Studies depicting Waleed Mohammed’s signature reimagining of archival studio portraits from Sudan

Rahiem Shadad is Sudanese cultural researcher and curator now based in Nairobi. He was previously the director of The Rest, a residency for displaced artists in Nairobi. Rahiem is passionate about shedding light on the conflict in Sudan and its underreported social consequences.

Since 1989, Omar al-Bashir has ruled over Sudan in what was known to be the most tyrannical and segregative governance in Sudan’s modern history. Under his rule, arts and culture faced many limitations, such as confiscating artistic productions, closing galleries, closing publishing houses, closing public cinemas, and limiting access to public spaces. The introduction of the Public Order Laws, a set of rules on social behaviour, dress codes, and public conduct, often enforced through an autonomous judgement of security forces or police, further scrutinised several forms of artistic expression.

Under these oppressive cultural politics of over 30 years, art that expressed liberal and inclusive ideologies was confined within the closed walls of art studios and foreign institutes. The mere practice of art itself was an act of rebellion. However, in 2018/19, the Sudanese people had had enough of the regime and revolted in what is known as the “Bread Revolution”1. Artists were at the forefront of this revolution, painting hundreds of murals across the capital, Khartoum. They designed protest posters and wrote chants for demonstrators to sing as they marched. A stage was even built at the heart of the sit-in protests, on the street in front of the military headquarters in the capital, and concerts were held for weeks. The protests ignited an explosion in the field of arts, leading to the opening of dozens of galleries within months of Omar al-Bashir’s downfall.

I, too, started my curatorial journey in 2019, initially by following and publishing artistic productions during the revolution and later by co-founding my commercial gallery, Khartoum’s Downtown Gallery, in December 2019. I had the privilege of working with over 65 artists in my gallery, allowing me to witness how the art scene transformed and claimed the slogan of the revolution—‘to Rebuild Sudan Together.’ It was an inspirational period. Downtown Gallery hosted all three artists, whose interviews are included in this text, in various exhibitions throughout its four years of operation.

A mural in Khartoum painted by artist Issam Hafiez in 2019. It translates to “A Revolution of Awareness / Knowledge”

Young gallery interns help to hang the art. Downtown Gallery in Khartoum, 2022. Photo: Rahiem Shadad

This time also marked the beginning of Sudan’s transitional period, during which a power-sharing agreement was reached between the civilian coalition and the military. At the time, this arrangement was represented by two military entities acting as one: the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Many protesters and civil organisations opposed legitimising two separate military bodies within the transitional constitution, cautioning a fragile and volatile situation that later served as an entry point for global and regional actors to exert influence. This division allowed foreign powers to channel funds, weapons, and political support to competing sides, effectively turning Sudan into a battleground for an externally fueled conflict and escalating the war.

On October 25, 2021, a coup took place. The RSF and SAF turned against the civilian government appointed by the revolution, crushing the hopes of countless young Sudanese who had dreamed of freedom, peace, and justice. Less than two years later, on April 15, 2023, war erupted between the SAF and RSF in Khartoum. Both military bodies represent specific regional and international interests and, thus, are backed and funded by Egypt and Iran on the SAF side and the UAE and Chad on the RSF side. Heavy artillery and airstrikes ravaged the city in what is mostly a proxy war. Nearly half of the city’s 12 million residents were forced to flee in what has since become one of the largest displacement crises in modern history. Within weeks and months of the conflict, more than 11.5 million people had been displaced. The RSF, backed by the UAE, expanded the war zone beyond the capital, committing human rights violations in over 13 states, such as Khartoum, Aljazirah, West Darfur, Central Darfur, and North Darfur states. On the other hand, the SAF responded with heavy airstrikes that made many civilian spaces inhabitable.

The vast majority of civilians were forced to abandon their belongings. As the conflict consumed Khartoum and expanded throughout 14 of Sudan’s 18 states, unquantifiable volumes of memory were lost or destroyed. Personal and public archives, including artworks, artefacts, and publications, were engulfed by the deepening crisis; museums, galleries, and art studios were shelled and burnt to the ground.

