Painting by Hafsa Mahamed

Mariam Osman is an educator with a master’s degree in intercultural Education, and minors in English Literature and Art Education from the University of Oulu. She is currently working in the field(s) of refugee and youth education and employment. Her interests included art, design, and the processes of knowledge acquisition.

The Somali diasporic identity has long been shaped by survival, but now, generations in, new opportunities and paths have opened for greater choices. When we discuss the notion of art and artistic practices in Somali culture and its subsequent reengagement by today’s youth seeking connection to their culture, it’s imperative to shortly map the circumstances. It is tempting, especially in Finland, to group all minority concerns and conditions into one generalizable diagnosis; to assume that what ails one due to this reason, ails the other for the exact same one.

Somali migration to Finland began in the 1990s; and though not limited to Western countries, the outbreak of the civil war led to communities being established across the globe. Amidst these ruptures, families brought along whatever they could: letters, photographs and cassette tapes for safe keeping. The mechanisms to make and document were left behind, in this new world, there didn’t exist the luxury of navel-gazing. If you ask the average Somali diaspora to tell you about how art manifests in our histories, we’d often speak of nomadic1 and oral traditions.2 I’ve recently been trying to redefine the temporality of these modalities for myself. Nomadic and oral practices are widely thought to produce work that eventually would be lost to time, existing in transient forms. According to Ali Jimale Ahmed, “the Somali oral tradition like any other oral tradition extols the virtues of memory. And memory presupposes two things: the existence of a pool of memorizers and secondly, a constant repetition of the “word” for its survival." I realized that as long as we had our elders, back home and in the diaspora, our history would always exist in a generative realm. Displacement causes generational gaps in cultural knowledge, yet it will always be ready to spring up repeatedly in reimagined ways.

In the summer, I sat down on multiple occasions with four youth in the Helsinki area, all engaging with their own artistic practices both professionally and personally. Through our various meetings and discussions, we unpacked the knotty realities of following your own path and navigating an existence where you are pulled between parental expectations to manifest outcomes and, more importantly, structural barriers. I spoke with Saara Abdi, a third-year student at Aalto University, studying Design. Hafsa Mahamed, a visual artist in her first year of studying Art Education at Aalto University. Abdihamid Muhumed, who recently published a poetry book titled “The Broken Letters” with support from Arkadia International Bookstore and lastly, Ibrahim Mohamoud, a student at Aalto University studying engineering but with strong hopes from a young age to pursue film. They represent the growing second-generation that is unafraid to dream beyond the constraints of a society that has a preconceived idea of what their roles should be.

The Path to Dreaming

For various youth, many of whom have never been to Somalia, creative work becomes a way to explore what it means to be Somali in Finland. Inspired by a two-week TET, in which she job shadowed at Kiasma in an attempt to challenge herself and do something different, Saara spoke about this being the first encounter with the institutional side of the art world that shaped her idea of what was possible. Expecting a simple experience, she instead discovered large-scale works by Mona Hatoum and Choi Jeong Hwa that transformed her understanding of what art could be and who could create it. She also realized she didn’t have to be a traditional painter to participate—the art world included curators, technicians, and educators.

It’s important to Hafsa that her work speaks to other Somalis and community members, not by way of becoming a spokesperson, but by making sure curators accurately reflect the religious and cultural intention of the works while circumventing narrative binaries.

Similarly, Hafsa mentioned a related encounter that highlighted this interconnectedness of experiences. It was at the Amos Rex generation 2020 exhibition, the year that Saara was featured, that her friend turned to her and said that she would have her art displayed there one day. Next year, her work exploring themes of abstractness and facelessness connected to Islamic drawing practices will be on display at Amos Rex’s Generation 2026 exhibition. It’s important to Hafsa that her work speaks to other Somalis and community members, not by way of becoming a spokesperson, but by making sure curators accurately reflect the religious and cultural intention of the works while circumventing narrative binaries.

Having grown up together, it was Saara who encouraged Ibrahim to pursue applying to film school or a design program like hers, since he was already applying to Aalto. Yet he faced the barrier of familial pressure, compounded by the gendered expectations surrounding more experimental fields that were seen as unlikely to provide stability. Today, Ibrahim is working on film and campaign projects with his friends, alongside acting and modeling endeavors. Having attended a media-focused high school as a timid kid, the experience gave him the chance to step out of his bubble and expand his horizons.

Abdihamid’s work deals with piecing together the idea and meaning of somalinimo,3 what his parents went through to get here (stories of which were communicated to him through proverbs), and how much of his art is a conduit to parse through this identity. He recalls a fourth-grade poem prompt about love as his artistic awakening; today he dedicates his debut poetry book to the “dreamers, the mourners, and the ones still searching for home in the echoes of the past.”

