Illustration by Coireall Kent

Students for Palestine Finland is a national student-led movement dedicated to advocating for the implementation of academic boycott in higher education institutions as called for by the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement.

Nothing began on October 7th, 2023, in Palestine. The struggle existed long before that day. However, in the aftermath of Al-Aqsa Flood and the Zionist entity’s response—backed by its Western supporters—a wave of mobilisation and organising emerged. Led by organisers from the Finnish Palestinian community, this wave grew into a broader movement, bringing together people from diverse backgrounds. We are united by a shared determination to advance the goals Palestinians and their allies have pursued for decades. The Zionist stranglehold on the narrative surrounding Palestine is weakening. As public awareness grows, so does critical scrutiny. We are living through a global moment of anti-Zionist awakening—and we are determined to seize it.

As students in Helsinki, we have watched our peers worldwide push their universities to support the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) campaign and the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI). We have celebrated small victories and drawn inspiration from students who successfully pressured their institutions to adopt boycott measures—among the first in countries like Ireland, Norway, and Spain. At the same time, we watched in horror as police violently repressed student organisers in the US, Germany, Austria, and beyond. We were not surprised to learn that universities themselves had called the police—and that the most aggressively targeted students were overwhelmingly migrants and students of colour, including Palestinians.

In response, our universities—these bland bastions of neoliberalism—have called the police on us and used various tactics to silence and shut us down. They have taken all measures to avoid confronting the immorality of their ongoing financial entanglement with Israel, which includes investments and direct cooperation with Israeli institutions complicit in the escalating genocide.

Our actions—rooted in a shared understanding of the Zionist colony in Palestine as a manifestation of imperialism and capitalism—have been multifaceted and diverse. As students organising for Palestine in Helsinki, we have written open letters to university administrations, walked out of classes, organised and joined protests, and occupied campus spaces through encampments. We have created spaces for learning by hosting reading groups, lectures, and discussions on Israeli colonialism, apartheid, and genocide. We have dropped banners in university lobbies, gathered signatures for petitions, and launched initiatives demanding action from our universities and student unions.

In response, our universities—these bland bastions of neoliberalism—have called the police on us and used various tactics to silence and shut us down. They have taken all measures to avoid confronting the immorality of their ongoing financial entanglement with Israel, which includes investments and direct cooperation with Israeli institutions complicit in the escalating genocide.

This article is an attempt to contribute to the shared dream of supporting students who organise for Palestine—both similarly and differently—around the world. It is not simply a record of “what we have done,” though it includes some of that. Divided into three sections, the article is written by representatives from three institutions: the University of Helsinki, Uniarts, and Aalto University. Each section shares unique experiences, processes, and insights while also mapping a web of connections that have united our actions. We aim to reflect on how we have learnt from and supported each other, how our work fits within a vast global movement, and how we stand in solidarity with those resisting everywhere.

At the heart of our reflections is the belief that our work is made possible by the interconnectedness of global resistance. What we achieve today in Helsinki is built on the struggles of others worldwide. Through this article, we seek to strengthen that web by sharing what we know, how we know it, and offering provocations for what might come next.

Students joining the Labour Day protest in Helsinki, May 1, 2024. Photo by Satu Söderholm

University of Helsinki

Finland is not known for a strong tradition of radical student mobilisation. However, something shifted in September 2023 when students at the University of Helsinki occupied their university in protest against the neoliberal and racist policies proposed by the Orpo government. This wave of dissent grew rapidly, sparking student occupations across educational institutions from Helsinki to Rovaniemi. The growing “Students Against Cuts” (Opiskelijat Leikkauksia Vastaan) movement called on educational institutions to stand with their students, emphasising their roles and responsibilities as societal actors.

The austerity measures proposed by the alt-right neoliberal Orpo government threatened to further restrict access to higher education for low-income and international students. The refusal of most university leadership to defend students’ rights against these discriminatory policies fuelled a growing awareness of the neoliberal university as an adversary. Peaceful student protests were, at times, met with violent suppression—further exposing universities as active participants in state violence.

It is crucial to recognise the context in which our efforts to hold universities accountable for their complicity in genocide emerged—within the already established networks of the anti-austerity student movement. Despite the movement’s significant mobilising power, it struggled to effectively connect the fight against austerity with the urgent demand to end the extreme violence against Gaza and its institutional backing. This disconnect ultimately led Students for Palestine to break away from the already existing student movement against cuts.

