Painting about the Zág tree by Carl Gakran

Sanabel Abdelrahman is a postdoctoral fellow at MECAM/Tunis University. Her research focuses on magical realism in Palestinian literature. She completed her doctoral degree at Philipps-Marburg Universität and her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees at the University of Toronto. She is interested in cinema and visual arts. She is a writer of fiction and essays.

Penning this essay has been somewhat of a struggle. Despite my great interest and emotional investment in this eye-opening and painfully pertinent encounter, it was difficult for me to situate my role in telling it. The encounter was between an Indigenous couple (Isabel and Carl Gakran) attempting to resurrect a sacred, endangered tree and a Palestinian (me) bearing witness to the genocide of her people by the same machinery of killing, subjugation, and systematic attempts at dehumanization1. The encounter was on stolen land– Santa Catarina, South of what is currently Brazil2.

The struggle arose from the manner by which I engaged with Isabel and Carl, whose language (Xokleng) I could not speak, nor that of the colonizers of their land: Portuguese. Despite being a little outside the conversation because of the loss of language, palliated by Gabriel, my Brazilian husband, who would relay my words to them and deliver a distorted gist of their deep communication, my and Isabel’s body language was the same. We would point to our hearts, the sky, and the land. When Gabriel translated what she had said, I would nod because I knew.

The struggle arose because I felt responsible for communicating these critical conversations word-for-word, mediating an Indigenous struggle in South America and Palestine; and almost removing myself from the process. Feeling a responsibility to relay every message and impression, I did not linger on this experience at a personal, visceral level. On my second attempt at composing this essay, I wondered: what was this encounter for me?

View from Insituto Zag

When we arrived in Rio de Janeiro for a short sojourn before traveling to the south, I was taken aback by the stunning green that enveloped the fantastic landscapes unfolding before us. I arrived in Brazil aware of and almost tangibly feeling the traces of colonial violence, which was orchestrated so that tall, high-rise buildings could puncture the incredible Latin American green.

We drove from Witmarsum for an hour and a half to reach Instituto Zág. From the car window, I passed buildings and village aesthetics that so strongly recalled none other than Marburg, a town in Germany’s Hessen state where I momentarily lived during my doctoral studies. The German shop signs disclosed the colonial history of the humdrum Brazilian state. It was surprising to see so much Sauerkraut and Würst served outside Germany, a country currently fixating on devising new forms of Palestinian repression. The catastrophic cluster of settler colonialism and German supremacy took on an even more pronounced streak when I learned that Santa Catarina was the first cell of the Nazi party outside of Germany. Neo-Nazi activities persist today3 –having intensified under the presidency of right-wing Zionist Jair Bolsonaro.

I could not help but draw parallels to Israel’s violent sequestering of Gaza from the rest of the world. Prohibiting the entry of food, water, gas, and construction material; cutting off exit routes even for the children it shelled; and preventing the (re)construction of an airport exhibit the same European apparatuses of settler-colonialism that went into the construction of this dam.

The population of the Xokleng people witnessed an outrageous drop because of settler extermination. In 1875, the first Italian colonies were established in Santa Catarina. German settlers had started establishing their violent presence there slightly before.

Xokleng people died from the disease brought by the white invaders when the ‘contact’ happened. This further spread the belief among indigenous people that encountering Europeans made them sick. From influenza, yellow fever, and measles, the first two decades of this ‘contact’ were fatal to the Xokleng. Between 1914 and 1935, two-thirds of the Xokleng people were killed by white settlers’ disease, as well as state-sponsored extermination campaigns4.

From my agitated posture in the backseat, I witnessed through the car window extractivism in real-time. Hundreds of murdered trees stacked up on the road. Headless trunks of wood were bearing witness to an uninterrupted practice of nature killing, which set the scene, literally, for the forthcoming encounter.

