L to R: Aija Svensson and Rebecca Simons photographed by Jani Lappalainen

Hanna Linnove has always talked about her life openly. As a photography artist, it has been a natural choice for her to turn the camera on herself and her daily life. With empathy, she shows life experiences in her work that most of us go through at some point in our lives, like a breakup or having an eating disorder.

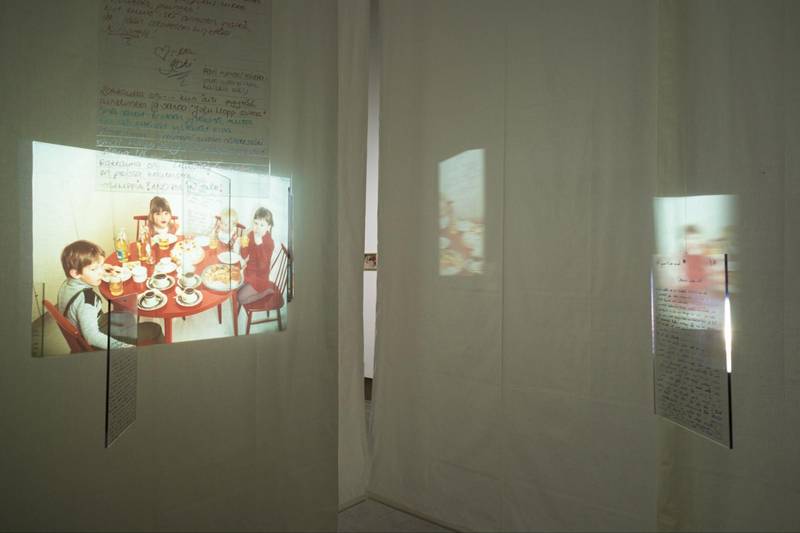

Rebecca Simons and Aija Svensson shed light on the complex dynamics of domestic violence and sexual abuse in close relationships and their impact on individuals and families in Past Uncovered, shown at Hippolyte in February-March 2025. The exhibition intertwines personal narratives with broader social themes, aiming to spark conversations about domestic violence and its lasting impact. Using a mix of documentary and symbolic approaches, the exhibition offers a visual and auditory journey through different perspectives on navigating trauma. The viewer confronts their individual existence, attempting to control the given moment by choosing a place to sit on a sofa to protect themselves. Viewers can identify with family photo album pictures from the summer cottage that have been layered using stories, glass, reflections and bruises. Torn and cut photographs tell us about frustrations that are both revealed and concealed. The exhibition features looped videos where letters from both the abuser and the abused are read aloud, allowing viewers to take their time to absorb the effect of this subject. By speaking about taboos, we strip them of their power.

At its core, Past Uncovered is a dialogue between the two artists. Rebecca confronts the sexual abuse within her family through letters to her late grandfather, while Aija responds to a lost letter her mother wrote to her daughters before her passing. Their stories unfold through photographs, video installations, archival footage, and a soundscape by composer Viljam Nybacka, weaving together memory, absence, and resilience. The artists invite reflection, healing, and open discussion on an often-silenced issue.

HANNA: When and how did you decide to work on a project that sparks conversation about domestic violence and its consequences?

REBECCA: During a visit to my grandfather’s home in Helsinki in 2009, I intended to document his memories of World War II, but he started asking inappropriate questions about my personal life, moving too close and making remarks that crossed the lines of familial relationships. “If you like someone, you like someone,” he said. He mentioned my cousin in passing, and I suddenly recalled that she had stopped visiting him years ago. When I later confided in my mother, she reached out to her siblings, and I did the same with my cousins. Through these conversations, three of my cousins revealed that they had been abused by him when they were children.

It took years of processing, conversations, and reflection before I could begin making work about this. By 2016, a police investigation had started, and I saw how differently each family member coped with the weight of this history. That divergence – how people carry, conceal, or confront trauma – became the heart of my project, and I felt the urge to do something with it. Not right away, maybe, but after having conversations with family. Then, it just became this monster project that I have been working on since then. It has also led to a lot of collaborations with other artists, psychologists, and institutes, so it has gained a lot of different forms.

