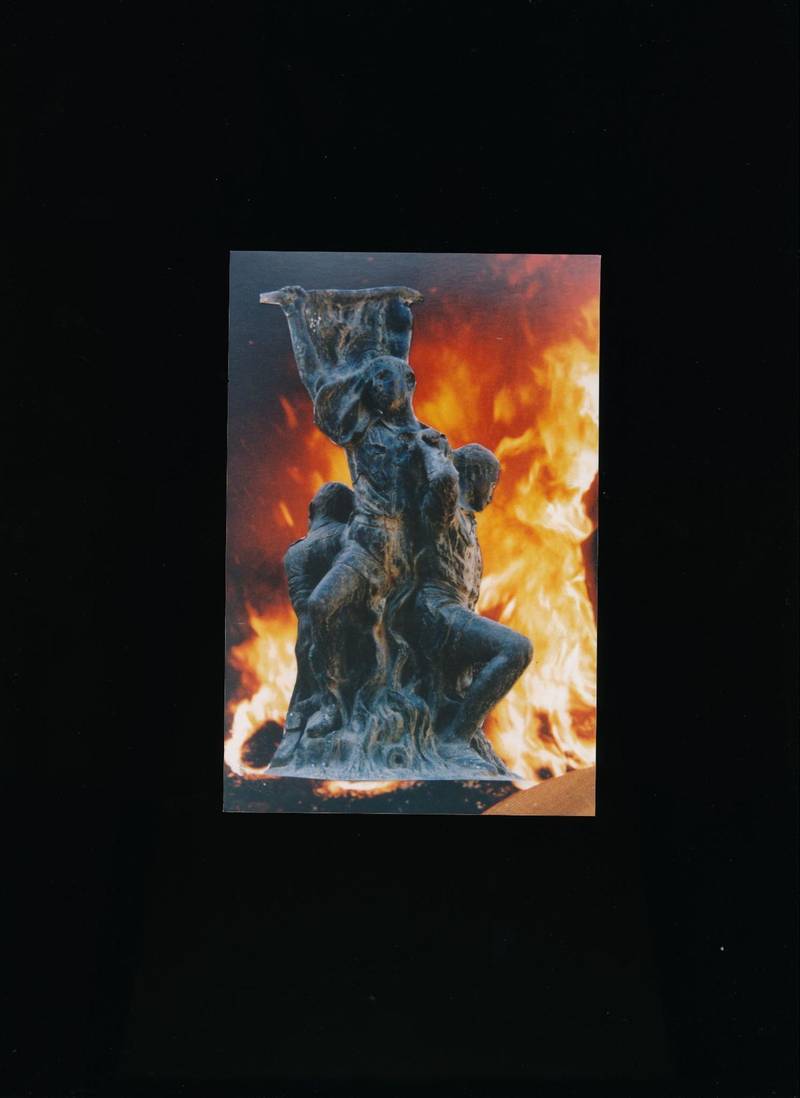

Cries of Inanna, Êvar Hussayni, mixed media book, 2024

Êvar’s multi-disciplinary practice focuses on Kurdish genealogies, colonial violence in archives and their relationship with the trajectory of Kurdish identities and feminisms. In her analysis of archives, she investigates the psychological impact of the archived material; what role does archiving play in shaping freedom - specifically that of occupied people and lands.

I.

2002 was a defining year for me. I was nine years old. It was the year I internalised that Kurdish women die no other way than at the hands of the patriarchy. My own death too. I had accepted that eventually, I would one day be killed. I had already lived the majority of my weekends in the backdrop of demonstrations and protests in Stockholm against the occupation of Kurdistan, watching adults scream for the freedom of themselves and of Abdullah Öcalan, the co-founder of the Kurdistan’s Workers Party (PKK) who was abducted in 1999, drilling into me that berxwedana jiyanê—revolution is life. Of course, at the time, there was only so much I understood. I understood that I was Kurdish. I understood that we “don’t have a country". I understood that we wanted freedom and had to fight for it. I understood that revolution was life. But I did not understand why.

