Digital Commoning Practices was on view in Oksasenkatu 11 on March 6–28, 2021

Ksenia Kaverina (b.1988, Saint Petersburg) is a curator and researcher with a special passion in languages, translation and transdisciplinary collaborations. Her doctoral dissertation in the making considers globalisation-conditioned changes in knowledge production and perception, in exhibitions, biennales, museums, universities and other potential sites of curatorial interventions.

Digital Commoning Practices is an exhibition that is best thought of as a station. A station has no beginning or end within a particular path. It is part of a network of other stations – like in a railroad, they are interconnected. A physical installation, Digital Commoning Practices, is an iteration of the Station of Commons initiative1 by Grégoire Rousseau and Juan Gomez, opened for the public on March 6th, 2021, in the artist-run space Oksasenkatu 11. Over the next three weeks, it hosted concerts, workshops and talks by a network of practitioners and researchers interested in experimenting with technology, commoning, and learning. According to the website, the exhibition produced a “timeline to articulate different temporalities”2. Writing about it, I wanted to emphasize the importance of encounters, extend the text with references, and convey a sense of fleeting time.

The following reflection resulted from a conversation with Grégoire Rousseau and Constantinos Miltiadis in Oksasenkatu 11, on March 24th.

Week 1 – contemporary form

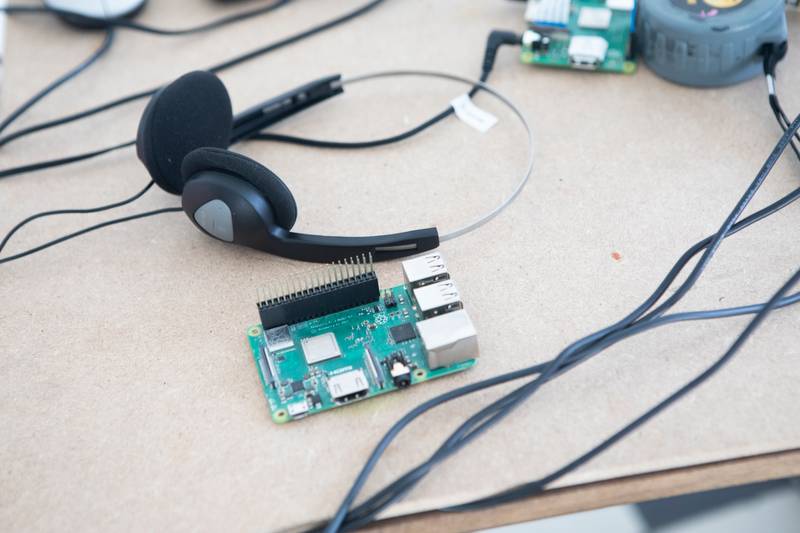

It is March 13th, 2021. A stricter lockdown has just been introduced in Helsinki, everything is closed, but you can still visit private museums and galleries by appointment. With my friend Dahlia, we just saw a comprehensive Finnish ryijy3 exhibition in Taidehalli, and walked down the slushy streets of Töölö. As we walk past Oksasenkatu 11 gallery, through the window, I notice Grégoire Rousseau sitting at a table, surrounded by wires and screens, a microphone stand in front of him. A video projection of what appears to be two female avatar faces4 can be seen through the window; the gallery space looks quite empty otherwise. Grégoire seems busy, so we wave hello and continue our journey. The intriguing concert program of Digital Commoning Practices is already online, but as it happens too often these post-winter days, the Zoom fatigue is especially acute in the evenings, so I put it off for later.

Last July, the Station of Commons provided an alternative technical infrastructure for a symposium, What System Actually?5, in the Kassel Kunsthochschule, where I also took part. Participants could choose to join the symposium using Zoom or the Station, where it was also possible to exchange files and write on a shared notepad freely. Also, since its inception, same as during this exhibition, the Station hosted online music events in the form of open-source live streams featuring sound artists and curated by the *\N10 collective*. So, regarding pandemic circumstances, the choice of hosting a three-week program online in the case of Digital Commoning Practices was not explained by a constraint, but rather by an intention of working collaboratively and internationally. The program spanned over the virtual rooms of the program guests – from London, to Athens, to Vallila (Helsinki). The Station live stream was sometimes hosted by Constant6, a non-profit, artist-run organization based in Brussels. Knowing his versatile practice as a musician, educator and engineer, I wondered what Grégoire’s goal with organizing a physical show was.

Week 2 – commoning

The following week, an email from Vidha and Elham pops up in my mailbox – they are inviting me to write an exhibition review for NO NIIN. I feel lucky about this invitation, and it will motivate me to follow the online program – next on is Commoning Education/Educating the Commons part, and on a Friday evening, March 19th, I tune in for a conversation between Grégoire, Nora and Constantinos. They are discussing questions of the use of technology, power, knowledge and commoning. Participants can listen in via the Big Blue Button server and ask questions, but don’t offer a video option. The next day, I visit the gallery and enjoy the long moment of chatting with all three of them; we go through the books that Constantinos brought for the project and agree on a formal interview in the gallery next week.