AIJA: I spoke to a few therapists, and I just felt like, oh, I can’t get anything out of this. So, I started using photography to understand and investigate my feelings, but it became more significant. Because you can take a step back and observe the photos you have taken, it feels like, okay, maybe this is worth telling other people.

Aija Svensson, Do not cover, 2020. Photo: Matteo Parrotto

My background is with an alcoholic family, and this is a subject I deal with in my projects as well. I understand why my father became an alcoholic based on the generational pain. My grandmother always told me not to tell a soul what was happening in our home. Luckily, I never cared about the commandments. Seeing pictures from your childhood when you spent time with your grandparents during the summer brings up these memories. My grandmother was strongly worried about social status and how it looked outside. When it comes to shame, part of it is learned, and I think it includes intense guilt. I don’t want to believe that people are born guilty just because they found themselves in a problematic family. How do you feel about the shame passed down through generations, and how do you think it impacts individuals and families?

RS: It was quite difficult for some family members because they were scared about what would happen when this came out, and people who didn’t know about it would react, especially some distant relatives. When my grandfather (the perpetrator in our family) passed away, it became easier to talk about it. Although there were mixed feelings among us. Some of our family members were still more attached to him and didn’t want to see him as their father, who was also, in their eyes, a good person. This is also what I tried to bring out in the work, the conflicting ways of dealing with it within the family, where, in the beginning, I was… I think it’s quite judgmental. I felt like I wanted to just scream from the roof and say, HE’S AN ASSHOLE AND WE SHOULD JUST ALL SEE IT. But then, I also became more humbled through all those discussions. It’s hard to say or even think… No! I cannot say it like that… I wanted to say it’s also okay to love maybe someone who did something terrible, but I don’t feel that. I think one has to respect that everyone deals with things in their own way. I clearly notice that when you go out with stories like this, it takes away a lot of shame and helps other people to talk about similar situations and things they have been through. And that’s the beautiful thing about sharing personal stories like this.

AS: We never talked about what happened in our family. And I was blaming my mother for it. I was thinking: Why did she choose all these men who were narcissists and violent people? I couldn’t understand. I still can’t understand because it’s a choice you make. After my mother passed, my relatives started to open up to me about what had happened and what was behind the behavior. During the war, my grandpa had PTSD, and he became an alcoholic and a very mean and violent person. So, all that affected him. It’s a generational thing that you hold on to, and then it just goes on and on and on and on. I wanted to do this work, partly for my kids, because I am a mother. I’ve been thinking a lot about shame. Because this is a family thing. During the time I worked on the project, I used to listen to Märta Tikkanen’s late radio show, where she read letters that troubled listeners could send to the program with her friend. And she would always say, “The more shame you have, the more you have to talk about it.” That was encouraging.

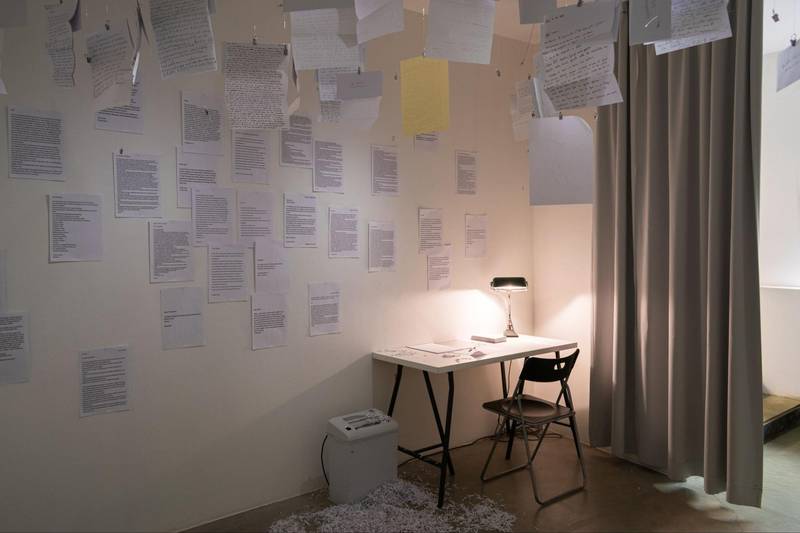

Installation view from Past Uncovered at the Photographic Gallery Hippolyte. Photo: Matteo Parrotto

Art is the right way to talk about taboos and shame. In photo and video art, there’s reality in front of your eyes, yet you speak about things behind the corner, out of the framed picture. Letters are more direct. In my work, I use abstract photos of alcohol to represent alcoholism, and I think I saw this symbolism in your works with glass that reminded me of frozen liquid.