Earlier that same year, news broke across Sweden about a Kurdish woman who was the victim of an honour killing. Her name was Fadime Şahindal. She had loved a non-Kurdish man, and her family did not approve. I remember this story being on the news for a long time. It was my first time seeing Swedish media speak about or mention Kurds; usually, it was Kurdish-speaking TV channels or Al Jazeera that covered our stories. That used the term: Kurdish. I would go to school, and my classmates would ask me if the same thing could happen to me. I have a vague memory of answering “no”, with a strange feeling of uncertainty about whether my answer was true. “Could this happen to you?” was also tinged, less with the upward inflection of a question, and more with the emphatic declension of certainty: this would happen to you. I was gendered and racialised as a nine-year-old; by nine-year-olds. For months, Fadime’s story was discussed through the lens of otherness; manufacturing fear of immigrants which had been ignited by the events of 9/11 just a few months earlier. I had accepted that Fadime had been killed by her own father, but there was only so much I understood. I understood that she was Kurdish and that her family had left Kurdistan because of the occupation, just like mine. I understood that her family preferred her death over allowing a Kurdish woman to love a non-Kurdish man. But I never understood why.

Later that year, Fariborz Kamkari released a film called Black Tape: A Tehran Video Diary. It was about a girl named Goli, who was kidnapped at 9 years old during the 1979 Kurdish uprisings in Iran, by an Iranian man called Parviz who at the time was an army commander, forcing her to become his sex slave and later his wife. The film, which has been banned in Iran, follows the abuse that Goli endures in her ‘marriage’ ten years later, through diary-like footage shot by Goli on a camcorder she received for her 18th birthday. The first time I watched this film was at my cousin’s house. I remember watching Goli rage against her imprisonment and her small acts of rebellion, such as smoking in secret when she became pregnant, learning English without her abuser’s knowledge, and searching for her family members whenever her abuser left the house. I remember the many moments her abuser taunted her for being Kurdish, proudly relishing his part in the violence inflicted on Kurds. I had accepted that Goli had been captured by an Iranian man, whom I understood to be our occupier, but there was only so much I understood. I understood that she was Kurdish. I understood that her family was part of the fight against the colonial violence inflicted by Iran, just like mine in Rojavâ. I understood that she faced constant abuse and had no freedom. But I never understood why.

2002 was a defining year for me as a nine-year-old. It was the year I internalised that my death would be at the hands of either my own family, my future husband, or whoever imprisoned Öcalan.