Saara Abdi, Photo: Mariam Osman

Hafsa Mahamed, Photo: Mariam Osman

Implications of Career Guidance and Counselling

In Finland, students have the right to receive counseling toward the end of comprehensive education. The main aim is to support them in pursuing aspirations that align with their educational trajectories and expectations. However, controversy persists around the guidance of immigrant students, especially those who have spent their entire lives in the Finnish school system. For Somali students, career guidance carries particular weight, as many are the first in their families to navigate not only the education system but also wider society. Somali students display a general apathy toward counseling owing to their negative experiences. Despite their high aspirations to pursue academic tracks4 or explore broader ambitions, they are frequently steered instead toward vocational paths oriented toward labour market readiness.

Saara had good grades, involved parents and a plan for her future, so she felt it was hard for teachers to tell her otherwise. Even though she was not receiving much feedback from school staff, she got the general feeling that the environment was not necessarily one that wanted to see her succeed.

When I asked Ibrahim about his experience, he explained that, because of the immigrant makeup of his school, he and his friends were already being advised to pursue vocational tracks as early as 9th grade. Yet coming from a family where high school was considered the only option—and having set further educational goals from a young age—he recalled that his counselors provided ample information about applying to engineering or health professions. The only advice he received about artistic fields, however, was that employment would be difficult. In the end, he credits his older sister and siblings as his true counselors.

Saara, on the other hand, rarely went to counseling, though she had no shortage of stories from friends and family about their experiences. Her family also heavily encouraged, even mandated, her academic pursuits. She received counseling from her parents, especially her father, who himself had a long career as an economist and had also previously researched the education outcomes of immigrant youth in Finland. Saara had good grades, involved parents and a plan for her future, so she felt it was hard for teachers to tell her otherwise. Even though she was not receiving much feedback from school staff, she got the general feeling that the environment was not necessarily one that wanted to see her succeed.

When it came to Hafsa, she was happy that she had not received any counselling from her school. She acknowledges that between poor guidance and no guidance at all, she may have been ironically lucky for receiving the latter. Despite having supportive teachers who were able to identify her artistic talents, she took their notice as a compliment and not as advice. It was her move away from home and some time on her own that was the catalyst for applying to school in the end.

The Finnish education system is often seen as a place where all students can pursue paths that match their abilities and motivations. Study counseling is meant to help young people not only understand their options but also figure out what paths are visible to them from where they stand, both individually and structurally.5 Yet in reality, many end up having to carve out their own space through trial and error, often turning to friends or older siblings who are navigating the system alongside them or have already gone through it, rather than relying on institutional guidance.

Competitive application processes to popular university majors are additional barriers to entry for immigrant students and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. With the rise of preparation courses, “valmennus kurssit,” starting as early as high school, students who are able to pay a large sum to be coached in private courses by professors have an advantage over those applying on their own. Taking a gap year after high school to work in a daycare, Saara saved up money and was able to secure a spot in a preparation course to help her apply to the design degree at Aalto. She relayed that on top of having to pay out of pocket, it was not a guarantee that you would secure a spot in the course. With her parents telling her to only apply once and then return to more practical career endeavors, she saw the course as an opportunity to strengthen her chances of admission.

Although she attended the course for only three weeks out of the one-year package, during that time she gained valuable insights into the three-part admissions process, which included preliminary assignments, intake assignments, and an interview. Saara noted that there were no other students of non-white origin in the prep course. She also recognized that some professors leading the sessions were employed by the university, even though the course was not affiliated with it. She was astonished that there was this whole other way of doing things that was not a norm in other communities—ways to get ahead if you had the means and knowledge to do so.

A large percentage of students who go to preparation courses are admitted into their desired degree programs. In an article by Helsingin Sanomat in 2019, 60% of admitted architecture students to Aalto University attended a preparation course by a company with a monopoly in the region.6 With course prices ranging from a few hundred euros to three thousand euros, the ethics of this advantage in destabilizing the “even” playing field in an education system that is lauded for its equality and fairness of access are interesting. In 2023, Aalto University announced that it would be attempting to curb preparation course advantages, particularly in the field of architecture, by rejecting those found to have used third-party assistance in their application process.7 The university did not outline how they would monitor this, but it is clear that under neoliberalism, higher education is no longer merit-based.

Language and Its Impacts on Creativity and Higher Education

According to the most recent PISA results on literacy in Finland, second-generation immigrant students perform poorly in academic settings, a pattern linked to both language proficiency and socioeconomic background.8 Despite being born in Finland and educated primarily in Finnish, many Somali students—along with other non-native groups—are placed in Finnish-as-a-second-language (S2) tracks on the assumption that speaking their mother tongue at home creates linguistic gaps. Yet while another home language may be present, this does not necessarily mean Somali youth are fluent in Somali, nor that they use it exclusively with one another in social settings. The assumption that Finnish-Somali youth possess greater bicultural fluency—the ability to move seamlessly between their heritage culture and Finnish society—also proves misleading.9 In reality, many struggle to fully integrate into mainstream Finnish culture, particularly in linguistic terms and in contexts requiring broader cultural competence compared to their native-born peers.