Station of Commons is a research project on digital commoning practices

Vagrant library set up by Constantinos Miltiadis / Ground floor in the gallery space

We discussed at length what commoning is. The word is not frequently but more and more used as a verb, as commons in the making; it seems safe to say that there are many understandings, but not one definition. According to Constantinos, an architect by training, who in turn refers to Stavros Stavrides, “there can be no model of commoning – commoning can be observed when people come together to produce space, to produce themselves, all the while thinking through a ‘we, which results in unique singular instances of ‘commoning practices’. Commoning can take the form of resistance through spatiality or the feminist hacking of space. In the case of Digital Commoning Practices, it extends its reach through an exhibition, networks, the internet, and friendships. Part of the installation was a physical library – Constantinos underlined the idea that the library doesn’t have to contain multiple items or large volumes of books. Instead, connecting through stories, sharing and making openly accessible is also a way of producing space, especially when we cannot do it physically.

Community is essential in the process of commoning but is not the same, or at least, it is not the goal or origin of the common. The common is also distinguished from the private or public. This is perhaps more difficult to grasp; there is a certain idea of radical openness in the common – anyone can join, as commoning always welcomes new know-how and knowledge, embedded within a dynamic always in the making. It is productive to imagine commoning as a digital network, where, unlike with embodied presence, it’s impossible to be simultaneously present and absent – you are either online or not.

Week 3 – technofeminist narratives

On the due day, I come prepared with questions and a recorder. Grégoire and Constantinos meet me with their own recording device as well, our conversation will also be a way for them to archive the show. We spend about 2,5 hours talking about technofeminism, commoning, and the origins of the Station of Commons. I’m trying to use the right language and test the boundaries of this project—which feels to be ever-expanding and involving more people than it appeared to at first. In the end, Grégoire asks whether I will join the VPN workshop on Saturday. After that, the Station of Commons in Oksasenkatu is dismantled – disappearing only to reappear somewhere next.

A Cyborg Manifesto, written by Donna Haraway in 1985, made clear that modern technology not only enables but also generates new social relations7. Expanding the cyberfeminist theoretical understandings of technology-conditioned changes in society, technofeminist (artistic and activist) practices8 chose the invisibility of digital infrastructures, as well as technology’s biases, as the medium for their interventions. Artist Cornelia Sollfrank has been active in the field since the 1990s, with numerous projects that used hacking and creative coding to challenge the hierarchical and patriarchal structures in tech – reinstating the power of decentralization and commoning. The discourse of technofeminism is instrumental in understanding the issue with technology: “It [technology] is designed to seduce and to persuade. It is part of the deal, the companies give you something that looks nice and often is fun to use, but then you pay the price – which we often do not even know exactly. And honestly, who has the time and the interest in exploring all the tricks needed to protect oneself? Everything works best if you don’t use any additional precautions”9, said Sollfrank in a recent interview.

Why not happily continue using technologies that are supposedly a free solution, made readily available for all? “Digital literacy” implies literacy when we interact with anything digital as end-users. Architect and researcher Dubravka Sekulić problematized colonialism, universalism and Zoom in the introduction to her talk – as technologies, that come with a certain violence. We give not only our data and privacy in exchange for our Zoom time. Sekulić shared recent examples where Zoom canceled scheduled talks for ostensibly political censorship reasons.

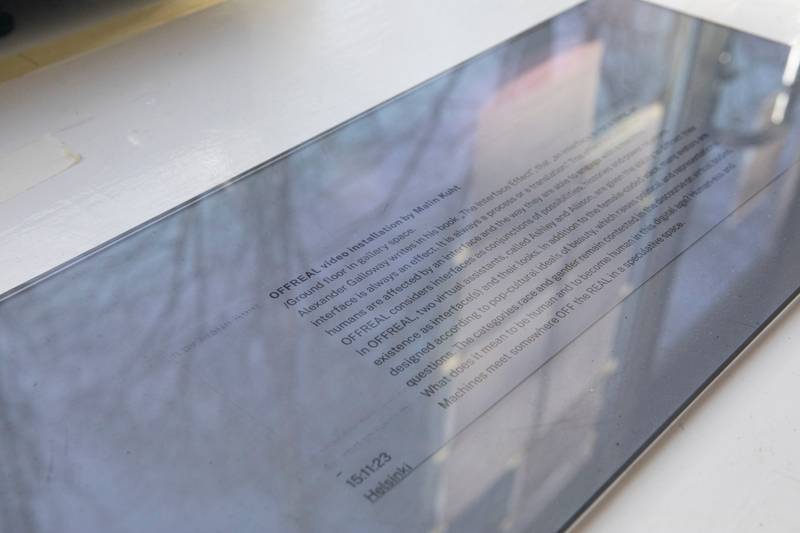

OFFREAL video installation by Malin Kuht / Ground floor in the gallery space

Access to audio is always present on the Station of Commons website

Learning through collaboration is at the core of open source software, based on four principles of the General Public License: (1) anyone can download it, (2) can make it their own, (3) can improve it, (4) and redistribute it. This work is invisible, but we are all familiar with it, like, for instance, Wikipedia, which is built on voluntary contributions and labor.

