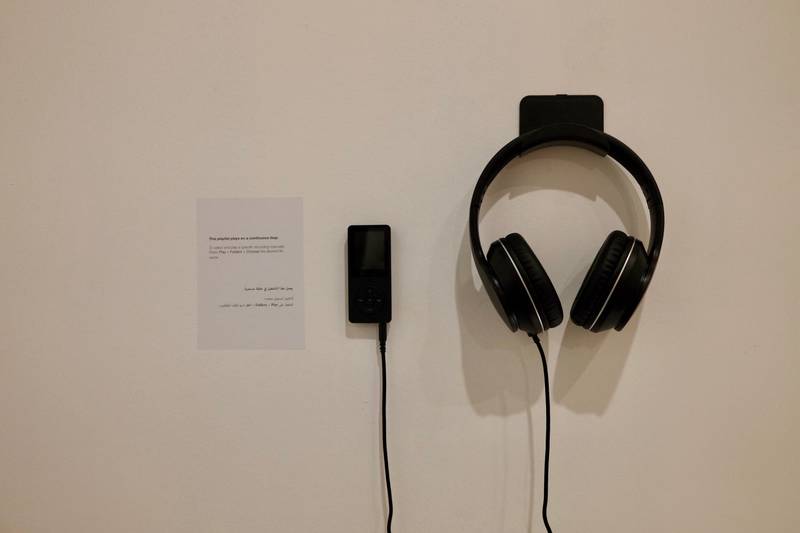

With the Feather in Our Throat, Jood AlThukair, 2025, Photo by Diana Smykova

Fatima AlJarman is a writer, researcher, and cultural practitioner based between the UAE and New York City. She is the founding editor-in-chief of Unootha and a writing residency co-director + public programs co-ordinator at Bayt AlMamzar.

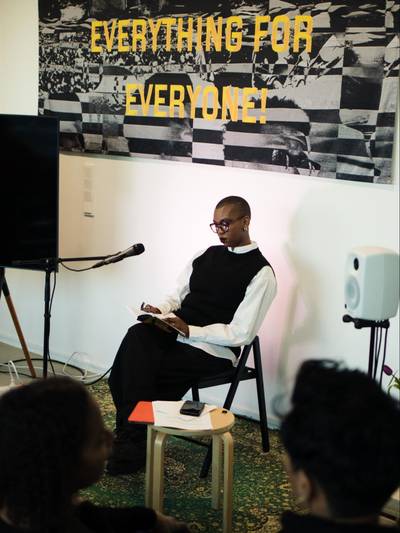

“The archive is first the law of what can be said,” writes Michel Foucault in The Archaeology of Knowledge; if an archive necessarily legislates what can be said, then it must subsequently determine what cannot. What then, leads an artist like Jood AlThukair to make an anti-archive? Jood is a writer and researcher from Riyadh, a Rhodes Scholar (2022) with an MSt in Comparative Literature and Critical Translation from the University of Oxford. Most importantly—at least to me—she is a dear friend and collaborator. During her three-month residency at Misk Art Institute’s Masaha, Jood constructed and weaved With the Feather in Our Throat, a living, tangible, material anti-archive of women in Riyadh, one that I was able to touch, feel, and listen to during the open-studios showcase on July 6th.