Amidst this destruction, the need for a stable environment where cultural expression could continue became urgent. Of the many places the Sudanese people sought refuge in the region, Kenya has been particularly appealing to artists, filmmakers, cultural practitioners, researchers, and political activists. This is due to many factors, some date back to the formation of art and design universities in East Africa in the 30s and 40s and the exchange of knowledge and teachers between Makerere University in Uganda and Nairobi University; and Khartoum University and Sudan’s Technical Institute (now known as Sudan University of Science and Technology). Sudan’s bond with Kenya that transcended proximity flourished further in the late 90s after the Omer Albashir regime forced artists into exile, and many moved into Nairobi, such as Eltayib Dawelbeit, Abushariaa Ahmed, Yassir Ali, and many others. The first batch of artists greatly benefited from the shifts in Kenya’s cultural policies that resulted from the constitutional amendment that allowed for multiparty democracy. The expansion of political freedom had a direct effect on the independent cultural movement in the country, and many galleries and theatres were formed in the early 2000s. This, along with the formation of many artists’ collectives such as Brushtu, Kuona, and GoDown, laid the base for many East African artists to build curiosity towards Kenya. For Sudanese artists in particular, there was a hunger for understanding the African identity that was suppressed by the islamo-arab governance and cultural agenda that was imposed since the late 1970s. Sudanese artists wanted to be familiarized more with the African aspects of the Sudanese identity – a part of who they are that they rarely were able to express under the racist and segregative policies of Sudan at the time.

The influx of such creatives into Nairobi revitalised many institutes and programs, which began adjusting their priorities to accommodate the incoming refugees. For instance, The Rest, an artist residency founded in October 2023, supported over 40 displaced Sudanese creatives new to Nairobi, funded by USAID, Ford Foundation, and the Goethe Institute.

My move to Kenya started with a phone call inviting me to curate an exhibition with Alliance Francaise that advocated the situation in Sudan. In July of 2023, I had just finished an art performance in an exhibition in Cologne and had seven days remaining on my Schengen Visa. With the destruction of Sudan’s international airport, I had no place to fly to. A fellow Sudanese curator and a dear friend of mine, Azza Satti, who has lived for 25 years in Nairobi, told me to come to Kenya and join forces to educate people about the war and create a port for Sudanese artists to land on. I arrived in Nairobi in July 2023 and immediately started lobbying cultural organisations such as the GoDown Art Center, the Alliance Française, and the Goethe Institute to engage with the coming flux of displaced Sudanese people. Since most Sudanese obtain tourist visas upon arrival in Kenya, they are not legally categorised as refugees despite their statelessness. Tourist visas also do not allow them to work or own bank accounts. Access to Kenyan work permits can cost up to 8,000 USD for the first year – an impossible sum for the vast majority of civilians fleeing a war and forced to abandon most material possessions. In October 2023, along with fellow curators, I founded The Rest, a residency program that evacuated artists from the conflict zones in Sudan into Kenya, helped them settle in the new environment of Nairobi and hosted them as they returned to creating again. Unfortunately, due to a funding shutdown, the residency closed on December 15, 2024.

Closing remarks for a chapter of The Rest Residency behind Nairobi’s Circle Art Gallery in August 2024

The challenges newly arrived artists and civilians faced were immense, marked by the trauma of war and the practical difficulties of navigating a new, often precarious, existence. The individual journeys of the following artists began within this context of ongoing displacement and the relentless pursuit of safety.

In June 2024, young and upcoming artist Waleed Mohammed left the conflict-hit zone of El-Haj Yousif in northeastern Khartoum to Port Sudan and then to Nairobi.

Waleed is a graduate of the Faculty of Fine & Applied Arts at Sudan University of Science & Technology – one of the oldest schools in the region and the alma mater to prominent African artists such as Ibrahim Elsalahi and Kamala Ishaq. Already gaining attention in Sudan’s nascent art scene, he organised his first solo show at age 21 and painted multiple murals around Khartoum. In June 2024, over a year into the SAF and RSF conflict, Waleed left his family home in Bahri. By then, the war had swallowed most of Khartoum, leaving him uncertain of returning. The city that had once nurtured his artistic journey—its bustling markets, fading murals in muted jewel tones, and turpentine scent in his studio—had become unrecognizable. Like many Sudanese artists, Waleed arrived in Nairobi with nothing but fragments of memory and an urgent need to create.

“When the war started, I was living in El-Haj Yousif (Khartoum Northeast), and my studio was in downtown Khartoum,” he explains from his Nairobi home studio that he shares with his flatmate and fellow Sudanese painter, Hoizaifa El-Siddig. “I couldn’t reach my studio again, and I lost all my artwork and passport in the studio. I moved with my family to Wad Medani in Aljazira state, and I focused more on photography.”