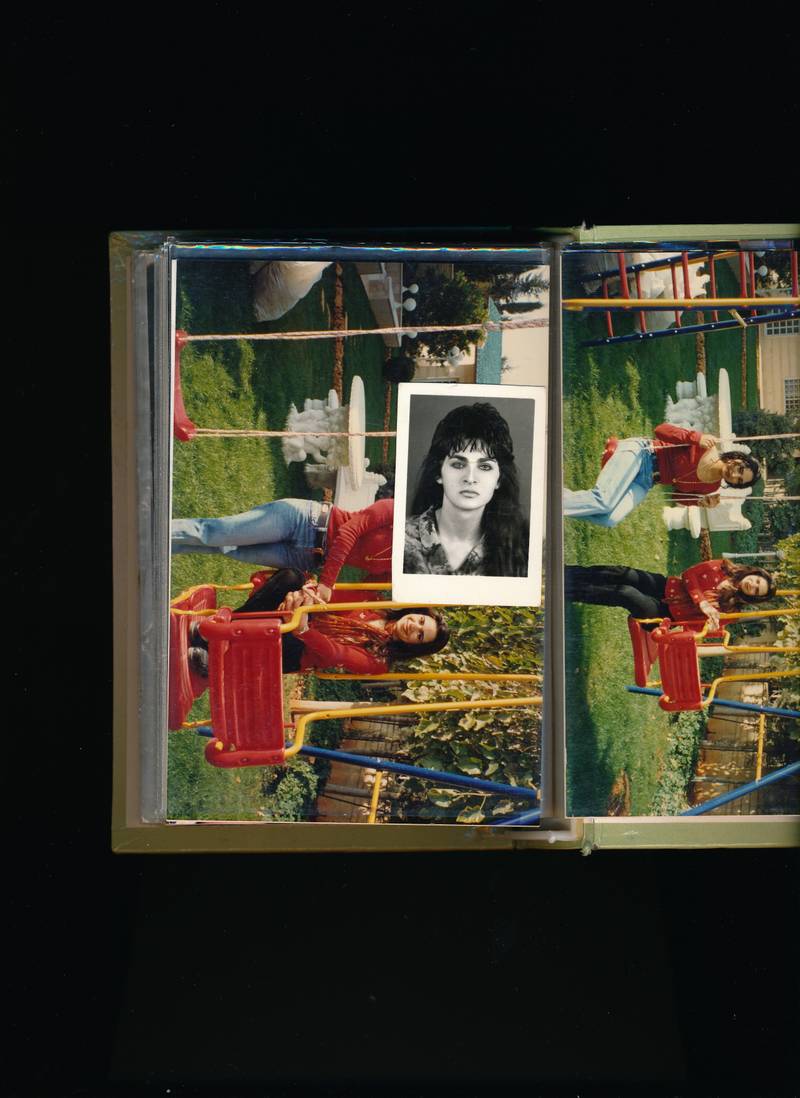

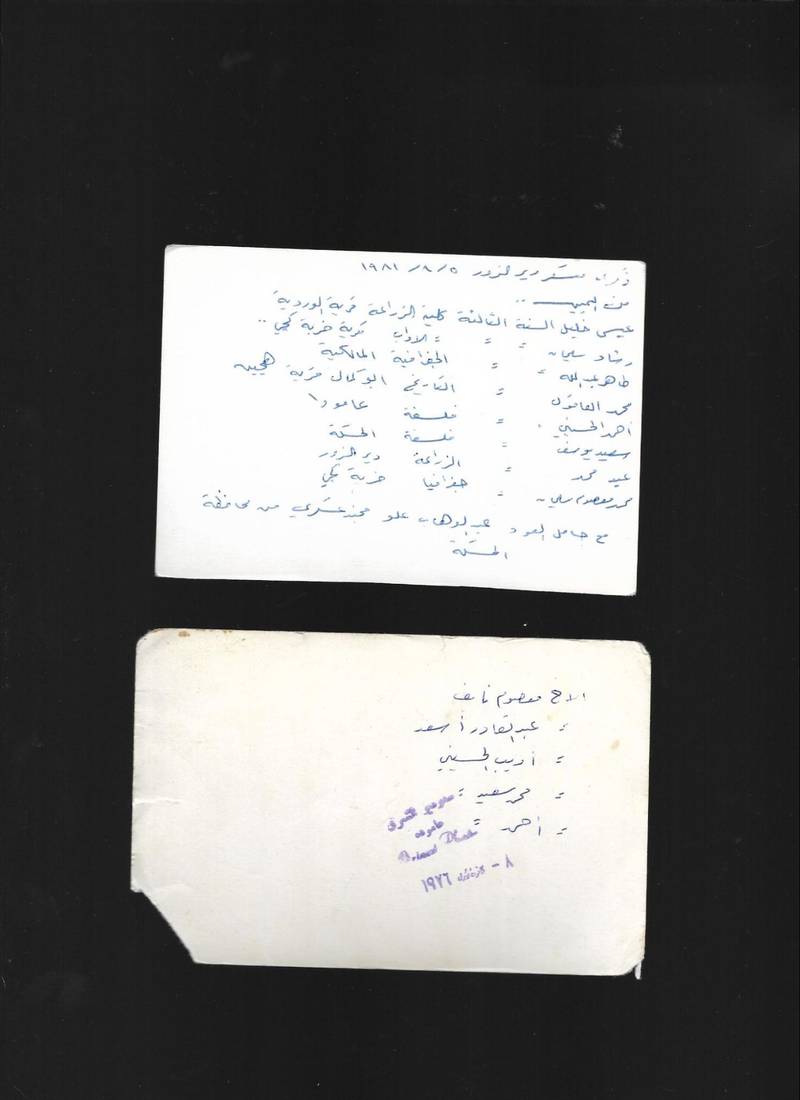

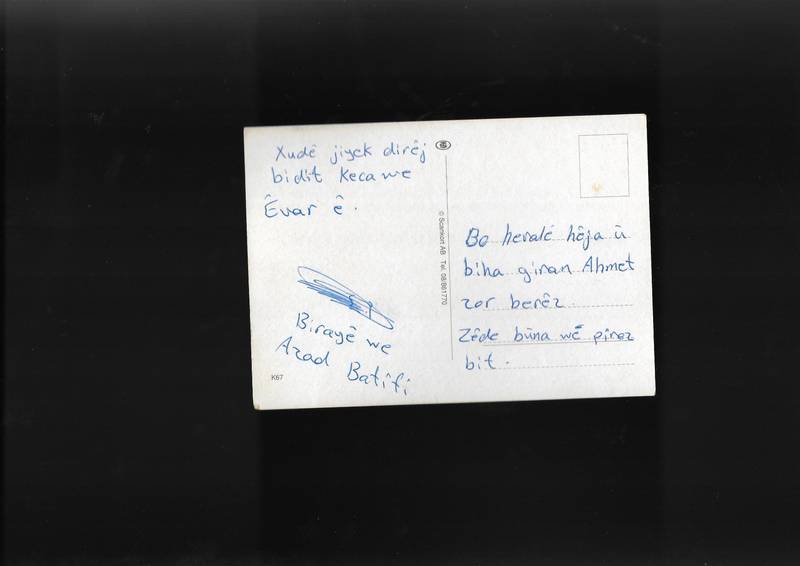

Cries of Inanna, Êvar Hussayni, mixed media book, 2024

Cries of Inanna, Êvar Hussayni, mixed media book, 2024

II.