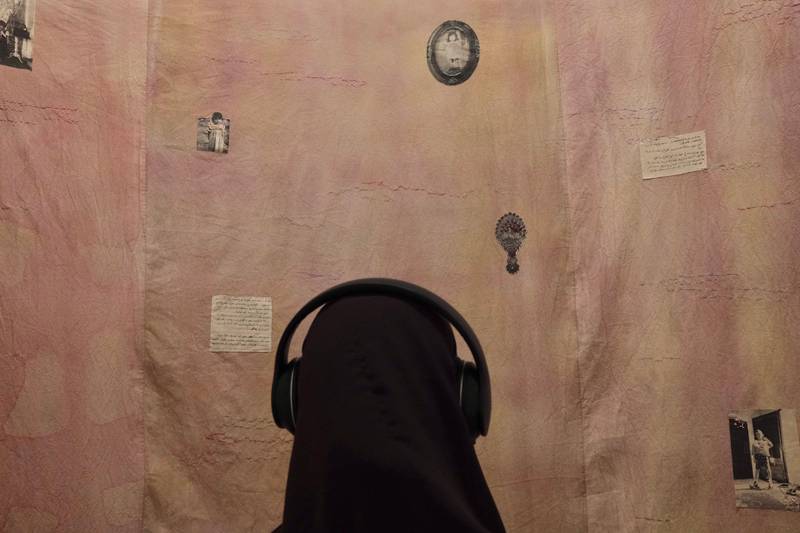

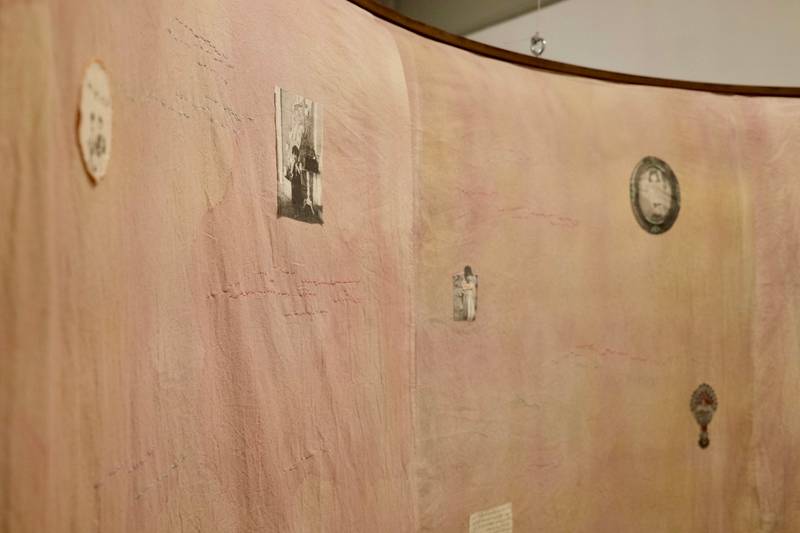

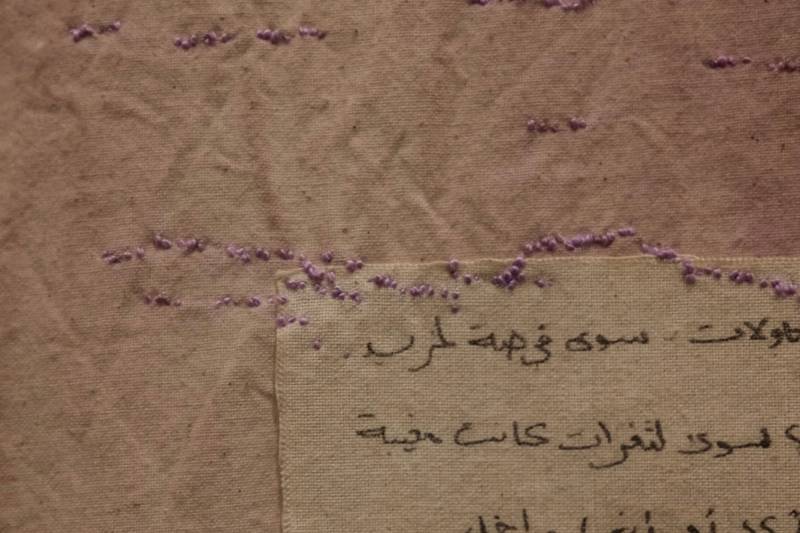

Born out of interviews conducted within her studio space, the archive itself lives across three mediums: the physical, the oral, and the written. In Jood’s studio, a 2.5-meter naturally-dyed tapestry is hung across a semi-circular beam, enclosing the innermost wall of the studio space. The tapestry faces away from the door, towards the wall, creating a separation between public and private. Two headphones and cushions are positioned for guests to listen to recordings of nine interviews, with zines featuring a selection of the conversations nestled between them. Wholly, you are enclosed within stories of bright childhoods and maternal connections as well as those of sudden illness and forced migration. The resonance that appeared to echo amongst all stories, however, was a yearning for belonging.

