Larissa Sansour, As If No Misfortune Had Occurred in the Night, 2022. Photo: Tuomas Uusheimo / Amos Rex

Rania Atef is a multi-disciplinary artist, cultural practitioner, mother of two and one of “Kohllective” members. She explores domesticity, authority, care, maternal/reproductive and labor discourses on both individual and collective levels.

Together, through their dynamic collaboration, Sansour and Lind invite the audience to be part of the dialogue they have created in their work. The combination of science fiction and existing narratives in their work pushes the boundaries of the audience’s imagination about national identity, loss, memory and trauma. Leaving the space for a critical discourse and thoughtful reflection.

I came to them with so many questions and thoughts especially when talking in these hard times when Palestine (the common protagonist in most of their films) is facing a genocide by the settler-colonial state of Israel. And their flow in the conversation added layers and layers and more questions. I hope to present a comprehensive understanding of their work and their current exhibition in the Amos Rex Museum in Helsinki with this condensed interview.

Rania: Thank you for sharing the films with me. It was my first time seeing them all. So I started watching the earliest to the latest. I have to say that I was fully impressed and overwhelmed- They hijacked my mind! So I will start with what I find common in most of the films, the idea of the narrative between the past and future where I don’t find the present. And “In Vitro”, I remember a line that says “The present barely exists”. And, I want to start from this point: why did you choose to dilute the present in your films?

Søren: Well, the absent present is a recurring theme in everything that we ever did in the past 15 years, this suspension - in the case of Palestine - between past and future. Even all the way back to “A Space Exodus” (2009), this idea introduced an ambition to rearrange and reshuffle the future so that it doesn’t mirror the present. Because, as you mentioned, the present barely exists.

So Palestine being temporarily suspended is the basis for how we conceptualize things between the catastrophes of the past, the Nakba, and everything else, and the ambitions for a state that seems to constantly move further and further into the future. And that means that the present remains sort of an unsettled purgatory.

But it’s all about getting to tomorrow. Or commemorating the past. And that’s what “In Vitro” (2019) is about. Do we mirror the past onto the future? Do we forge the future in the image of the past? Or do we erase it and let the past take the present with it? Let’s have a clean slate and completely renegotiate everything. So it’s this suspension between the past and the future that eventually annihilates the present.

Larissa: I also think part of it was trying to understand what the Palestinian psyche or even identity would be like if you remove the present, because the present is only defined as navigating checkpoints or the political situation, hoping for a better future. And while we’re talking about the future, Palestine is being slowly stolen. There are more land grabs, and the idea of a viable Palestinian state is becoming more and more obscure. We’re also understanding that Palestinian identity has become very synonymous with struggle, an identity that defines itself as being in permanent crisis. It’s impossible to think of the Palestinian identity without thinking of trauma. Basically, the Palestinian identity is trauma.

So this presence, we try to also define it in various ways. And “In Vitro” introduces a present rejected by the previous generation because their present unfolds in an underground reality. The younger generation, represented by Alia, is resentful of the fact that the previous generation thinks that her present is meaningless or even not real. Her present is nothing more than a state of waiting until they re-inhabit the earth. And that’s how Palestine feels. The projection of a future is all that really matters.

Still from Larissa Sansour & Søren Lind’s video work In Vitro, 2019. Courtesy of Larissa Sansour & Søren Lind

Still from Larissa Sansour & Søren Lind’s video work In Vitro, 2019. Courtesy of Larissa Sansour & Søren Lind

In response to what you mentioned about the present, can I say that you found in sci-fi a way out of the harsh and heavy moments of the present?

Larissa: I think that’s why we started using sci-fi, as it allows us to delve into psyche and trauma in ways fact-based commentary cannot, seeing as it has the ability to go beyond surface-level descriptions to explore deeper psychological and cultural implications. By creating a parallel universe, sci-fi opens a space to engage with present-day politics on new, layered terms, distancing itself from restrictive factuality.