My acceptance of my violent death informed much of my identity. Death became something that I associated with being Kurdish and being a woman - the witnessing and the encountering of these moments, and many moments after, came to form my understanding of a binary and heteronormative patriarchal system that I grew to resent and ultimately rebel against throughout my teens. It wasn’t until my mid-twenties when I was introduced to the language of archives, that I began to question how I/we got to this point.

The archive serves as the foundation of what shapes our memory. For definition’s sake, archiving involves collecting, preserving, and organising a variety of documents and artefacts to record and interpret history. Memory, in this sense, refers to the individual and collective remembrance of the archived events. Together, archiving and memory determine how societies understand and relate to their past, influencing present and future identities. The impact of the archive is immense, making archiving a tool for shaping collective memory and our many identities. The struggle is that nation-states, their governments, and their capitalist institutionalisation of the archive selectively document history to legitimise their perspectives, promote and reinforce dominant narratives, while deliberately omitting colonised voices and silencing others. This has rendered the archive an inaccessible place, despite the fact that in one way or another, we are all in it.

In Archives and Justice: A South African Perspective (2007), Verne Harris writes, “Archives are about power. They are about accountability. They are about memory. And they are about society’s choices about what to remember and what to forget”. Harris emphasises how archives can both suppress and illuminate truths, yet what triumphs are inauthentic archives where historical records are selectively curated to support prevailing power structures, systematically erasing authentic histories of resistance, collective experiences of violence, and alternative ideologies. Nation-states determine what is deemed necessary or dangerous knowledge for their citizens by controlling information and categorising ideas based on perceived social stability and security. Despite access to vast amounts of information, this biased approach distances us from felt truths, as historical records are skewed to align with state-approved narratives, often prioritising certain documents, stories, or artefacts over others, thus creating an “official” memory that aligns with homogenous societal values or institutional priorities.

During Saddam Hussein’s reign in Iraq, Kurdish media outlets were restricted or censored, limiting the coverage of Kurdish perspectives on events such as the Anfal campaign, where the Iraqi government carried out mass killings against Kurds with chemical attacks. State-controlled media in Iraq predominantly showcased narratives that justified government actions while silencing reports of atrocities committed against Kurdish civilians. The strangulation of truth in the archive is a primordial violence. The intersection of nation-states, memory and archival practice reveals that archives do more than store information - they actively shape individual and societal narratives of history, cementing hierarchy and inequality, which ultimately influences future generations’ perspectives on history. They determine which lives are memorable, notable, grievable.

III.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement was a 1916 treaty between Britain and France that divided Ottoman-controlled lands in West Asia into British and French spheres of influence, disregarding ethnic groups like the Kurds (amongst others) and leading to the division of Kurdistan across new borders of Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and Syria, with no provision for Kurdish sovereignty. The introduction of these borders ignited a process in each respective country to construct a hegemonic and homogenous society that would position each of their Arab, Turkish and Iranian identities as ancient, timeless and all-encompassing, and resulting in the calculated erasure of other ethnic minorities. This constrained any opportunity for Kurdish people to develop and exercise their cultural rights, instead scattering and isolating Kurdish identity. Policies introduced by four respective governments criminalised Kurdish identity through prohibition on the use of their language, bans on social and cultural traditions such as music, literature, Kurdish names, and forced assimilation by relocating Kurds to non-Kurdish areas of the newly bordered countries. In A Modern History of the Kurds, David McDowall (1996) dryly notes “all reference to Kurdistan being excised from official materials, and Turkish place names began to replace Kurdish ones”.

Actively erasing or censoring Kurdish heritage to prevent unity and reduce autonomy movements was a paramount step in ensuring true eradication and ethnic cleansing. Uprisings and resistances of Kurdish communities only prompted occupying states to resort to greater violences.