FATIMA: Where did the idea for With the Feather in Our Throat come from? Does it build on past work and research? Or is this your first endeavor into weaving what you describe as a “living archive”? Could you also elaborate on what the title With the Feather in Our Throat means to you?

JOOD: I’ll start with your last question first, only because its backstory is what led us here. Earlier this year, my Southern African friend, Bomikazi, ululated at a graduation she was attending in Oxford. One thing about Oxford is its weirdly cultish ceremony practices. To express joy, you may only clap. Hooting and whistling can never happen—I’m not sure if it’s prohibited, but it wouldn’t surprise me if so. It was also a time when I was creatively blocked, but witnessing this flickered something in me. Naturally, I had to write a poem about it! One of the lines read: “…the sun tears at the seams & pours feathers down / my throat.” This was in reference to encountering the archives at Oxford for the first time, and with that I entered a deep sense of disillusionment.

My master’s dissertation attempted to create an anti-archive for a ‘new ecology’ of Najd, where I come from, which is Central Saudi. Like many others, I was exhausted by the lazy interpretations of our landscape. When you mention Saudi Arabia, people always think of an empty hot desert, which isn’t always the case. I was annoyed by the concept of emptiness the most. What do you mean a living ecology is empty?

This project was my first real-life experience with living public-facing archives. Previously, I was focused on family archives with oral histories transmitted by my grandparents or my family circle in general.

I think from that point on, I was obsessed with the idea of the anti-archive, or the counter-archive as some may call it, so I knew I had to gather everything that I knew and shatter it. Every document that I had, I wanted to hold it and gouge its ugliness.

Can you tell me more about the disillusionment you experienced at Oxford? What led you to resist the archive?

Oxford loves saying that they have a rich archive [of the Middle East]. So I go to the Middle East Center, and it’s a whole security process of entering the archive, as with most archives.

Security, like, a checkpoint?

Literal checkpoint! And when I pass that checkpoint, I go to the archivist and ask, “Where’s the Khaleej section?” And it ends up being a slim file.

I open it, and come across developed film strips that mean nothing. They’re just vague pictures of the desert. I’m not looking at anything. The first time I met my great-grandfather was in one of these pictures, one that I wasn’t allowed to photograph. It felt very alien to me, like I was looking at him from the white gaze, even though we look alike.

With all this, the anti-archive isn’t meant to prove anything to anyone, especially not them. I was mostly interested in opening the gate and letting ourselves in.

I’m also in the horrible depths of the academic world. From your perspective, do you think an archive is necessarily violent and restrictive?

Generally? The archive is almost tyrannical. It’s cold. It’s violent. It’s painful. I feel like people often discredit the archive or don’t give it much thought here, but they don’t know that it’s the powerhouse of our collective memory and what we know of the world.

How do you think we can counter its violence? Do you think the countering happens when we call it the “anti-archive” or “counter-archive”? Or do you think it happens through a new process entirely?

I don’t want to say these projects are a response to the violent archive for me, but it’s also being idealistic to say they aren’t. I’m definitely aware of the violence or the violent foreground, but I’m not interested in making it the impetus for new knowledge transmission or for new projects.

With the Feather in Our Throat, Jood AlThukair, 2025, Photo by Diana Smykova

Tell me why women in Riyadh. And was your focus always women?

The Archive (capital “A”) fundamentally existed because historically, someone was documenting the present, which right now I think no one really is. There is an article I keep reading called The Spam of the Earth. Hito Steyerl argues that there’s so much junk on the internet, spam that’s taking over the earth—photos, WhatsApp voice notes, and memes. We send emojis, we send stickers, but there’s not much substance. So that’s not a national archive, per se. I kept wondering if there’s anyone documenting nowness, and I don’t claim that I am, but I wanted to contribute to that and create an archive that documents the present.

Who are the women in the archives? We are given a glimpse through the audio work and zines, but the tapestry—its careful yellows and pinks—reveals so many more conversations that we are not privy to.

