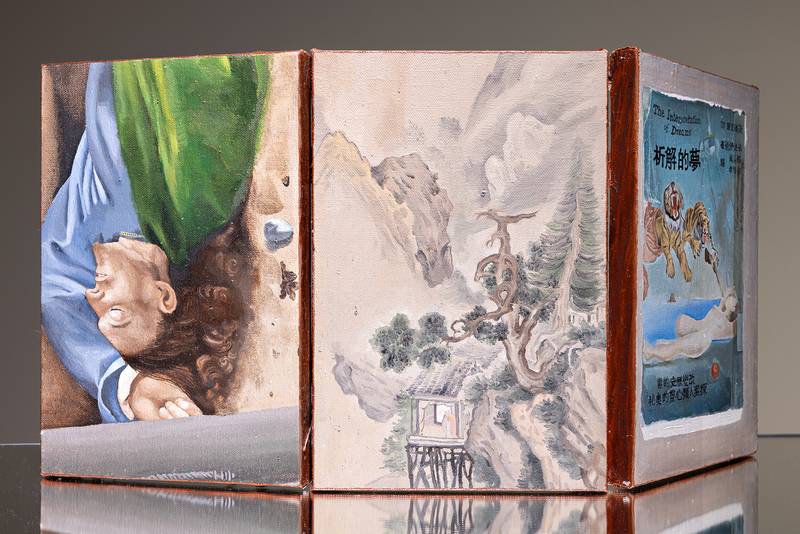

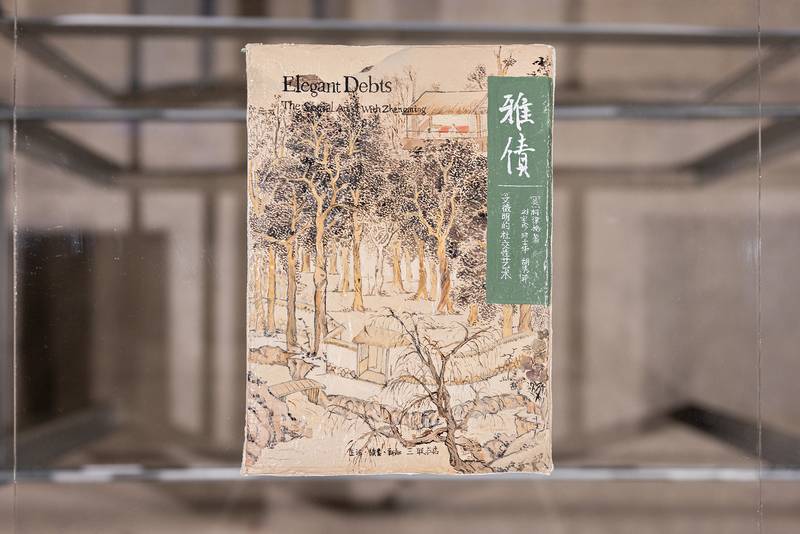

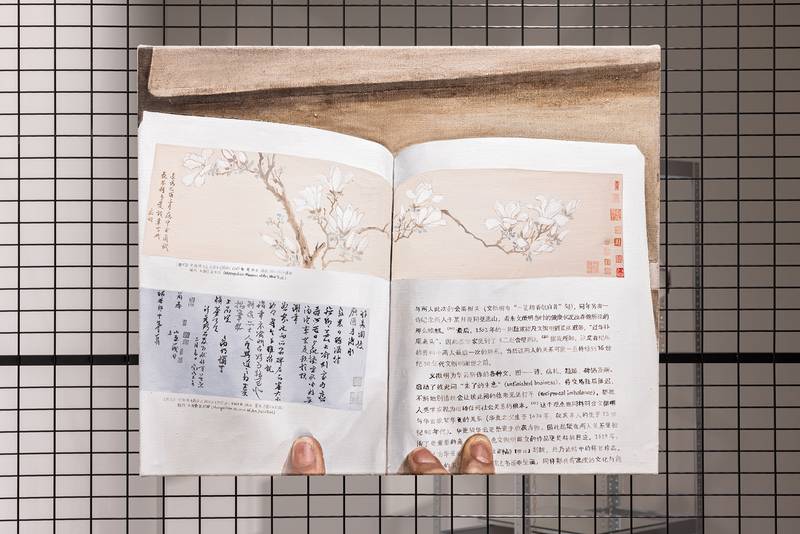

Here, you see many works – I call them book paintings. They are a series of canvases that are not just depicting the appearance of books but carry the weight of the (book)objects (that they represent). They’re titled after their weight in grams. I was very interested in the materiality of the painting and as well as the materiality of knowledge – how much weight does it take for something to be understood? For this exhibition, I created five book paintings. They are from the bibliography that I created for my study on the different topics of this exhibition – they’re both artworks to be displayed as well as an archive of testimonies of the research process and the many discourses that flow in this exhibition. Similarly, you can find this idea in the large screens that continue through the whole exhibition space, as well as the metal structures with mirrors used to host all the paintings.