Terms and conditions are the focus of close attention for technofeminists. How to infrastructure otherwise, with Femke Snelting, Jara Rocha, and Martino Morandi detailed their issues with servers, and discussed how one could use servers on our terms. Increasingly, servers are commercial, and you need expensive servers to host a discursive program of an exhibition, especially when it comes to video (as in Zoom or Teams). Audio, Grégoire’s preferred format, is easier to stream; it requires a minimum of resources to bring people together – you do not need digital technology or very high-speed internet. Access to audio is also easier for users, and is always present on the Station of Commons website.

At the same time, many technologies that we use today reached us through an open source process, made without wanting anything directly in return. Software developer communities have been largely built on mutual support and teaching. Learning through collaboration is at the core of open source software, based on four principles of the General Public License: (1) anyone can download it, (2) can make it their own, (3) can improve it, (4) and redistribute it. This work is invisible, but we are all familiar with it, like, for instance, Wikipedia, which is built on voluntary contributions and labor.

In the conversation with curator and educator Nora Sternfeld, the question of “re-commonalisation” emerged in relation to education – Sternfeld has written extensively on museum education, and her latest book is The Radical Democratic Museum10. Following Paolo Freire, Sternfeld reminds that education has never been neutral, and has direct relation to the power relations in societies, including when it is being critical of this power. Many institutions quickly switched to an online mode of exhibition-making, especially during the pandemic; it was generally celebrated that people could explore exhibitions, guided tours, and museum collections from their homes. Sternfeld reminds us that the current digitization programs of museums, with the claimed goal of making knowledge more accessible, are often realized through partnerships with private companies11. She emphasizes the need for open source museums. At the same time, Aideen Doran writes, many wonderful free and open online catalogues of the world’s knowledge today, such as Europeana, the Digital Public Library of America and Project Gutenberg, are facing significant limits being contingent on funding or the restrictions of copyright law12. Built with the similar goal of facilitating access to knowledge and skills, many online platforms like Coursera, Udemy, or LinkedIn Learning, openly position themselves as educational marketplaces, while learning experience and content is mediated by commercial software also at universities and schools – making one pose the question, can we imagine sharing and creating knowledge differently?

Digital libraries at least can be sites of resistance: the online library project Public Library/Memory of the World13 was established to offer simpler access to knowledge and preserve documentary heritage through collaborative means. Its creator, ‘cyber-librarian’, artist and free software activist Marcell Mars, also participated in the exhibition program. In the Public Library, users can actively contribute to and control the catalogue in conversation with each other (similar to Wikipedia). Recommendations for readings come from the users and not from algorithms.

Lately, I have been thinking of the (imaginary) Feminist Server, she who “[t]ries hard not to apologize when she is sometimes not available”14. Like her, I also want to avoid stoic efficiency and immediacy, but I also want to change my mind and embrace the urgency of a moment – here, I guess, comes the difference between server design and human beings.

For the ending weekend of the exhibition, Grégoire planned to organize a workshop on VPN. The duration of the workshop was open – the audience might be people who are already savvy about the technical terms and ways of programming or they might be observers and enthusiasts. Grégoire said that he planned to start by doing, then find an interest, create a space around it, and finally figure out how people can be in the space together. The internet allows us to connect and exchange information, but our relation to the other is always one-way: connection goes via a protocol (IP), managed by a central sever, that is in turn managed, monitored and controlled by an Internet Service Provider. With a VPN, we can situate ourselves still within the private infrastructure of global communication, and at the same time on its own margin of operation. An Open Source Virtual Private Network provides a para-structure of sharing within, against and beyond capitalist logic of concentration of control and power, sometimes referred as the digital panopticon. That very practice of emancipation operates at the core of Station of Commons: the development and re-appropriation of the digital means of communication, distribution and production.

One critical learning that I take from the Digital Commoning Practices is that we need to pay increased attention to what (and who) facilitates our physical and digital presence while we can; or, as Constantinos put it, we should ask what kind of freedoms do we have to engage with infrastructures ourselves. Lately, I have been thinking of the (imaginary) Feminist Server, she who “[t]ries hard not to apologize when she is sometimes not available”15. Like her, I also want to avoid stoic efficiency and immediacy, but I also want to change my mind and embrace the urgency of a moment – here, I guess, comes the difference between server design and human beings.

Thank you to Grégoire and Constantinos for being generous with their time and sharing, to NO NIIN for this invitation, and to Dahlia El Broul for careful editing.

Full list of artists and contributors of the exhibition, as well as the recorded talks Intersecting Commons by Stavros Stavrides with Selena Savić, Station of Commons and Nora Sternfeld, Unsettling the Universal: Really Useful Commoning by Dubravka Sekulić, and On Variations Of Gender And Technology Trouble by Cornelia Sollfrank are available in the exhibition archive: https://stationofcommons.org/events/digital-commoning-practices-archives.