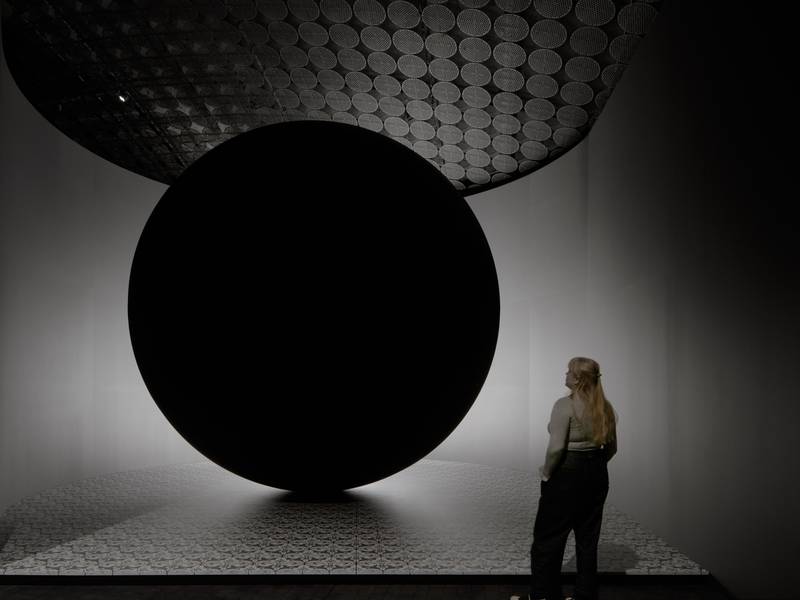

In the film, Alia interacts with a CGI sphere, a symbol representing a realm where she negotiates her traumas and confusion, which makes her sick. When representing Denmark at the 2019 Venice Biennale, we transformed this digital sphere into a physical, looming structure - “Monument for Lost Time” (2019). This object symbolized a rupture in time, highlighting how linear chronology fails to capture the Palestinian experience, especially following the 1948 creation of Israel, which cast Palestinians as mythological beings detached from real-time.

This sci-fi framework enables an exploration of Palestinians’ existence in a parallel universe, addressing complex themes like void and loss. We sought to create iconography that could resonate with the idea of nothingness, reflecting how trauma disrupts and redefines time and memory.

I believe there are many challenges and complexities when talking about Palestine, how do you think you deal with the challenges of presenting work from what some would perceive as a biased perspective?

Larissa: I am originally a painter and sculptor, I shifted to documentary filmmaking after witnessing the 2002 siege of Bethlehem, my hometown, while living in New York. When Israeli forces locked down the city, including the house where my sister and mother lived at the time, I felt compelled to document our lives as an assertion of existence amidst the fear of cultural erasure. It seemed that the evidence of our history could be erased, as has happened to other Palestinian places that are now part of Israel. Filming myself and my family became a way to say: “We exist; we did exist.”

Navigating Western perceptions as a Palestinian filmmaker has been challenging. Often, any portrayal of Palestine is seen as biased, assuming the Israeli narrative is the only objective truth. To counter this, I began using sci-fi, allowing me to kind of have my own universe, inviting people to engage. I want the Palestinian voice to have the same tools as any other voice.

I’m not sure if I answered your question directly, but it was part of the reasoning of how you navigate all the problems of showing Palestinian work and how you create interest rather than just make people feel sorry or scared.

Søren: In the beginning, we were loud about presenting a direct critique of occupation, amplifying real issues into a sci-fi narrative to expose the assault more clearly. Addressing walls, mobility issues, and the daily constraints of life under occupation. From 2015 onward, beginning with “In the Future They Ate from the Finest Porcelain (2016)”, we explored new lines of collaborative directions. This was our first experience with dialogue, and the shift led us to a more discursive, layered approach. Instead of straightforward protest and agitation, we introduced ambiguity, casting doubt on the narrator’s intentions, mental health, and even the nature of her interactions. Is she speaking to an interrogator, a therapist, or simply reflecting? This blurring raises questions about her reality and memory.

“In Vitro” presents a dialogue between two generations, one born in exile and the other forced into it, confronting differing perspectives on the past and future without taking sides. Similarly, “The Opera” provides a historical account of trauma without bias, while “Familiar Phantoms” (2023) fictionalized memory’s unreliability through Larissa’s family history. My outsider perspective has required careful consideration of how to engage with a narrative that wasn’t originally mine.

Still from Larissa Sansour & Søren Lind’s video work: In the Future They Ate from the Finest Porcelain, 2016. Courtesy of Larissa Sansour & Søren Lind

You also mentioned the “Familiar Phantoms” film, which I think is re-visiting for the documentaries once again. When I tracked your work, you started with documentaries and then a long period of fiction and sci-fi and then you landed again on documentaries. So I’m curious to know how this worked for you both, and why this shift now?