I ended up interviewing about 70 women within 5 weeks, and did so through an open-call I shared on my Instagram with calendar appointments. I wanted to create portraits we don’t often see (or include) in the narrative, but part of me was worried that was unattainable. Social media callouts can either hit the mark or miss it completely, but I was very, very lucky to host people from backgrounds I never anticipated. At the beginning, some would ask if this was only dedicated to Saudis, which not only defeats the purpose but would make it an obviously exclusionary project.

These women, my collaborators, would come into my studio at the scheduled time, almost like a doctor’s appointment, carrying huge bags of pictures, certificates, awards, and stuffed animals for me to scan. It’s interesting because I wanted this to be an anti-nostalgic project fit for an anti-archive, and I said this to many of my collaborators before we started our session. For an anti-archive of the present, it matters that we recognize nostalgia as a facilitator for giving the past a false sense of utopia. But this ended up being such a glaring issue.

In some interviews, I realized I couldn’t expect to detach from nostalgia when they’re from an ethnic minority and seeking refuge in Riyadh, for example. It’s unrealistic to call it an anti-nostalgic anti-archive. These are stories of real women, women who’ve dedicated an hour of their day just to talk to me. One of my collaborators was Khadija, an immigrant aspiring fashion designer, who had to leave her PhD course after finding out she’s pregnant. This meant moving to Riyadh with her husband and becoming a housewife. The interview we shared was not only an escape but also an essential conversation for her to figure out exactly what she needed to do with her life. What to do with this kid who cries all the time and can’t handle her absence for five minutes. It feels ridiculous to even ask them to avoid nostalgia, not when their memories provide them with very real reprieve and comfort.

I think it scares me as a researcher to make all these claims, and then you do the fieldwork and find out it’s not as easy as you thought; you can’t put humans into boxes, and you certainly can’t enforce any of these notions onto them.

How would you frame the interviews then? So you can capture an expansive portrait of your collaborators while avoiding constraints?

The first question I asked was: introduce yourself in the same way you would to a stranger. That’s where they pause and wonder, ‘How do we introduce ourselves? Based on who we really are or what we do in our careers?’ So much introspection happens from there. We’d have these initial moments of silence and nervousness that come when there’s a microphone on your chest. So I’d assure them to take their time with the first question, and from that, I’m going to be able to ask more from what they shared.

During my first interview, I was nervous after doing the literature, reading about Saudi women as if I’m not a Saudi woman myself. It was ingrained that Saudi women were timid and shy, and you’d need more than one interview for her to give you that ‘golden nugget.’ But that wasn’t the case. I never needed to look at the document with pre-planned questions—the dam always broke.

A lot of them thought that this was a social experiment. A lot of them also had just moved into the city; they signed up because they wanted a space for community. What’s beautiful now is that they managed to not only keep in touch with me after the showcase but also meet so many other collaborators that it ended up being a literal space for connection and community-building. It’s such a pinch-me moment!

What’s fascinating is that I think only 30% of my collaborators were Saudi girls born in Riyadh. This opens up another list of questions as to why there’s little interaction from that demographic, because it’s noticeable how the majority of collaborators had recently moved to Riyadh or were part of other minority groups. Of course, each conversation was completely unique to its owner, but there were moments in my head where I thought, ‘Oh, she would make such great friends with this person’ [another collaborator].

I’ve also had disparate age groups in the archive, but the most common was from 26-35. These were working women who either had just finished their shift or took the day off to take part in this, which is crazy to even think about! You know, they always say Riyadh is a huge city, but more often we’d find mutual connections we didn’t know of until we had the conversation. I think it’s so easy to make these conversations; it’s just that there’s rarely any comfortable space to facilitate them.

Does the anti-archive challenge any existing preconceptions of Riyadh, perhaps some that you unknowingly possessed yourself?

Did it change my perspective of Riyadh? No, it changed my perspective of its people, for sure. For the first time, I immersed myself in the larger social fabric without a mother figure guiding me. You usually enter these semi-formal settings with a matriarch, like in a wedding, right? But for this project, I had to carry all the socializing independently. I’ve had women my grandmother’s age talk about childhood trauma. In any other context, I’d be pouring her coffee and sitting on the outskirts of the majlis.