Students for Palestine (SFP) not only critiqued the neoliberal university—its close ties to state bodies and lack of democracy—but also identified it as a key site of imperialist accumulation. Students highlighted the university’s role in facilitating the flow of value from the core to the peripheries, where the Zionist genocidal project is directly supported by governments and educational institutions. Adopting the BDS and PACBI boycott calls was an obvious first step.

While Students Against Cuts (OLV) initially sought support from university leadership—a strategy which, for some, was an unexpected failure –—SFP never entertained such illusions. The Finnish state’s longstanding support for the Zionist project, combined with a growing awareness of the neoliberal university as a state-aligned actor driven by economic interests, made it clear: our institution’s interests directly oppose Palestinian life. Situated within the broader imperialist system, the university was always going to be a site of struggle—and its structures, inherently against us.

Like with OLV, activity at the University of Helsinki also sparked and supported wider student mobilization. And unlike OLV, which was led by established leftist student organisations, SFP brought together people with fewer ties to existing student structures, fostering a more independent and radical approach.

Coming from a variety of political standpoints, simply calling for decolonisation, an end to genocide, or identifying our most obvious opponents was not enough to form a functional political core. What grounded our efforts was the longstanding work of movements like BDS, which provided us with concrete demands and a clear path to participate in the global academic and cultural boycott of Israeli institutions. Aligning with the BDS call gave us both legitimacy and clarity in our demands, challenging us to connect our institutional context and lived reality to the broader framework of boycotting, divesting, and sanctioning. In other words, we did not invent anything—we inherited an anti-colonial struggle that has lasted for over 76 years. This legacy, along with the BDS movement and global student mobilisations for Palestine, offered us a roadmap that we began to root in our local context.

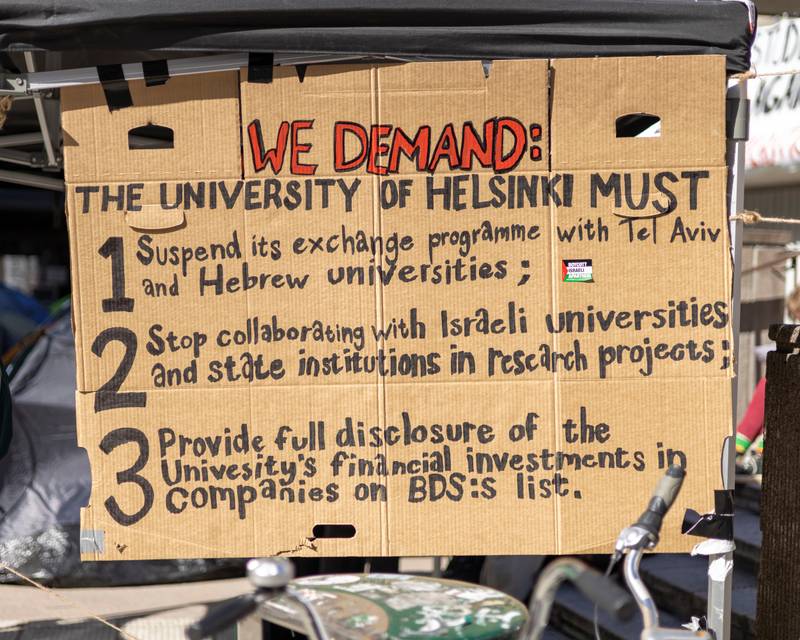

A sign at the Student encampment at the University of Helsinki, May 2024, Photo by Satu Söderholm

As we sought to criticise the systems supporting the Zionist project, we also faced the limitations of our own positionalities. We had to confront our place within the world system and our presence in the educational institutions of the imperial core—institutions that, whether we liked it or not, we were shaping simply by being part of them. Our inexperience with sustained political struggles, coupled with a long-standing trust in institutional structures that were now clearly against us, created a tension: we had mobilising power, but we struggled to build lasting political structures—such as forming coherent strategies capable of challenging these institutions over the long term.

For a while, the lack of a political analysis and formal strategies was offset by the sheer momentum of the movement and the overwhelming support from both local and global networks. With the guidance of BDS, we began to envision anti-Zionist action from within the imperial core. Our political goal was clear: to disrupt the flows of wealth and support from our institutions to the Zionist entity.

However, in our efforts to sustain and build a lasting student movement, we grappled with a deeper realisation—our daily lives in the imperial core are deeply intertwined with the genocide of Palestinians. We struggled with effectively and clearly connecting the dots between our conditions in Finland and the fight against Zionism.