In The Wretched of the Earth (1963), psychiatrist and political philosopher Frantz Fanon investigates the premeditated and deliberate ways in which the ‘coloniser’ represses the ‘native’: “Colonialism is not satisfied merely with holding a people in its grip and emptying the natives’ brain of all form and content. By a kind of perverted logic, it turns to the best of the oppressed people, and distorts, disfigures and destroys it”. By ‘distort’, ‘disfigure’ and ‘destroy’, Fanon seeks to articulate the psycho-affective methods that colonialists implement to assert their superiority. The prioritisation of specific national identities led to the erasure of others, which also reflected in how histories were documented and archived. Actively erasing or censoring Kurdish heritage to prevent unity and reduce autonomy movements was a paramount step in ensuring true eradication and ethnic cleansing. Uprisings and resistances of Kurdish communities only prompted occupying states to resort to greater violences. The Dersim Rebellion of 1938 culminated in a massacre. Out of fear, many describe the aftermath as a “graveyard of silence”, with assimilation processes becoming more successful as Kurds were systematically silenced, leading many to identify less with their ethnicity to avoid violence. To get on with life. It was essentially illegal to be Kurdish. Distort. Disfigure. Destroy. Between the 1960s and 1970s, as guerrilla warfare strategies led by Che Guevara during the Cuban revolution and other tricontinental actors, marginalised groups began to mobilise with confidence. The distribution of Marxist journals across universities and bookshops inspired students to organise and form their own associations, and eventually, with the formation of the PKK in 1978 founded by Öcalan and Sakine Cansız, the Kurdish resistance movement emerged across all four borders. In response, ruling political parties (Kemalist, Ba’athist, Pahlavist) adopted increasingly authoritarian policies. This proved to be imprudent - all of those regimes were overthrown by violent wars and revolutions.

Counter-insurgency, in staking a claim to liberal warfare as Laleh Khalili notes, functions significantly through archival technologies of rule: documentation, categorisation and memorialisation form a triptych of power through the enclosure of knowledge, peoples and powers. Counter-insurgencies cast insurgent groups (colonised populations) as criminals or extremists, omitting and sublimating their political motivations for freedom and autonomy. These tactics influence what is recorded, preserved, or omitted in the archival record, allowing the state to legitimise its colonisation while marginalising and silencing opposition voices. Carefully executed guerilla tactics (In Rojavâ, Belfast, Gaza or Joburg) are portrayed as senseless violence; and organisations, whether the PKK or other, are designated and proscribed: terrorists.

On January 9th 2013, Cansız was assassinated in Paris. She was a significant figure in Kurdish and women’s rights movements, who committed her life to the struggle for Kurdish liberation. Cansız and two other Kurdish women activists, Fidan Doğan and Leyla Şaylemez, were shot in the head in an execution-style killing at the Kurdistan Information Centre. The heartbreak over their deaths spurred Kurdish communities globally into widespread protests, as it occurred amid peace talks between the Turkish government and the PKK. I am reminded here of my internalisation of how Kurdish women die; Öcalan was abducted, yet Cansiz, Doğan, and Şaylemez were killed by his abductor. It was a reminder that Kurdish identity, especially for women, poses an inherent trajectory. Their murder emphasised the silencing of women who challenge patriarchal and nationalist structures, reinforcing narratives of Kurdish women’s disposability and intensifying how Kurdish identity and resistance are inauthentically preserved and therefore incorrectly remembered.

IV.

Freedom, when defined, often conjures key terms such as “self-determination,” “unrestricted,” and “independent”. It is typically viewed as the absence of coercion and the ability to pursue one’s desires, yet it exists in constant tension with power dynamics. We witness this in the archive. The proximity of archives to freedom lies in their potential to preserve and amplify colonised narratives. By centering the voices of the oppressed and decentering traditional archival practices, we can engage more meaningfully with the lived experiences of those who resist, potentially implementing change as our memories conform to honest documentation and narration. Growing up amid protests and witnessing the continuous deaths of Kurds—especially the death of Kurdish women— meant that my understanding of identity and death became intertwined. It has now become a journey of untangling the two, instead pursuing the connection between memory and freedom.

In 2011, as the Arab Spring had spread throughout the region and settled in Syria, my grandparents and two cousins left Qamişlo, Rojavâ, for safety in Qoser, Bakur. Had they remained in Qamişlo, my cousins, not far from turning 18, would have been forcibly enlisted into the Syrian army to fight on behalf of Bashar al-Assad. A few years later, the war didn’t end, and my cousins left for America to begin their University studies. I had pleaded with my mum and aunts to bring my grandparents to Europe, driven by a desperation so intense that I never considered that perhaps my grandparents didn’t want to come. And they didn’t; they went back to Qamişlo. They wanted to die in the place where they were born, where their memories had been formed. And they did. That was their freedom.