But it didn’t take long for the war to spill into Wad Medani, too. Waleed and many others were forced back to El-Haj Yousif, living on the periphery of the conflict. “Without my passport, leaving Sudan was difficult. I had to wait for a new one while awaiting confirmation on a grant I applied for from the Martin Ruth Initiative (MRI) for at-risk artists.” After fourteen months of living in or adjacent to active conflict, he reached Nairobi through the MRI grant for artists, facilitated by the Goethe Institute (Nairobi).

Known for recreating archival photographs from Sudanese studios of the 60s-80s into oil and acrylic paintings, he highlighted the unique culture and worldviews of Sudanese people during those periods. By revisiting such photographs, he explored the dynamics influencing his own evolving identity. In exile, his art transformed. His practice, which once explored the past rifling through reimagined studio portraits and archival photographs, became a meditation on displacement, on the eerie familiarity of foreign places, and on what it means to belong when home no longer exists.

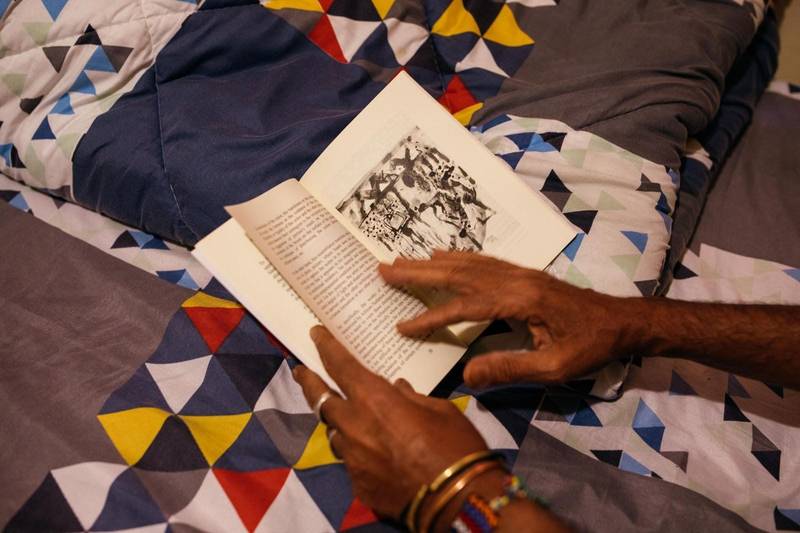

In Nairobi, his bedroom doubles as his studio. He keeps a stack of photographs from Sudan and picture books by his bed, which he often flips through for inspiration and nostalgia. Some of the photos are copies he reprinted in Nairobi. These items bind him back to Sudan—a portal into his former self and different personal interests.

Waleed Mohammed painting from his bed

Waleed Mohammed in his bedroom in Nairobi, which doubles up as his painting studio, looking at archival material–some of the few possessions he managed to bring from Sudan.

Waleed Mohammed has been in Nairobi for over seven months now. He says the early months were refreshing and enjoyable, and the grant funding supported him well. He was even able to rescue his family from Khartoum and move to Egypt—a difficult decision after the family business, a hardware store, was looted, a common occurrence in war-torn Sudan.

He could not accumulate savings from the grant since he prioritised evacuating his family. Just as his family entered Egypt, the grant ended. This shocked him with a different reality. His perception of navigating Nairobi as a space for displaced individuals also changed. “There’s more exposure in Nairobi, a wider market, but there are practical challenges. In Sudan, whether things were good or bad, you always had a home to return to. The stress of paying rent in one’s home country would never be as critical as you experience in exile.”

“How people experience art in Nairobi is very different from Khartoum; therefore, its creation is also different.” There is an emphasis on distinction rather than personal expression. His works now are physically larger and more experimental – a direct translation of what he has perceived from his Kenyan peers. The works increasingly express political views, reflecting his reaction towards the conflict. His latest project links old photographs to the idea of displacement and migration. His subjects are now painted in environments emanating foreignness and oddness. The paintings express the relationship between the displaced person and the hosting space and the mutual influence they have on each other.

It is impossible for him not to long for his previous life. “I miss the sounds of the children in our home as they play. I miss the neighbourhood and the people I would see regularly. I miss all of Sudan, honestly. I call my friends and relatives regularly to soften the separation, although each one is in a different place. Talking to them gives me a small amount of confidence that things are the same. I don’t think I will return anytime soon, even if the war ends today. But I still might go just to check on my studio.”