As we were approaching the Xokleng territory, I spotted several cottages sprouting from the magnificent shrubs and bluing mountains. The houses were once occupied by settlers who constructed the dam. The Barragem Norte is an ugly, tired-looking dam the state uses to keep the Xokleng people, indigenous to the land, in check. Threatening a flood whenever the Indigenous people dared to resist, this tool of punishment is a solid and robust example of the colonial forms of settler-colonial domination. I could not help but draw parallels to Israel’s violent sequestering of Gaza from the rest of the world. Prohibiting the entry of food, water, gas, and construction material; cutting off exit routes even for the children it shelled; and preventing the (re)construction of an airport exhibit the same European apparatuses of settler-colonialism that went into the construction of this dam.

We had talked about the dam lengthily before the car passed it. I asked to stop and stepped out to commemorate this uneasy encounter with a picture on my film camera. Upon our return to Tunis, I deposited my film in a little photo lab in La Marsa. The man behind the counter informed me in a resigned voice that the film roll was empty. He extended the blank scroll before me, shaking his head as if negating a haunting encounter with the material apparatus I have become so cognizant of.

The Barragem Norte Dam

After many turns and spiraling routes into dusty paths, we reached our destination. We stepped out of the car and were greeted by Isabel and Carl. Isabel is the vice-president of Instituto Zág, and Carl Gakran is the president of Instituto Zág. The institute’s work focuses on protecting the critically endangered Zág/Araucaria tree and preserving the traditional knowledge of the Xokleng people. Carl completed his research on the Indigenous origin story5 or creation myth of the Xokleng people. He managed to record the story in the 1980s, told to him by one of the last elderly members of the community, who is now deceased. His father, Nanblá Gakran, was a celebrated linguist and the first to establish schools for Xokleng children. The Xokleng language and culture were finally freely taught– a means of resistance against the eradication of the group’s presence and identity.

From where we stood, the glorious forests of Brazil extended into the hazy horizon. I felt a lump in my throat as I stood with Indigenous allies at the darkest hour of the Palestinian genocide. The encounter evoked a kind of longing and a stubborn, tenacious hope, which is occasionally painful to maintain.

Fictionalizing nature and materializing the stories around it not only preserved the environment from the fatal obsession with possession that characterizes the colonial mindset but materially manifested an Indigenous-powered way in which this could be potentialized.

After greeting us warmly, we walked until we reached a spot in the mountain where tall Zág trees pierced the sky. Carl pointed to one of the trees and narrated to us the origin story. The Xokleng people emerged from the waters and the earth. When they looked up, the Zág/Araucaria tree was the first thing they saw. He talked to us about the fascinating and expansive Xokleng cosmology where ngayun (‘spirits’) and kupleng ([ghost]-souls) that inhabit trees, mountains, streams, wind, and animals were equal to their human counterparts, living or dead6. The tree thus gained its unparalleled spiritual significance in the Xokleng tradition.

The Xokleng origin story brought to mind a piercing anecdote. It was customary for Palestinians to tie scraps of fabric and rags on tree branches. “In most cases, no one dares to cut the branches of haunted trees, just as it is not permissible to harvest their fruits until the permission of the jinn7 is obtained by placing some food under the trees.”8 This practice took on a graver streak post-Nakba. In Ilyas Khouri’s novel Bab al-Shams (Gate of the Sun)9, haunted trees in Palestine were not feared but revered as liminal resting places where the souls of martyrs would take refuge.

The jinn in Palestinian lore, similar to the ngayun and kupleng in Xokleng tradition, are treated like their human counterparts and placed in the vital overlap between Indigenous peoples and their land. The closeness (often a material binding) to land, manifested in spectral agencies, poetically exemplifies Indigenous storytelling around climate fiction. Fictionalizing nature and materializing the stories around it not only preserved the environment from the fatal obsession with possession that characterizes the colonial mindset but materially manifested an Indigenous-powered way in which this could be potentialized. Rather than offer adventures into speculative possibilities, this materialization of climate fiction provides tools for imagining and reifying forms of liberation, unity, and retrieval of material and immaterial things the colonizer has robbed.

The presence of the Zág tree has been drastically dwindling owing to deforestation practices, initially orchestrated by the colonizers and later by greedy companies- an injurious practice that protracts today. The tree is supposed to live for thousands of years. It is an agent and a signifier in Xokleng mysticism and world-building. Today, a striking percentage denotes the number of trees that survived the extermination: less than 2%. This staggering number prompted Isabel and Carl to start their initiative under Instituto Zág.