How I come to imagine freedom in the context of the Kurdish struggle is my own form of un-learning. It is an un-learning that has left third-degree burns as I grieve the many magical possibilities I imagined as a child. Firstly, there was always an imagining of a return. Then there was an imagining of a gentler story - one not so filled with the relentless cycle of violence. One where Kurdish women weren’t killed by their own families, their husbands, or whoever it was that imprisoned Öcalan. The third was access. Being able to access my grandparents at any will.

At one point, it felt as though a solidarity movement could be ignited as people’s access to information developed, however, as the Western gaze fetishized and glamorised Kurdish women’s dedication to the struggle, it became apparent that the colonial archive’s neglect of authentic narration reduced them to subjects of constant death and demise.

In the last decade, there has been a rise in the documentation of Kurdish resistance, as mainstream media sought to highlight the role of Kurdish women in the fight against ISIS. At one point, it felt as though a solidarity movement could be ignited as people’s access to information developed, however, as the Western gaze fetishized and glamorised Kurdish women’s dedication to the struggle, it became apparent that the colonial archive’s neglect of authentic narration reduced them to subjects of constant death and demise. What was never questioned was how Kurdish women came to be at the forefront of the resistance movement — what historical moments had led to this point? This hope for solidarity also proved to be a fallacious fable that I grieved when the 2022 Iranian uprising exposed once again the coloniality that regional communities, academic institutions, and the art world had strived to conceal under the guise of capitalist-driven “Diversity and Inclusion” movements. Documenting and preserving traumatic memories in archives requires methodologies that prioritise sensitivity, accuracy, and respect for those involved. Archives dealing with trauma often include oral histories, survivor testimonies, photographs, and official documents - during the funeral of Jina Amini, her parents specifically asked that she be referred to by her Kurdish name, and never by her colonised name. The appropriate response would have been to honour the victim’s story. Why did she have a colonial name in the first place? Providing contextual framing helps educate those who may not have understood why Jina’s death ignited an uprising in the Kurdish region occupied by Iran. How easily one can become a subject, having no say in how they are remembered - a Kurdish woman named Jina. But even in death, Jina cannot rest as her liberated Kurdish self. Even in death, her colonial name persists in the archive. I am transported back to Black Tape: A Tehran Diary, where Goli ends the film with a monologue addressing her Kurdish name and identity: “My name is Galevije Salary. It has been years since I have spoken my language. Nobody has called me by my real name. I wanted to choose my own destiny […] There are girls who don’t speak in their own language. Girls who don’t live in their homelands. Even their history doesn’t belong to them”.

Cries of Inanna, Êvar Hussayni, mixed media book, 2024

Cries of Inanna, Êvar Hussayni, mixed media book, 2024

V.

Jineolojî, the science of women, developed by Öcalan and the Kurdish Women’s Movement is rooted in the abolitionist critique of patriarchy, capitalism, and traditional social sciences. Through decades of resistance and struggle, Jineolojî aims to develop alternatives to nation-states, knowledge production and understandings of the liberation of women as foundational to global freedom. It is through Jineolojî that I approach my relationship with the archive and my relationship with death. I navigate death with questions such as “Who gets to live?”, “Under what conditions do they get to live?”, “Who determines death?”, as I decipher whose life we are persuaded to consider valuable by the colonial answers to these questions, and reflect on a reality where Kurdish lives are continually contested. State-imposed erasure, forced assimilation, and targeted violence render Kurds as disposable under colonial logic, shaping collective Kurdish identity around survival and loss. Grappling with these questions through the archive, memory-making and methodologies that Jineolojî motivates me to apply becomes an act of preserving existence, reclaiming agency, and constructing an identity beyond disposability. It becomes an alternative knowledge transmission to facilitate solidarity building, with an approach to the archive as an emancipatory praxis.