We discussed with the youth in this piece about the potential links between creative expression and linguistic ability. Many of them encountered the realization that there seemed to be a correlation between their lack of rigorous language schooling and its subsequent relation to difficulties in being able to express themselves both academically and in their art. In S2 classes, some reported missing the opportunity to engage in extended narrative writing, poetry, or interpretive literature studies like their peers. This track that was intended to bridge gaps in practice was acting as a glass ceiling, keeping them from accessing the mainstream curriculum that fosters higher-level creative and analytical competencies. S2 language tracks also posed a barrier to university entry, as universities required higher grades in S2 final exams compared to the native language final exam, a rule that was abolished around 2018.10

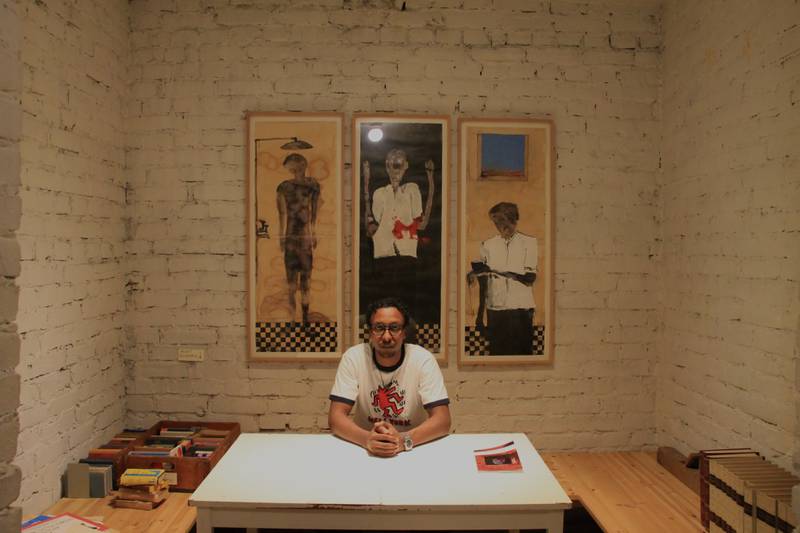

Abdihamid Muhumed, Photo: Mariam Osman

Ibrahim Mohamoud, Photo: Mariam Osman

The Importance of Practicality, or Integrating Other Passions

It was not lost on the five of us that there was a certain hesitancy—or perhaps a lack of belief—in following a singular road toward becoming an artist in a context where there was little external confirmation or assurance of success. Whether in the form of schooling, parental concerns, or any tangible proof that space in the industry was waiting to be filled, that validation was largely absent. Among everyone I spoke with, there was a kind of sage understanding, a wariness that artistry alone could not exist in isolation from pragmatism, especially for youth from collectivist cultures invested in securing the best possible futures for them. This is not to say the alternative meant pursuing something wholly undesirable, but rather finding ways to combine adjacent passions to strengthen their ability to continue along the artistic paths they desired.

I mulled over the idea of applying to school to study writing with Abdihamid, wondering if that was an option for him. He spoke of his ideas around what he called the Somali rejection of traditional schooling around art and how, as a people, we rarely seek to be folded into and patted on the back by establishments; our poetry tradition and modalities span a history that no curriculum or didactics here could replace. For him, contentment comes from charting his own course in his work; while that is more his personal domain, he is also passionate about academic routes and will be pursuing a degree in molecular biology this fall. In high school, Saara found a passion for entrepreneurship and completed all nine courses offered. Presently, she incorporates this passion into her university studies as a minor, and while it does not overlap heavily with her design studies, she finds that it supports her interests and strengthens her work prospects. Currently, she is working as a coordinator for HIAP – Helsinki International Artist Programme, while also writing her bachelor’s thesis on motivations, perception and barriers to youth participation in museum spaces in collaboration with Amos Rex.

Ibrahim conveyed repeated hope to study film, though he was aware of the limited study spots available in Finland; to him, being an engineer was equal parts a childhood dream at one point and a parental expectation. Presently, he is able to discern that having a fallback option, though he acknowledges that it interferes with his ability to concentrate on putting his all into his passions, is a fortunate thing as a young Somali man. For Hafsa, having worked as a substitute teacher, she believes that the education component of her studies might offset the difficulties of being an artist and allow her to inspire other children and act as a role model that she was lacking in school.

What emerges most clearly here is not personal limitation, but resilience: an insistence on reimagining art as both a personal and collective tool of belonging, expression, and survival. These stories illuminate the layered realities of Somali-Finnish youth striving to carve a place for themselves in Finland’s artistic and cultural spaces. Their journeys reveal both the immense creativity that exists within the community and the structural obstacles that persist in their paths. Their perseverance signals that the underrepresentation of Somali voices is not a reflection of lack of interest but of barriers that can and will be dismantled. As their presence grows, so too does the possibility of a cultural landscape that is not only more inclusive but also more honest about the histories, languages, and identities that it is made up of.