In the area of Kilimani where he now lives, there is a Sudanese restaurant called Jaytaa, which translates to “it’s a mess” in Sudanese slang, a pun reflecting the times. It opened after the conflict, along with a coffee shop, becoming a meeting place for Sudanese youth in exile.

Jaytaa Cafe, a meeting place for Sudanese youth in exile

Yathrib Hassan lived with her family in the old city of Omdurman before the war. Her home in Omdurman resembled many of the old neighbourhood cultures in Sudan—the walls between neighbours are built short, encouraging a sense of collectivism and community. Neighbours would call her from over the wall to share food or chat. At the outset of the war, a stray bullet killed her aunt. The family rapidly fled to a relative’s home in the southern section of the city. Three weeks later, her family moved to Aljazira Aba in the south of the White Nile. From here, Hassan continued southerly toward Juba, South Sudan’s capital, and then to Nairobi.

Born in El-Obeid in 1999, she graduated one year before Waleed Mohammed and arrived in Nairobi under the same program as him. Her sister Heraaa, a sculptor, accompanied her. Together, they share a studio in Nairobi’s Kileleshwa neighbourhood. “Life in Kenya is bittersweet. The country, from its proximity to Sudan in terms of scenery and people’s culture of openness, makes it easy to fall in love with it. The country is beautiful, but without a stable income and the paperwork, the uncertainty places massive anxiety on the exiled Sudanese individuals. ”

She agrees that artists in Kenya feel a greater responsibility to provide weightier perspectives, whether from their culture or personal life experience. In this setting, her artistic style has become more dynamic; she feels more comfortable placing lines over her hues and colours, as opposed to her previous paintings, which she describes as more classic in composition. Furthermore, the subject matter of her work has shifted towards a politically charged exploration of Sudan’s current state and the war’s devastating impact.

Yathrib Hassan in her home studio, in front of her latest painting in progress, which she says was inspired by memories of dancing in the rain with her sister outside their family home in Khartoum.

“The situation in Sudan today could very easily bring forth a separation of the country into the North, East and West. It’s important to me that the art I create today inspires unity and cohesion. I feel that my way of creating art now is more inclusive and has the way to truly zoom into specifics.” WHAT ABOUT US is a sentiment reiterated throughout most of her present work. As an Almiseerya – specifically Almiseerya Zorog – she comes from an Arab nomad bloodline destabilised by Western Sudan’s politics for over two decades.

Passionately responding to this dimension of her identity, she maintains, “It is more important to me to talk about the culture of my tribe and the many beautiful old stories my grandmother told me and my sister than to talk about the horror and the political history.” The conflict today has made many of the archives related to identity to be lost, creating a further disparity in how youth would self-identify and relate to the space itself. However, with the fallibility of memory, that cultural background only makes brief appearances in her work.

“My family used to have many photo albums at home, which now I know might have been lost forever. When I left, I couldn’t take any of my artworks.” A talisman that Hassan uses to ground her as she navigates displacement is a small bag of “Wadie”,—a small seashell with many cultural connotations. Wadie is commonly used for fortune telling in coffee ceremonies. ٍShe also has a doum fruit, which looks like a rock to someone unfamiliar with the fruit she picked from a tree during her time in Al Jazirah Aba.

With her family scattered across Aljazirah Aba and the United Arab Emirates, she does not believe this war can be won–besides the bloodthirsty warlords, no one wants this. She does not consider the current advancement of the SAF a victory since it will have dire consequences for civilians.

“Wadie”, that Hassan brought from Khartoum, is used to tell fortunes during coffee ceremonies.

A different experience is shared by the prominent Sudanese painter and filmmaker Issam Hafiez, a multimedia artist born in 1959, whose work is inspired by the people of Sudan. He graduated from the Faculty of Fine & Applied Arts in 1982. In the year following his graduation, Hafiez lost a dear friend to the tyrannical regime of Gaafer Nimeri (1969–1985). He was affected by the idea that the state can delete someone’s existence just because they advocated for equality and justice. Imprisonment, torture, and the death of political activists were common characteristics of Nimeri’s regime.