Developing alternative knowledge and self-representation methods is crucial for the Kurdish struggle against colonisation and cultural erasure. It involves reframing narratives that have historically marginalised Kurdish voices within state-centric discourses. The alternative to this is treating the archive as alive to develop mnemonic frameworks that reflect the realities of Kurdish identity and resistance. In engaging with my memories through Jineolojî, shaped as they are by a mix of rage, grief and longing, I am conscious that this is an identity-making, a self-story telling that I try to ensure holds space for complex emotions while forging a narrative that is neither dictated by loss nor limited to our colonisation. It is, instead, an evolving testament to a Kurdishness that is intimately personal and profoundly collective, and continuously shaped by Kurdish women who remember, resist, and redefine themselves to exist outside of the colonial framework. In that way, too, it is ephemeral. It is perhaps my refusal to position my duty to the Kurdish struggle in the language of deservingness and instead, use the archive to politically educate myself and those around me on death, on life, on who falls in each category and why. It is creating new meanings, new references, and new memories for future generations - preserving and sharing unfiltered Kurdish history, cultural practices, and stories of resistance that have long been excluded from mainstream archives, with methods like oral storytelling, embodied archives, and community-based memory projects to resist the state’s distorted narratives, focusing instead on grassroots approaches to documenting life. Through Jineolojî and memory-making, alternative practices offer frameworks that emphasise Kurdish identity formation, providing alternatives to inherited trauma. It becomes an evolving testament and commitment to the struggle for freedom and self-determination.

Cries of Inanna, Êvar Hussayni, mixed media book, 2024

VI.

A habit of mine when travelling is to always try and find libraries, archival institutions or community centres that might store archives, to visit in the city that I am in. Wherever I go, I will find one. And the first thing I ask when I enter these spaces is, “What do you have on Kurdistan?”. In December 2023 I did this in Dubai. A newly opened library found itself on Alserkal Avenue with a focus on “global governance, foreign policy, neocolonialism, and culture”. My interest peaked when friends said that the library held plenty of political books. I did the usual - walked in, looked around, picked out a few titles to read, and then went up to the help desk to find all the titles related to Kurdistan. They had not a single one. A library, with thousands of books, focused on foreign policy and colonialism, had not a single title on Kurdistan.

I think of Cansız’s memoirs which were translated into English in 2019, 6 years after her death, and how fitting her revolutionary thoughts would be to this library, next to the writings of James Baldwin and Ghassan Kanafani. I think of Hevrîn Xelef who was murdered in 2019 by Turkish-backed Syrian Ahrar al-Sharqiya fighters - she founded the Foundation for Science and Free Thought in 2012. Their work would fit so well in collaboration with so many of these learning institutions, especially as conversations around collective practices are starting to flourish. I think of Nagihan Akarsel, a writer and co-editor of the magazine Jineologî, which focuses on the ideological concept of women’s individual liberation as a pre-condition for society’s liberation. She was assassinated in front of her home in Silêmanî in 2022 on the orders of Turkish intelligence - her writings would benefit so many of these libraries that seek to apply to their collection the concepts of struggle, revolution and freedom. I think of the responsibility that archivists and librarians hold of knowledge production and information circulation, but how obscured this can become by the conditions of the person doing the archiving, and how that library’s neglect of Kurdish narratives has reduced Kurdish identity, once again, as one to be erased.

Archives play a significant role in my pursuit of the connection between memory and freedom, in my pursuit for a more gentle truth, yet continuously the institutions that hold power over the archive ignore their responsibility in the way it shapes our memories and do so little to undo the hurt that the world endures under a capitalist system. How do I carry on with my research, my life-work, knowing that an anti-fascist life could be possible, one where, unlike Goli, Kurdish women can choose their own destiny, yet amidst multiple genocides and massacres a life as such feels so truly impossible? How do I envision liberation and freedom, when these definitions are something you and I have never even come to ever know and understand.