Larissa: I don’t really know. In the three films prior to Familiar Phantoms, we had been preoccupied with memory, specifically inherited memory and trauma and how to make a utopian society if our trauma gets erased. Should we attempt to erase all traumas or not?

Gradually I collected a lot of stories from my own childhood and family history, with the help of my brother who interviewed family members. And we found it interesting how collective memory changes from individual memory. So that became an aspect of our discussion, the blurry line between individual, collective and state memory. But I never wanted Familiar Phantoms to be an autobiography. It was intended as an investigation into the workings of memory.

Søren: Yes, “Familiar Phantoms” emerged as a film we were unknowingly crafting over the years. We accumulated various stories in a file and fictionalized some for other projects along the way. A voiceover in the film reflects on this process. She tells about once writing a family story out as a scene for a film, changing it along the way, and the changed version of the story soon replaced the real one in her memory. This highlights how fiction can replace reality. As these stories - from Larissa and her brother - formed the backbone of the narrative, they began to shape the film’s essence.

I transformed these intimate stories into a screenplay. This process involved further fictionalization, with Larissa often reminding me that I’m getting events all mixed up and blending different stories together. Ultimately, the script became a collaborative act of memory alteration, merging truth and fiction in a way that deepened our exploration of memory’s complexities.

Maybe this moves us to the exhibition itself. How do you feel now when you look at all these films together? Because when you do it one by one, you have a separate feeling and different circumstances for every artwork. But when you put them together, they form a very strong narrative - of course for the audience who receive the work. But for you as art makers, how do you receive this when you see the whole thing beside each other, especially now?

Larissa: A very nice question, because it does have a completely different effect when you see a lot of the works together, especially in a space like Amos Rex. The team there did an amazing job at installing the work. You really couldn’t be in better hands. And it’s a huge space. Each piece gets a lot of space and presence, and that accentuates the statement of each work to a point where it cannot be ignored, just as the overall show gives the impression of a continuous exploration of themes. It’s not just a single film that somebody did on a whim. There is a loud statement right there in the heart of Helsinki, and it’s clearly about Palestine. I don’t feel anybody could come to the show and feel that this is propaganda. There’s so much to explore that I’m hoping that people leave the museum thinking that they have just gotten overwhelmed by the Palestinian issue and almost knee-deep into it that they cannot dismiss it anymore.

Søren: What is satisfying about the show is to go back to the earlier works. I sat down and watched “In the Future They Ate From the Finest Porcelain” for the first time in years. And to understand how that film sentence by sentence reflects the tragedy unfolding right now was quite moving, even taking me aback that this was written as fiction because it no longer looked like fiction. But that fact alone underlines the cyclicality of violence throughout the past many decades. Whatever anyone wrote about or made a film about decades ago is repeated again and again.

The trauma of losing a child or sister is starkly evident in contemporary tragedies. Experiencing the works at Amos Rex, especially with the opera projected on a 13-meter screen, is incredibly engaging. The soprano’s presence is striking at such a large scale, and the sound system fills the entire space. It’s quite moving.

Larissa Sansour, In the Future They Ate From the Finest Porcelain, 2016. Courtesy of Larissa Sansour & Søren Lind

Larissa: Reflecting on what Søren said, our opera piece from 2022 resonates deeply in the current context, given the situation in Gaza. It’s fascinating how films are interpreted differently depending on the context, gaining new meanings over time, but that’s maybe what’s wonderful about works of art, how they can interact throughout time and how they acquire these different interpretations as well.

Speaking about the back and forth and this conversation between both of you, I can see that it is a very collaborative process and it is full of details, but I am curious to know more about how do you manage working together?

Larissa: We conceptualize together. So we decide that this is the kind of work we need to do and agree on the direction we need to take in the film, and there are always threads from previous works being explored further. So for example, if there are things that didn’t work for one film, we feel that there is still a theme that we wanted to explore.

But it takes a long time. The process is quite meticulous, and as a result there’s often a big gap between what we set out to and what the final result is. The more you sleep on it, the more it changes.

So many drafts of the scripts are written. Usually Soren goes away, actually leaves London, to write and concentrate. And I do visuals, and my visuals are also kind of informed by the content. So I kind of co-author the script, but visually.