RS: This is a level of interpretation. Like you said, you saw the image in the glass. You know, you might see something else. You can use these symbolic strategies and leave room for viewers to fill in parts of it themselves. I’m interested in different ways of interpretation. You can spell out things or leave more room for the viewer to fill in gaps. In my more documentary-format work, there is a more straightforward narrative, even though I also experiment with jumping between storylines and in time to confuse the audience intentionally. This is to resemble how we, as family members, were also confused in how to relate to the person who is both a loved one and a perpetrator, not either or but both at the same time.

In my newer work (the resins), I work more intuitively with my emotions, dissecting, preserving and reconstructing archive material that I fix through the resin. Here, the storytelling is less obvious, but the context given by the other work and in this case the exhibition Past Uncovered leads the audience to look at it in a certain way. In this case, the otherwise innocent-looking family photos appear more guilty.

The fact that you don’t spell out your whole story can work like that, even though pictures are documentation-based. In resin pieces, the process felt more intuitive and less about storytelling, focusing on reactions rather than precisely expressing what I wanted to say. In these pieces, I have worked more intuitively with my emotions, dissecting, preserving and reconstructing archive material that I fix through the resin. Here, the storytelling is less obvious, but the context given by the other work and, in this case, the exhibition Past Uncovered, leads the audience to look at it in a certain way. In this case, the otherwise innocent-looking family photos appear more guilty.

People connect to this work in different ways. Most of the reactions I get are related to people’s own stories; since I’m sharing something personal, I think they feel they can share something, too. This may be the best feedback, as I believe the work has a purpose. I had quite a few saying that they never talked about it, but that they now want to share with me that they also have been in similar situations (where a loved one has abused them). Or people who have shared it before but who agree about how important it is to be able to talk about it. These reactions also led me to create the writing corner in my exhibitions where people can write and share letters related to their stories.

One special meeting was with Diana Sundström, who shared that she had been abused by a relative and that she was never seen as a child, especially by the teachers. This led to a three-year collaboration where we organised workshops for over 100 teachers with Åbo Akademi and experts on seeing and meeting children who have been through traumatic experiences.

I once had a mother who realised she needed to inform her kids about abuse in a close relationship, went home to talk to them and then took them to the exhibition.

But I also had a man upset after seeing my film; in the conversation, he mentioned that the film reminded him of his father, who just passed away and how he missed him. This might be more surprising as it was unrelated to the abuse story.

Others appreciate visual interpretation more, looking more at how they have been told, the meaning of the material, the presentation, reflections in the space, etc. I think it’s also because you have already created a context around it. In this case, the exhibition provides the context of abuse in close relationships.

Detail view from Rebecca Simons’s work installed in the exhibition Past Uncovered at Photographic Gallery Hippolyte. Photo: Matteo Parrotto. © Rebecca Simons

What do you think about forgiveness, particularly in the context of processing trauma and abuse, and how does it relate to the act of creating and sharing art about those experiences?

AS: I was maybe bitter, or it was hard to understand. I don’t feel the need to forgive the abusers. I don’t want to carry the bitterness on because that ruins you. With this project, I haven’t forgiven my dad, and I never will, but more importantly, it was to forgive my mom. With the process of this work, I was able to forgive her.

The morally wrong acts might be hard to believe, so you intensely manipulate yourselves not to see those things so far that they might not be aware of their own actions.

RS: I started with a letter I wrote to my grandfather, asking if I could forgive him. I rewrote it for this exhibition. To better understand my emotions, I used the empty chair technique – borrowed from Gestalt Therapy – where you speak to an empty chair as if the person were present.