There was much to learn, and in many ways, we had to start from scratch. Locally, we had few examples or predecessors to build upon. By the spring of 2024, we began to question familiar ways of organising. Flashy, adrenaline-driven, feel-good actions were no longer enough—along with mobilising people for demonstrations, we needed to commit to long-term political organising. This required us to decentre ourselves, a shift that challenged the dominant organising culture in Helsinki.

We also struggled with a superficial political culture that frequently overlooked the significance of deep-rooted political analysis and sustainable strategies. The activist trends of the 2020s, which favoured short-term mobilisation and reformist narratives, left us without the political continuity needed to build a lasting movement. Beyond the demands for BDS and a ceasefire, we were often ill-equipped to formulate a clear political core.

Our unpreparedness became especially clear during the six-week Gaza solidarity encampment, where the need for political clarity and effective organising was urgent. The challenges of “horizontal” organising—combined with unclear notions of solidarity—led to unequal distribution of responsibility, disempowered agency, and difficulty making strategic decisions. Our reliance on non-hierarchical structures, while well-intentioned, often hindered our ability to act decisively.

At times, we were internally divided on strategy. However, the “no-veto” structure and group autonomy allowed for multiple approaches when passions and perspectives differed. This sometimes led to unexpected results—such as launching the student union members’ initiative alongside the encampment—which ultimately strengthened both efforts, enhancing the initiative’s visibility and the encampment’s legitimacy. The political pressure of the encampment was combined with lobbying to finally make the university board discuss our demands. While the outcome of freezing exchange programmes was at best unsatisfactory, and while the encampment revealed the limitations of our organising methods, what was highlighted was the power of forging relationships across lines of societal status. Its open and communitarian nature—welcoming everyone who supported Palestine—became its greatest strength.

Inspired and empowered by the idea “once you start, people will come", the campus encampment was prepared by a very small team, but what reproduced, the encampment for weeks was the strength of people joining forces. Fuelled by the global “Student Intifada”, we succeeded in using the resources of the university against itself, and created a space ‘in but not of’ the university, as Fred Moten would describe. These experiences encouraged us to reflect on and challenge the individualistic and isolated organising culture that had previously defined our movement, a process which continues to this day. The ability to ask for and receive help, and to decentre personal egos proved essential in sustaining the movement and shaping its direction.

Student encampment for Palestine outside Porthania, University of Helsinki, May 2024, Photo by Satu Söderholm

Uniarts Helsinki

On 16th September 2024, after months of communicating through group chats—just names on screens—we finally gather in person at the Theatre Academy as Uniarts Students for Palestine. Together, we discuss formalising our activism to better distribute tasks and ensure the continuity and sustainability of our work. The group includes students from the three academies under Uniarts, each with different physical spaces and political cultures. Yet, we share a common challenge: the demanding pedagogy of 100% attendance required in most courses. This raises a pressing question: How do we carve out space for organising within an institution designed to keep us fragmented and overworked? How do we resist individualistic grinding and bring people together for collective action?

To anchor our efforts, we establish biweekly meetings—a space to plan new actions, distribute tasks, and welcome new members. One student, Anna Karima “AK” Wane, a recent graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts, wrote candidly in their master’s thesis about navigating the silencing of pro-Palestine activism at Uniarts. They recall an early incident when a group of students sent an open letter to the university demanding action toward an academic boycott. When the university failed to respond, we circulated the letter across all three academies and began collecting signatures. Shortly after, an email arrived from Uniarts Rector Kaarlo Hildén: “It is important not to use the university’s email lists for political activities.” He argued that the university should remain a neutral space where all students feel safe.

AK posed a critical question in their thesis: “Whose safety are we talking about? Who gets to feel safe?” They highlighted the hypocrisy of this so-called neutrality—especially since the same office had previously condemned Russia’s attacks on Ukraine in no uncertain terms. This double standard is not unique to Uniarts; it reflects a broader pattern across Helsinki’s universities and the Western academic world. At Uniarts, Ukrainian students were offered tuition waivers to continue studies disrupted by war, and Russian universities were swiftly cut off from academic cooperation. Yet, following October 7, 2023, as Israel escalated its assault on Gaza, no similar action was taken against Israel, nor was any support extended to Palestinian students.