Landscapes after Tang-dynasty poems (detail), oil on canvas, 30 x 62 cm, 2024. Photo by Xiao Zhiyu

Exhibition view Layered Hills send off Glimmering Light at Helsinki Art Museum, July 6 – September 1, 2014

Xiao Zhiyu, 565gr, oil on linen, heavy pigments, 24 x 17 cm, 2024, from the collection of Helsinki Art Museum

Could you elaborate on the many terms you lend from traditional Chinese poetic landscape painting tradition and how they inspired the exhibition making itself?

I recently discovered a fascinating historical practice among Chinese scholar-officials, or literati2, who would gather for events called bó gǔ. These were essentially private exhibitions held in a friend’s home, where they’d spend a few hours, or half a day, appreciating historic relics and objects from personal collections. It was almost performative in its fleeting, intimate nature. Reflecting on this, I realized how different it is from the Western concept of exhibitions, where objects are typically displayed in isolation and over much longer periods.

The temporalities of this collective viewing experience are often in direct contrast with the Western bourgeoisie idea of viewing art as a lone figure standing in front of a work of art to contemplate it in silence. In the bó gǔ, often a group of friends gathered together, and the experience involved intimate handling of the objects and new temporalities of experiencing scroll paintings. These experiences were built through a collection of fragments that often happened in a limited time; the group got to experience the material based on their request to the owner, hence not without also an element of performance and various negotiations and power relationships. Through existing historical documentation, we can see that bó gǔ often happened in outdoor garden spaces surrounded by large temporary painted screens mounted on wooden frames. The precise reason why they would do that still remains a mystery but allows one to speculate.

The idea of bó gǔ hence became the central curatorial framework for projecting this exhibition and the various elements that inhabit the space. I decided to create my own screen structures using collages created from my bibliography of the traditional paintings I encountered during my research.

The presence of large screens, with these images of screens which, if one looks closer, reveals more screens within screens, are you drawing parallels to our relationships with the current economy of screens?

I think screens are both images and functional objects. They delimit space as objects, but being images also requires that they break the borders between spaces. I find this fascinating because I see a resonance between the Chinese tradition of image-object making with some contemporary Western thinkers – like the thousand plateaus from Deleuze and Guattari’s or Hito Steryl’s notions on the cutting and circulation of digital images and their materiality.

Images on screens are fragmented and light, all the collages on the screens here are stretched in relation to their original proportions. It’s also interesting that we use the word ‘screen’ for both these ancient Chinese furniture and today’s digital devices. I wanted to highlight this interconnectivity across time, which was not just an etymological coincidence but also the nature of images and how we approach them.

Screens played an active role in bó gǔ, especially when they happened in an outdoor space. These large translucent screens painted on silk or paper carry representations of nature, constructing the set for the happenings. They build a site that allows projection, just like the literati surrounded by screens, and they suddenly cut you off from the ‘real world’ and transport you to new realms assisted by the objects in view.

The screen paintings also reflect on many ideas of representations of what is object, what is image and what constitutes the real. I find it super fascinating and full of possibilities, and I find this idea of layers, structures, and collective experience present in knowledge production. For example, (Xiao points at a specific detail on one of the large screens in the exhibition) in this collage, you see a painting by Zhou Wenju3, where four men are seen sitting together playing Go in front of a large screen that shows one of the four men laying on the bed in front of another screen depicting a painted landscape. In the case of this painting, it is the same man presented in the different spaces: the outward space of his public life engaging in intellectual activity with his other literati friends to the inner space of him as a husband or patriarch relaxing and being served in intimacy till the wild nature resembles his spiritual space, these layered spaces completes the image of a Confucian man and allows the viewers travel between layers.

At this point, we are interrupted loudly by museum security stopping an elderly woman reaching out to touch a book painting.

Exhibition view Layered Hills send off Glimmering Light at Helsinki Art Museum, July 6 – September 1, 2024

Elegant Debts, oil on linen, 60 x 73 cm, 2024 Photo by Xiao Zhiyu

The screens then become a sort of vehicle for dreaming. You communicate with it, within it, and I imagine, in a way, it starts to color your dreamscape, affecting its progression. What does dreaming mean to you?

Yeah. Another thing I encountered while doing my research is the screens’ relationship with sleep because, in the original Chinese tradition they were part of the bed. My conversation with Minna Törmä helped me a lot. I was reading her book Landscape Experience as Visual Narrative (2002), where she talks about the concept of Wǒ yóu, which literally translates as ‘traveling while lying down’. When you’re, for some reason, unable to see the world, you can still travel within landscape paintings, daydreaming with scrolls.