My grandfather had passed away at that point (2016), and by speaking out to the chair and recording this, I discovered a lot of things that I still wanted to tell him but never could. I reformulated my thoughts into a letter placed on his grave. This letter is the red line in my film, and I have been rewriting/updating it throughout the years when I exhibited this work. In this exhibition, we created a sound installation with Aija based on two letters, one that she wrote to her mother and the other from me to my grandfather. This was the first time I understood that I didn’t need to forgive him to move on. I realized it was not up to me to forgive him. It was up to him to forgive himself, which is not possible since he passed away. That realization felt like a relief; I didn’t have to carry the responsibility of forgiving him.

This idea of needing to forgive someone can be a burden. I don’t know if my grandfather was aware of his actions and, in that sense, if he would even be able to account for his actions, for he never admitted to the abuse that he inflicted on my cousins. The only thing he admitted to was putting us in a hypothetical sexual relationship. The rest was too big a taboo, you know, for himself. He somehow twisted what he did to my cousins in his mind. For example, he told me: “I remember when your cousin was little, and we were sitting in a car, and she said I love you, grandfather. What if I love you more than as a grandfather?” so in his twisted mind, he made it as if she had asked for it. As if he did her a favor. I guess there’s something so broken that this was a way for him to justify his actions.

Installation view from Past Uncovered. Photo: Matteo Parrotto

Our reality differs from one another. Still, there are surprisingly many among us who share the same kind of normality. What type of feedback have you received from the audience?

RS: I showed this work in a few European countries, and you can see that the interpretations of the work varied considerably between countries. In Italy, for example, based on conversations held with visitors and participants of workshops, I got the idea that families in Italy are generally closer, and therefore, the taboo is bigger. Abuse in family relations happens, unfortunately, more than is reported. Showing my family story helps others to talk about theirs. There was a woman in Italy, and she told me, “I didn’t know that this was wrong. My grandfather did this to me, too.” She went through this experience her whole life. She was emotional: “Oh my God, now I see it.”

AS: The stories people tell you are sometimes really hard ones. But I knew when I came out with this work that I also needed to be prepared to hear these stories. I have also had feedback, “I don’t understand at all”, because they’ve had such a great childhood. I’m happy for them! It’s great, and they can still appreciate the pictures. Like, “That’s a beautiful photo that reminds me of my summer cabin.”

Letters from the past © Rebecca Simons

Do not cover © Aija Svensson

There’s this unspoken understanding between people from similar backgrounds – a shared recognition of generational histories and inherited pain. Often, those who become abusers carry unresolved trauma from their childhoods. There’s always a history of people passed on from generation to generation. Yet society teaches us to stay silent, out of shame or fear of judgment. Today, however, we’re living in a time when people are beginning to call out the past and break that silence. While criminal behaviour must be addressed, I wonder if we can also approach abusers with a degree of understanding, rather than only condemnation. Speaking up about these experiences might not just protect others – it could also offer a chance for abusers to get the help they need. Could that be a way to end the generational cycle finally?

RS: I’m also in a collective with twenty other artists, and they are working around sexual abuse. The name of the collective is SAAC (Sexually Abused Artist Collective) Amsterdam. Almost all of them have been abused before the age of 18. What I hear from our discussions is that you recognize each other. You feel understood without having to explain.

I cannot forgive the actions of abusers because if you’re an adult and you abuse little children because you are traumatised yourself, it can’t be justified in any way. By creating this project, I feel we, the women in the family, are taking the power back. It’s not the abuser controlling what we can and cannot say. That is an important feeling for me.

AS: I’m with Rebecca on this; the actions are unjustified, and I could never understand them. I realize alcohol and drugs play a significant role in enabling sexual and domestic violence if the thoughts already exist in the abusers’ heads, though not always. There are many resources available for those struggling with addiction, and society is already quick to shame drug and alcohol use. But I believe we need more open conversations, more art, and even public campaigns that encourage people with violent or sexual thoughts about children to seek help before harm is done. Social media platforms must take greater responsibility, and parents need to be more aware of what their children are exposed to on YouTube, TikTok, and so on. We now understand far more about the long-term effects of trauma, like PTSD. With everything happening in the world today, I sincerely hope people seek help before they begin to pass their pain on to others. I genuinely believe speaking out can make a difference – otherwise, I wouldn’t have shared my work with anyone.

Installation views from Past Uncovered. Photo: Matteo Parrotto