Banners made by Uniarts students, hung in the Helsinki Academy of Fine Arts staircase.

Navigating the question—“Who gets to feel safe?”—has been central to our organising. After one of our biweekly meetings, some of us reflected on how the only time being in a Uniarts building feels meaningful is after these gatherings. After all the silencing and being unheard—while trying to remain arts students as a genocide unfolds—it now feels like the only relationship that makes sense with this institution is one of resistance.

But being moved to act is only half the work—the rest lies in the question: which actions? Where do we direct this force? What will actually work? How do we push the university to commit to an academic boycott? We have tried many things. And while the goal remains ahead, we have come further than we imagined when we began.

One strategy we developed in the summer of 2024 was submitting a membership initiative to our student union. A membership initiative is a tool of university democracy; in Finnish universities, all BA and MA students are part of the student union, which represents students’ voices. At Uniarts, an initiative can be submitted by five students and must be addressed by the Representative’s Council within two months. If approved, it proceeds to the student union board, and if passed there, its proposal can be enacted.

Palestinian activist, artist, and National Union of University Students in Finland board member Eugenie Touma van der Meulen used lobbying with board members to pave the way for the first initiative advocating an academic boycott of Israel. The strategy was quickly adopted at both Uniarts and Aalto University. After gathering 153 signatures from student union members, our initiative passed the Representative’s Council on September 4, 2024. This made the demands of PACBI and BDS the official stance of the Uniarts student community, obligating the student union to pressure the university to cut academic and financial ties with Israel.

The connection between meeting rooms across the globe and through time is not just symbolic—it is real, material, and built through hard work. Contacting past activists and documenting our work is essential.

On November 7, 2024, we formally presented these demands to the university administration at the Theatre Academy. The chair of our student union speaks first, explaining why TaiYo has finally committed to demanding an academic boycott. Two weeks earlier, they issued a statement supporting the academic and cultural boycott to pressure Israel into complying with international law—aligned with PACBI and BDS movements.

Then, it’s our turn. This is not the first time we’ve sat across from rectors and deans, explaining why the university must end its complicity in the genocide unfolding in Gaza. We ask the same questions: Why could they make a statement about Russia invading Ukraine but not about Israel invading Palestine? What will they do about their collaboration with Bezalel Academy of Arts in Jerusalem—a school that has proudly declared its Zionist affiliations and has directly participated in the genocide of Palestinians by sewing uniforms for IDF soldiers?

The connection between meeting rooms across the globe and through time is not just symbolic—it is real, material, and built through hard work. Contacting past activists and documenting our work is essential. Thanks to meticulous records kept by Students for Palestine at Helsinki University, along with our own, we enter this meeting prepared. We know the leadership’s tactics, the strategies they use to evade accountability, and the promises they have made before. Institutions repeat the same lines to exhaust students—but when we recognise their playbook, we can turn it into our strength.

One key strategy was preparing a “frequently asked questions” document to anticipate and neutralise common objections:

- Doesn’t an academic boycott limit academic freedom?

- How would joining the academic boycott affect Israeli students and staff at Uniarts?

- There are many problematic countries—why boycott Israel specifically?

By addressing these questions preemptively, we kept the conversation focused and principled. Leaning into the institution’s concerns allowed us to resist its evasions.

This strategy—leaning in to resist—was evident throughout the membership initiative process. By using university democratic tools, we demonstrated that we were not just a handful of activists but a substantial portion of the student body, staff, and alumni demanding an academic boycott. Yet, the process also raised questions: Why are students only taken seriously when speaking through the student union? Why does institutional legitimacy seem to be a prerequisite for our voices to matter—especially when addressing genocide? The slow bureaucratic process was frustrating, and the university expected us to be softer, more moderate, blaming us for “creating opposition.” Yet from our perspective, the university itself imposed this opposition, framing us as a threat. Through the membership initiative, we challenged that framing.

The opposition is not only between institutions and student activists—it also exists within our movement, manifesting in differing strategies. Should we focus on direct, visible actions or institutional processes? Should we shame the university publicly or appeal to its conscience? These approaches are not mutually exclusive—they reinforce each other. We use both the university’s tools and our own. Now, when the university tells us to use “established pathways,” we can say, “We have done that too.”

At Uniarts, banner drops, emails, walkouts, and persistent visibility for Palestine steadily shifted the university’s position leading up to the membership initiative. These actions prepared students, staff, and leadership to receive it. Now, with its passing, even more space exists for direct action to grow. The two strategies—pressure and process—work together.