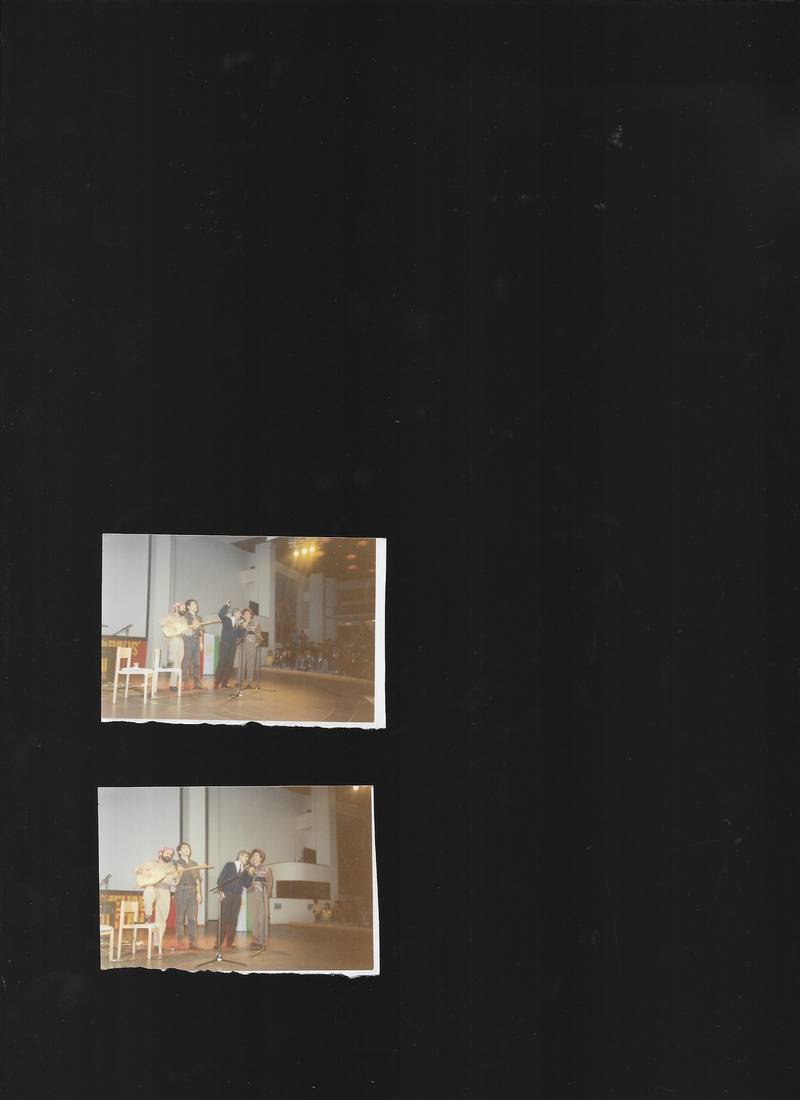

I remember not long after my visit to Dubai, I was delving into one of my uncle’s photo albums back in Stockholm. I found a photo of Pêsmerge playing volleyball in the Kurdish mountains from 1984. Pêsmerge translates to ‘Those Who Face Death’. He was in the picture. It quickly became my favourite picture I had found so far, because it wasn’t often that I discovered joy in the archive when I researched the Kurdish struggle. That’s when I understood that the entire archive is one of struggle, and that my life-work is to simply try and show the alternative that actually already exists. But how easy is it to showcase these alternatives when our imagination has been so criminalised and so destroyed by impossible violences? Can our imagination of freedom ever reach beyond a certain degree?

I must decipher who is free and who gets hurt in the process of reaching freedom. It is an important aporia to decipher as the resistance movement trickles down generations of Kurds, but the bodies are not travelling with the resistance. They are the ones who must die, and they are the ones whose bodies, if archived, are archived through a violent or reductive lens.

My process for understanding freedom becomes more complicated, so let’s return to those questions of who gets to live and who must die. Firstly, as an archivist, or as an artist whose work is dedicated to the archive, I must decipher who is free and who gets hurt in the process of reaching freedom. It is an important aporia to decipher as the resistance movement trickles down generations of Kurds, but the bodies are not travelling with the resistance. They are the ones who must die, and they are the ones whose bodies, if archived, are archived through a violent or reductive lens. I think about all of those who don’t get to be there when freedom is achieved, but who dedicated their whole life to trying to achieve it. I think about my uncle who wrote and sang Kurdish songs in a time when the Kurdish language was illegal to speak in Syria, and whose body has been missing since the year I was born, but whose lyrics I have memorised and will continue to sing. And then I look at the picture of my other uncle and his comrades, playing volleyball in the mountains of Kurdistan, their AK’s to the side of the court, and I think of our hyperfixation on martyrdom, and how we are complicit in making that the only narrative. Surely death is not the only narrative. So many also survived. So many are still fighting. And they experience joy. That can be archived too. Joy can be part of the collective memory too. They are here with us, recultivating and rebirthing the traditions, culture, language, names, music, art that are constantly attempted to be destroyed and erased. And as archivists, our responsibility becomes one with the resistance, where we ensure that our conditions do not infiltrate authentic information circulation, one where colonisation and hierarchy won’t find a home in the archive. One where the answer to “Who gets to live?” becomes “everyone”. One where we take accountability for what we choose to remember and what we choose to forget.