The Xokleng do not see that the Zág tree is separate from their existence as human beings. The uprooting of a tree is as painful and mournful as the death of a loved one (or, more accurately, under settler-colonialism, their killing). Isabel shares with us that the person who plants the seed of the Zág tree must make a wish that will eventually be granted to them. The person’s thoughts and feelings passing in the moment of this act will forever remain within the tree, which will grow around 40 meters into the sky and stand in its land for thousands of years.

I had the honor of being invited to plant a Zág seed with my hosts. Isabel carefully handed me the seed. The seed was wooden and fist-sized. I had noticed the discarded seeds (following successful germinations) left as snacks for animals wandering by. The experience was doubly emotional as Isabel, Carl, and their child honored us by performing an Indigenous ceremony to commemorate the moment. Singing while wearing a magnificent feather crown and the Palestinian kouffieyye, Isabel’s union with the tree, which she generously invited me to, was a heartfelt and tactual solidarity with the Palestinian struggle.

Barehanded, I removed the soil with the help of the singing child. I gently planted the seed that was quivering in my hand– anxious to return to its ancestors and bring back the life that was robbed of the people and the trees alike.

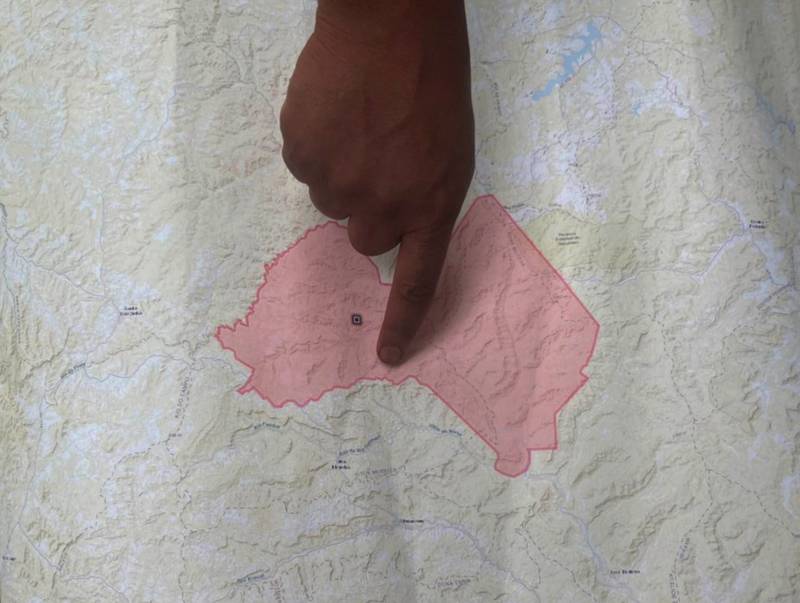

Carl Points to Xokleng Territories on a map

The population of the Xokleng people witnessed an outrageous drop because of settler extermination. In 1875, the first Italian colonies were established in Santa Catarina, and in 1914, German settlers began establishing their violent presence there. When the ‘contact’ between the Xokleng people and the German invaders happened, many died from European diseases. This further fostered the belief among the Xokleng that encountering Europeans made them sick. Learning these figures as the death count of Palestinians in Gaza was increasing exponentially shrouded the encounter with a kind of melancholy that the colonized know so well.

Zag Saplings in a Nursery

The four of us walked, Isabel, carrying her child and the family dog tagging along, to observe the nurseries of the sacred tree. The infant saplings huddled up inside wood squares. The discarded seeds were a testament to the tenacity of Indigenous nature and its many labors to come. As we trod the forests whose trees held the souls of the revered dead, Isabel told us that despite the settlers’ fanatic attempts at extermination, the population of the Xokleng people has been increasing. Going from 104 members following settler extermination, the Xokleng people are now 2,500 members strong.

Carl and Isabel recounted how a delegation once arrived under the guise of forestry development only to plant Eucalyptus trees, which are invasive to the territories. This seemingly innocuous practice brought to mind Israel’s settler-colonial practice of planting European trees in Palestine in an attempt to make the land, which is foreign to its people, look closer to the Europe many hailed from.