There is much to resist at Uniarts, but the institution also provides resources—such as access to space—that we can mobilise. Our artistic skills are one of our greatest strengths. From graphic design to performance, from voice work to writing, these tools serve our activism. We are now working to share them with other groups organising in solidarity with Palestine.

Political Participation in the University, an event organised by Uniarts. During the event students rehung banners in the staircase that had previously been removed by the university. February 2024.

Aalto University

In the summer of 2024, we decided to formalise our campaign for an academic boycott at Aalto University by submitting a membership initiative to the student union, AYY. The initiative called for AYY to commit to the demands of BDS and PACBI, following the precedent set by the University of Helsinki Student Union (HYY), which passed a similar initiative in May of that year.

As a formal institution, AYY holds a legitimacy in the eyes of the university that our group of activists does not. Representing over 10,000 Aalto students, AYY has an established structure and influence. Its highest decision-making body, the Representative Council (RepCo), consists of 45 elected members from the student community. These council members are organised into electoral alliances based on academic disciplines and political affiliations, shaping the direction of student advocacy within the university.

According to AYY’s rules, we needed at least 30 student signatures for our initiative to be considered by RepCo. We saw this as an opportunity for direct outreach on campus, alongside promoting the initiative on social media. In the end, we gathered around 400 signatures before formally submitting it to the student union—far exceeding the requirement.

Once the initiative was delivered, some RepCo members who supported it suggested that certain references to BDS were “problematic” and that the initiative might gain broader support if it wasn’t explicitly tied to BDS. We rejected this suggestion outright, insisting on our original wording, which explicitly called on AYY to commit to the principles of BDS and PACBI. This moment underscored a key lesson: while engaging with opposition is necessary, so is educating our own supporters and ensuring that our movement remains clear and uncompromising in its demands.

Our strategy to pass the initiative was to identify existing connections to the members of the council and to reach out to them through these existing social networks. The member initiative forced us to map out our network in an explicit way in an attempt to find connections to all 6 schools of Aalto University. This ‘lobbying’ effort showed that we had much broader support than we had assumed, with students from all across the university in support of our initiative.

Repco discussed the initiative on 21.11.24 and voted on it 12.12.24. We had a representative present at the council meeting on 21.11.24. They participated in the discussion, but unlike at Uniarts or UoH we did not have a presentation for the council to kick off the discussion. The discussion was very formal, with the council members reading prepared statements.

The initiative passed in a narrow vote. The opposition to the initiative was mostly related to the role of the student union and how active it should be in societal issues. A cohort of the members in the Representative Council feel that the student union should have a very narrow focus on advocating for issues directly related to day-to-day university life. This mirrors the politically apathetic Aalto University community.

Our next steps are to work with AYY to pressure Aalto University to join the boycott. Part of this work will be to hold AYY to account, making sure that they go through with advocating on behalf of the boycott. Maintaining pressure through informal means will be critical; otherwise, this issue will be forgotten. It is clear to us that the academic boycott of Israel is not a priority for the university, nor for our student union. Of course, on paper our union now supports PACBI, but the challenge going forward is to transform this policy position into concrete action.

Students from across Helsinki walk out of classes and arrive at the lobby of Aalto University to participate in a sit-in on the international day of solidarity with the Palestinian people. November 2024, Photo: Akku

In the past year, small victories have been reached: the student unions of Helsinki University, Uniarts and Aalto University, as well as SYL, the National Union of University Students in Finland, have officially demanded an academic boycott of Israel. Helsinki University and Uniarts have responded to some of the demands of students advocating for BDS and PACBI boycott calls by freezing exchange agreements with Israeli institutions. The next step for us is to ask, what comes after the passing of membership initiatives? How to get universities to divest, to respond to the full demands of BDS and PACBI calls, including the demand of stopping to financially support Israel? How do we rise to the calls made by our comrades from the Palestinian student movement?

Although this essay focuses on the three capital regions’ institutions, Students for Palestine’s organising has also been active in Turku, Tampere, Jyväskylä, Hämeenlinna, and Kuopio. We aim to strengthen networks between universities in Finland and beyond, recognising that mutual support—both in struggle and in success—is essential to sustaining this movement. Sharing knowledge lightens our collective workload, and relying on each other’s efforts has been crucial to our progress. We hope this text can also serve as a resource for other student movements engaged in similar activism.