This piece here is a foldable triptych titled Landscapes after Tang-dynasty poems, the same as a painting from one of my favorite Chinese painters Sheng Maoye. The painting on the left is a reproduction of the detail of a sleeping man from a Renaissance painting that I found on my phone, and the one on the right is the image of the first edition of the Chinese translation of Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, that I have discovered in an exhibition about the brain in Fondazione Prada, Venice. The painting in the middle is a reproduction in oil from Sheng’s painting Lonely Retreat Overlooking a Misty Valley. In the image, you see a misty valley, a remote cottage in which a single man stands in front of the window and stares at the foggy void. I see this as a sort of daydreaming painting because Sheng certainly did not paint it onsite. We don’t know who the man is. He could be anybody, possibly a projection of an ideal Confucian figure, daydreaming of an ideal poetic lifestyle. These mounted screens were also part of beds, but they were often separated from the beds and became independent furniture. Imagine how romantic it could be to sleep on such beds. Dream is also very queer, it’s a site of freedom, conventional rules don’t apply there, and anything could happen. Some things are taken seriously, and some things are not. It’s serious when you want it to be serious and not taken seriously. If you don’t want it, then it’s just a dream. I forget it. Everything in this exhibition is connected by dreams and dreaming.

The exhibition uses familiar infrastructures of the archive, the metallic shelves, and the bibliography, suggesting its institutional origin. Could you share something about the choice of materials for the show and how it determines the experience of the exhibition?

Archives, systems of knowledge and the physical structures associated with them have always been a great fascination for me. My first encounter with these shelf structures was with Renée Green’s work Import/Export Funk Office at the Kunsthalle in Zurich, where similar shelves were used to construct a room that served as both physical space and somehow became the work itself. The shelves are recycled from my previous exhibition at SIC space, where I tried to transform the space into a fictional library. My shelves were, in a way, a citation of Green’s exhibition. I was drawn to the vitrines, glass viewing table and various kinds of shelves that shape the institutional museum experience. I’ve tried to create my own interpretation of these display devices to combine them with my works, adding elements like mirrors and hanging supports, which offer new viewpoints and alternate perspectives. For me this aesthetic, the accessibility, how-they-are-made and their apparent neutrality are full of embedded intentions and traces of power relations. I’m interested in digging them out.

Is there a logic behind the selection of imagery for the show? I ask because selection within the archive is often political, often ridden with blatant exclusions and known to generate ghosts. Are we looking at ghosts?

I use the exhibition as a medium, both as a context that guides my research and the creation of works as a documentation of this process. It is always an unknown process, I can’t decide what I encounter, and therefore, the selection of the works becomes very intuitive and, hence, uncertain. But of course, decisions are always made, so the ghosts arrive with them. There isn’t any exhibition, archive, or museum that is not haunted by ghosts, it’s all about one’s intentions and a certain awareness, I think. So maybe there is an attempt to deconstruct these elements that form systems of knowledge that often never rest in the process, revealing many things that are often forgotten.

Another aspect is the non-linearity in temporal perception when image and text collide, which is something that interests me a lot. I’m interested in the trickery or a moment of confusion these objects create in the viewer. I find this interesting tension when I create a book or page painting; they become weird, unfamiliar creatures. It also makes the medium of painting a more active subject for me, providing possibilities also to the viewer and bringing the image and text into an interesting proximity absent otherwise in conventional readings.

When we look at the image, our eyes start to move freely, and there’s not necessarily a line to be followed. Originally, the book paintings were made to be touched and held, they were exactly the weight of the book that they represent, but because this is a museum, it’s not allowed.

Layered Hills send off Glimmering Light, oil on canvas, 18 x 09 cm, 2024, in the collection of Saastamoinen Foundation

Layered Hills send off Glimmering Light (detail), oil on canvas, 18 x 09 cm, 2024, in the collection of Saastamoinen Foundation

The show, in a way, culminates in this interesting last piece where all your concerns and all approaches in terms of material and form are condensed into one piece, which again is suspended in a clear in-between, open to infinite possibilities, maybe I’m reading too much into it. Could you help here?

I would say this is the only piece that I couldn’t really wrap my mind around, but it was originally conceived as two separate works as foldable paintings that could form when combined, a bag-like structure, a container of sorts. It is also an attempt to break away from the traditional square painting that the viewer is often familiar with, thinking about structure and suggestion of functionality as objects for paintings. They have the same images from the screens, a sort citation and reference. Eventually, I attach them together with the existing shelf structure, by adding mirrors and chains. The surreal appearance that this piece reveals, in combination with all the materials, communicates to me a certain power that I don’t fully understand, but I decided to go with it and display it anyway. I see it as the beginning of something, it’s exciting.

Exhibition view Layered Hills send off Glimmering Light at Helsinki Art Museum, July 6 – September 1, 2014