Sitting in the diverging space between two great tree trunks, his right palm resting on the tree as if on the shoulder of a human companion, Carl talked to us about the Xokleng dream of (re)unification. The Xokleng community awaits a verdict from the Brazilian Supreme Court, which, if granted, will help them retrieve double their Indigenous territory. If successful, they expect a prolongation of state violence and settler aggression, especially from those who will be forced to cease their ongoing colonization and leave the territories. A lot of anticipation and anxiety fill this time of waiting. There is also a great deal of hope. Isabel and Carl similarly expect the retrieval of their rightful autonomy over their stolen lands. Reunifying with kin while retrieving their language, religions, and customs will become a closer possibility.

Isabel and Carl explained that two other ‘contacts’ threaten their community: the Evangelical church and the companies working on the de/re/forestation on their land. By effacing the rich and historic tradition of Indigenous religions, especially concerning the group’s non-human actors, the Evangelical church is eradicating entire systems of collective world-building, cultural preservation, and Indigenous unity.

Claims of green justice have had a precipitous effect on the Zág tree and the Xokleng community. Carl and Isabel recounted how a delegation once arrived under the guise of forestry development only to plant Eucalyptus trees, which are invasive to the territories. This seemingly innocuous practice brought to mind Israel’s settler-colonial practice of planting European trees in Palestine in an attempt to make the land, which is foreign to its people, look closer to the Europe many hailed from. Often, those invasive trees caught fire spontaneously– further denuding the settler’s ignorance of the land to which they claim to be Indigenous10.

In my second attempt at writing this essay, I understood that the mere documentation of the encounter was erasing my role as a Palestinian, specifically in creating vital connections between the Palestinian and Indigenous struggles. Perhaps I had been wary of overstepping as an interlocutor or of misreading the terrain (even at a literal level). Yet, talking with Carl and Isabel while gazing at the little saplings that animated overlapping images of liberation as the genocide unfolded was more than a reprieve.

I imagined the camera roll- which betrayed me by erasing my Palestinian presence on Indigenous land- filled with images of Palestinians and their Indigenous kin. The collectively imagined and conjured images fill the void of settler colonialism; the empty camera roll a potent space for transgressive solidarities and potent exchanges. The image of my encounter will forever be printed onto the blank roll- whether or not acknowledged by the camera’s colonial gaze.

Appendix

Summary in 23 points of one of the main stories of the Laklãnõ/Xokleng people, transcribed in the 1980s by researcher Nanblá Gakran, as told by one of the oldest elders of the time, Kãnnhãhá Nãnbla, who has since passed away. [Translated by Gabriel Possamai]

The Generation of Man

Kânhâhã Nãnblá (Santos 1997:151)

- There are two ways in which man was created.

- The Klēdo came out of the Mountain.

- And the Vãjēky came out of the water (probably from seawater).

- They wanted to come out and waited below the water.

- Meanwhile, Plandjung came rising, making a path.

- When he finished making the path, he returned to fetch the others.

- Then they came up with him.

- Wherever they stepped on land, they prepared a place and celebrated by dancing.

- Meanwhile, Plandjung continued making a path.

- Then they followed him and stopped again to celebrate.

- At that moment, they heard other men coming behind, and Vãjēky became afraid.

- So Vãjēky created a jaguar.

- And Zágpope Paté painted the jaguar for him.

- On its neck, he left marks painted in a closed, rounded shape, and others long.

- Zezé painted it with long marks and circular ones on the jaguar’s shoulder.

- Txu Txuvanh painted closed, rounded circular marks on its back.

- And they finished painting the jaguar that Vãjēky had created.

- And he said: “My creation now roars however it wants.”

- Then it roared and went after the others to eat them.

- Now, the painting (markings) of Zágpope Paté is closed, rounded, and some long.

- And the painting of Zezé is now long with some circular ones.

- And the painting of Txu Txuvanh is now circular, and others are closed and rounded.

- Now, their generation wears the painting (markings) of their ancestors.