Søren: I often start by thinking that we share an understanding of the new project. We both sign off on the notes, and I go turn those into a dialogue or a monologue or whatever. And then Larissa suddenly says: "By the way, can you fit in a big black ball?” I then ask her what that means, what’s the role of this new object, and she replies that she has no idea, so that’s for me to figure out.

But this kind of disruption always makes the work stronger. Now we’re so used to this kind of process that whenever we have a script that feels a bit too straight, I tell Larissa that it’s probably missing a big black ball. And then she goes and comes back with something. How about lemons this time?

Larissa: I think that’s the balance that we’re constantly trying to find. What is it that the text is not yet hitting on? And instead of relying solely on the text, we introduce a visual element that enhances the narrative and transforms it. I love that art is a malleable discipline; combining sound, visuals, and text, allowing us to meet halfway and make them work together.

Larissa Sansour, Monument for Lost Time, 2019. Photo: Tuomas Uusheimo / Amos Rex

And how does it work when you get to the practical aspect of directing the films?

Søren: We have different roles on set. For example, I don’t speak Arabic, so Larissa is in charge of language delivery and also always deeply involved in the translation of my English script to Arabic.

Larissa: Yes, translating Søren’s text into Arabic is very hard because we don’t really have a sci-fi language in Arabic. So I feel like I’m not only creating these works, but I’m also creating a new language, which is very bizarre. “In Vitro” Arabic is quite out there, and the task is how to normalize such a language. In English it works fine because of all the sci-fi films being produced, but not in Arabic. In the opera, the lyrics alternate between classical and colloquial Arabic. Part of it was based on a folkloric Palestinian song, so we had to make up new words to fit that song. So some phrases didn’t really make sense, but you know how it is in Arabic, where the folkloric songs are not just a spoken language. There’s a lot of back and forth when it comes to language, because you could easily feel that it’s just an English version translated into Arabic. It takes great effort to make it appear as not just a translated work, you have to own it and make it work in Arabic.

Yes I want to point out that there is so much effort in this process, because we don’t have either the language or the visuals of Arabic Sci-fi, but at the same time perhaps it helps in the sense of originality of work. Not only about language, but for the sound design, the costumes, every single detail leaves you with this sense of the mix between traditional and sci-fi. So how do you work on these details?

Larissa: In the opera film, we had a composer and a sound engineer. And then we also had a costume designer. The composer is from Lebanon, and I contacted him because I was trying so hard to find an Arabic composer who works with opera. I wanted to combine Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder with Masha’al - Palestinian folklore song. And I know that it’s very hard to combine them, but I want to take them to a completely new level of interaction with one another. And luckily, the composer was as crazy as us and got very excited about it.

It took us nine months to just work on the music before we even started filming. That was during lockdown. So we did everything over Zoom, which was really crazy.

And the costumes are by an amazing young costume designer who is an expert on Palestinian folklore. He knows all the details. But he also likes to just completely subvert these forms and create crazy versions based on folklore. It was a perfect match. And then on the shoot, we worked with our regular sound designer.

There are a lot of things you might not think of, like adding Foley, little ripples of water, footsteps, this kind of stuff. Our sound designer adds textures and themes, often sourced from the composer’s stems.

Søren: “In Vitro” has this big rumbly drone as a track that runs through the film, and that actually stems from the soundtrack composed for the big physical sphere we made. It has its own 25 minute soundtrack. Very deep, low-frequency stuff that almost hits you physically rather than just through your ears.

I want to go back to the exhibition arrangement and how it is planned. The last two works that the viewer sees are “Nation State” and “Space Exodus”. Did you intentionally mean something with placing those two at the end of going out of the exhibition? I think it’s very tense in “ In Vitro” or the “Opera”, then the black sphere -which you choose to get out of the film in particular- and then you end with “ Space Exodus” which somehow has a humorous sense and carries a moment of hope.

Søren: We had a very good curator, Terhi Tuomi. She has an architectural background. And because she has that sense of space, she becomes very good and skilled at placing works in unexpected ways. It was her vision to place the two newest works up front, loud and big as centrepieces. “In Vitro” and the sphere gets one part of the space, and the opera and the big pool with tree trunks hanging gets the other main part. And from that point onwards, it becomes sort of a chronology in reverse, ending with our first sci-fi work, “A Space Exodus (2009)”. That piece is sitting in a small box that mimics an old 50s-style television at the end of a long corridor. So you almost have this David Lynch-style horror walk down to this odd screen standing at the very end, an unexpected full stop rounding off the entire exhibition.