His work has been in the United States of America, the former Soviet Union, Egypt, Britain, Syria, the United Arab Emirates, Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia and Germany. Since the early 2000s, he has frequented Nairobi, participating in exhibitions such as the Art Auction East Africa organised by the Circle Art Gallery. His roles expand beyond the fine arts. As the founder of the Child of Darfur Initiative in 2007, which uses photography to shed light on the suffering of children in Darfur under the Omer al-Bashir governance, the organisation has garnered massive amounts of aid and clothing for Darfur’s internally displaced persons. He also spearheaded efforts to archive cultural productions in a project titled Sudan Memory, funded by the British Council in Sudan for digitising and opening access to Sudan’s cultural archive. Although he’s familiar with Nairobi culturally and geographically, he never imagined relocating there, especially at his age.

Issam Hafiez at his home in the Nairobi West neighbourhood of the Kenyan capital city

Booklet of Issam Hafiez’s recent exhibition, 10th of January, Once Again at Kemet Arts.

Printed copies of old newspapers (1955) announcing the independence in Sudan, a film screening schedule from the 80s, and advertisements from Sudan Airlines about trips to Beirut in Issam Hafiez’s bedroom

Issam Hafiez in his sitting room in Nairobi, crowded with his work and printed pictures of his friends.

His long-standing relationship with Kenya made the country the obvious choice when war broke out. Along with a fellow artist from Khartoum, they travelled by road to Addis Ababa, then flew to Nairobi in July 2023.

One day in early February, Hafiez was at his apartment in the Nairobi West neighbourhood, watching an Al Jazeera documentary on the trains of Sudan, once the largest railway network on the continent, back when they were running in Western Sudan. “When I was in my final year of university, in 1981, we used the train to go on a field trip to paint the landscapes of Darfur. I was recalling those memories, and then this documentary came on. You can’t make this up!”

Hafiez’s apartment is crowded with artefacts from his past, of a different Sudan – photographs he’s taken, old advertisements, notes from friends, and his paintings. His living room has an iconic poster of Ibrahim El-Salahi, whom he considers a mentor and a great friend. “I’m bringing my home from Khartoum 3 to Nairobi through my paintings, through the way I’m designing my apartment, the “bakhour” (scented wood), the music I play while painting, and the posters I’ve printed and placed on the walls. This experience is the first forced movement I have ever been through.”

Hafiez took it upon himself to keep the memory of the martyrs of the fights for freedom, peace, and justice. Every January, he exhibits paintings that remind the public of the stories of resistance. He has repeated such exhibitions in Sudan over 18 times, both solo and collaborative. Earlier this year, his black and white paintings were shown at the newly established Sudanese gallery in Nairobi, Kemet, the old name describing Sudan and Egypt during the pharaonic period. As a displaced person, Hafiez’s resilience in organising his iconic exhibition in Nairobi illustrates his commitment and passion to the cause. For Hafiez, someone with far more lived experience and familiarity with Kenya than the younger artists, settling into Nairobi elicits a different type of introspection. “We cannot deny the inherited traumas deep within us that were a result of the segregative and racist cultures of Sudan,” he says. “Social classes in Sudan are hierarchies of skin colour, and for the Sudanese people that arrived in Kenya, a country with a majority of dark-skinned people, there’s a challenge for them to overcome this downward view of people with darker skin. They must learn that the world is bigger than whatever beliefs were forced on them when they lived in Sudan.”

The relationship we have now as cultural practitioners who met again in exile is far more personal than it ever was. We share a deep trauma and a general concern that automatically breaks the formal and professional barriers. We also share an aggressively active survival instinct that sometimes hinders us from being as collective as we used to be or as we would like to be. The urgency of survival, however, does not diminish the impact of the shared trauma; it shapes the paths taken by individuals seeking refuge, as demonstrated by the journey of the three artists I interviewed for this text.

As the war drags on, we all wonder about the future and whether we must accept Kenya as our new home. Most of the network of Sudanese people in exile respond negatively when asked whether they would return if the war stopped today. The main reason for their answer is the lack of trust that has formed between them and Sudan as a space and a system. The love and longing are probably everlasting, but what does it take for those in exile to consider returning?

From a roundtable discussion, (left to right) Sudanese-French painter Hassan Musa, art critic Dr. Mohammed Abdelrahman Hassan, and painter Issam Hafiez. Picture taken February 2023 during Hafiez’s solo exhibition at Downtown Gallery, two months before the war. Photo: Rahiem Shadad