As for the anti-archive challenging preconceptions of Riyadh, I don’t know if that’s something I’m interested in. I know exactly who we are and what Riyadh is, and again, I’m exhausted by the notion of making bigots the impetus for proving we’re human. Perhaps as a teen, I had much more energy, but now I think a project like this should speak for itself. I’ve had visitors who don’t speak Arabic insist on playing the Arabic audios, and many of them started crying. Others saw that most of it is in Arabic, or by women, or whatever, and they take a peek and leave. That’s when I know the anti-archive rejected them, and that’s what it should be: entered on its own terms. You won’t be able to access it until you respect it.

Something I still think about is what made this small studio so comfortable for stretching boundaries. There, we so easily delved into conversations about violence, Blackness, exile, miscarriage, and menopause. But also dreams, prayers, and secrets only shared with me and my four walls. This wouldn’t happen anywhere else, especially not the first time meeting someone. If anything, I was overjoyed to have the opportunity to be welcomed into the lives of women in Riyadh. A city so big that it housed us all.

With the Feather in Our Throat, Jood AlThukair, 2025, Photo by Diana Smykova

We had previously discussed the gaps of the institutional archive, but does your living anti-archive include any gaps itself?

I don’t want to call this a seamless project, but I was incredibly lucky with how smooth it went. There’s usually a lot of pain when it comes to processing ideas, but I guess With the Feather in Our Throat wanted to show its face to the world. Having 30-minute to 1-hour conversations with women I’d just met was no easy feat, and it required so much energy and human attentiveness. With that said, I remember leaving the studio at 11 pm after a long workday and wondering if I’m biting off more than I can chew. Or if this anti-archive can be eternalized. Or whether it should enter the institution. I think I’ve come to understand that I’ll be forced to make compromises I’m not sure I’m willing to accept, not only for my sake but also for my collaborators’. I’m happy with keeping it the way it is and letting it travel independently.

Time is another issue because I’m juggling a full-time job, but another important limitation was language. Language failed me in so many ways. There were moments of emotion, there were moments of awkwardness, moments where we realize that’s where the story ends and they have more to witness; all moments that cannot be transcribed or recorded into the archive so seamlessly.

But then, when we talk about language, I’m thinking of my Kurdish collaborator, Hevi. She would have loved to have her interviews in Kurdish. I don’t speak Kurdish. Another collaborator—Sumayah—reflected on her Nigerian identity, and she’s sharing little raindrops of vocabulary, but it would have been entirely different if I understood Xhosa, the tribe that she’s from.

As a linguist and a literature kid, you’re always obsessed with language and how it can confine us, but also how it can save us. That was the biggest limitation that I faced.

There is certainly a necessary loss in attempting to capture and document. Things will always get lost in communication and expression. And it’s something we grieve and also something we must honor and respect because it’s just part of the process. You’re not meant to fill all the gaps. One thing I noticed was that, although you mentioned conducting 70 interviews, not all 70 were included in the zine distributed at the installation. Was there a curatorial process behind that choice?

No, there was no curatorial process. Unfortunately, it was just an aspect of time; I was able to transcribe three interviews before the influx of the other interviews came in. Towards the end, I ran out of time, and it became difficult to continue transcribing and displaying all the interviews.

Ultimately, I want to display them at The Khaleeji Women’s Library and Archive (KWLA). KWLA is a project that I’m currently building the foundations of, and that is to make archives and libraries accessible for people, where you are able to both interact and also include yourself in the narrative. But of course, I would love for With the Feather in Our Throat to travel elsewhere [as it is].

The plan and the dream are to keep transcribing now, post-residency. Each one of these stories deserves to be brought to light, and it would be an injustice if I let them collect dust in my virtual drawer of a laptop. There are plenty more portraits that need to be finished. The work will continue and expand and disseminate, as an archive does.

With the Feather in Our Throat, Jood AlThukair, 2025, Photo by Diana Smykova