Photo of Nishtha Jain by Deepti Gupta

Ananya Parikh teaches film, literature and gender studies in Pune. She believes that the classroom is a place to begin conversations that link the world of ideas together with everyday lives of students and society. Her teaching and research interests are largely oriented to understanding and linking histories of cinema, especially alternative traditions of cinema including avant garde and documentary with questions of aesthetics, politics and contemporary theoretical concerns.

Nishtha Jain’s documentary films from early 2000s onwards have consistently addressed the intersections between the personal and the political in varying and relational manners. In her most recent work, Inquilab Di Kheti (Farming the Revolution, 2024), which is also her most ambitious, Nishtha traces the year-long farmers movement (2020-21) against the three unjust farm laws announced by the Indian Government in June 2020. Nishtha’s film opens up the everyday textures and rhythms of this massive and ultimately successful movement. The interview also attempts to locate the film both in the context of the movement as well as in the larger context of documentary traditions, formal aesthetics and the politics that inform Nishtha and her other films.

ANANYA: Inquilab Di Kheti is about an extremely crucial time and records a defining moment in India’s contemporary history, in relation to how the nation-state is imagining itself and its citizens in the 21st century. You were already an ally to the farmers movement, participating and involved in the spirit and the politics of the moment. At what stage did you decide to start filming what you were witness to? What were some decisions you had to take? What ideas informed the process when you started, and as you continued to be at the Delhi border and film over a year.

NISHTHA: We began filming within three days of the farmers’ arrival at the Delhi borders. In the beginning, research and filming happened simultaneously. We immersed ourselves in the vast movement, observing, learning and understanding. Thousands of farmers from different states were stationed at three to four Delhi borders. Their tractor-trailers extended for miles on the highways. There were at least 44 farm unions, and more kept joining. Each had its own leadership. The farm unions came together under the banner of Sankyut Kisan Morcha (SKM) or United Farmers Front. There were several stages from where the leaders made their speeches, and from where important information and instructions were disseminated. These were also used for cultural activities.

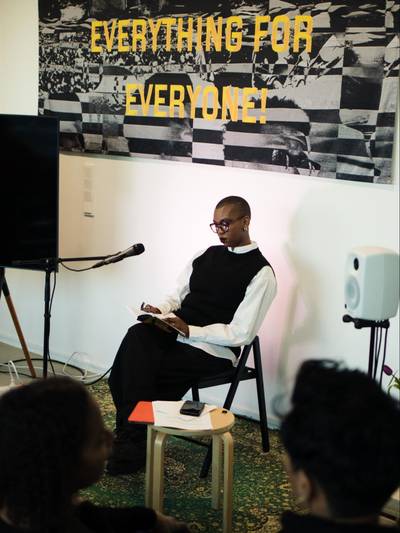

I knew the film would become a window to the poetic/cultural aspects of the movement. There were so many singers, poets, writers embedded in the movement. I went about recording their poetry, sharing their diary notes, or singing. And of course, filming the stage where speeches and songs were performed. The stage was a great source of learning.

Given the scale of the movement, the task of choosing our protagonists was tough. Additionally, we had no funding for ten months of the shooting. I could only afford to hire a small team. We had a basic camera and location sound set-up. I could not spread myself thin; I had to choose. Once I decided on the farm union and the leader to follow, the job of finding the protagonists followed from there. We needed our protagonists to be stationed at the border, and not coming and going. By late December 2020, we had fully committed to the film as we had connected with the farmers and leaders who would become the film’s central figures. However, documenting an ongoing protest, where each day’s outcome is unpredictable, posed several challenges. I had to do mental-scripting and planning all the time. There were some things I was sure of – I knew the film would become a window to the poetic/cultural aspects of the movement. There were so many singers, poets, writers embedded in the movement. I went about recording their poetry, sharing their diary notes, or singing. And of course, filming the stage where speeches and songs were performed. The stage was a great source of learning. The farmers movement in Panjab is not new and the speeches illuminated us about the histories. The tent-city felt like a university. The leaders (teachers) had people’s (students) attention. And they went about educating the farmers of their socio-political-economic-environmental context within which they are working, and how their very existence was threatened by the farm laws.

Also, the unpredictability was extremely high. The movement could have ended abruptly or continued indefinitely without any resolution. Filming such a dynamic subject was not only risky in terms of time and resources, but there were also concerns for the health of our crew members as the protests were happening during the Covid lockdown. What kept us inspired was the courage, resilience and resolve of the farmers. Their perseverance rubbed off on me. I could not stop filming even though it was my own savings that were being poured in. We filmed for 135 days in thirteen months! I’ve never filmed that long.

Photo by Randeep Maddoke

Documentary filmmaking has often been thought about as a process of recording, of archiving, and many documentary films become the archives of the present. This idea of the film operating as an archive runs across your work, not only in relation large moments/movements like the farmers movement in Inquilab Ki Kheti or workers in The Golden Thread, but also the everyday lives, the daily encounters that reveal something like in City of Photos (2004), or Family Album (2010). What does it mean for the filmmaker, then, to stand witness and to archive these histories while also locating themselves in the same? How do you engage with this process, this encounter?

With the passage of time, text, visual and audio material take on an archival quality, each bearing a timestamp. This awareness is particularly acute when documenting places, people on the cusp of extinction, as in City of Photos, which captures photo studios at the juncture of transition from analog to digital photography. The photo studios with backdrops and props were seeing their twilight days with the coming of digital photography and mobile phones. Similarly, in The Golden Thread, we documented the last vestiges of the centuries-old jute factories or jute factories at the cusp of moderinsation. Interestingly, very little visual archive of the Indian jute factories exist other than news reels of frequent conflicts between workers and management, or corporate films. This is the first time a camera entered the Indian jute factories to capture them as they are, without staging. The film is also an archive of the sounds of the old machines and looms which have all been replaced by electric machines. In Farming the Revolution, we are aware that we are documenting a historic moment. Unlike The Golden Thread, there were many photographers, videographers and filmmakers at the farmers protests. The challenge here was about the uniqueness of my take. Why another film? Do I have something unique to say about the protests? My creative interpretation of the actuality creates a subjective archive. One could however argue that there are no objective archives.

You make an important point about the (impossible) objectivity of the archives. Do you think that there is a burden often experienced by the documentary tradition/filmmakers about objectivity versus subjectivity? That they are constantly seeking a balance between the historical, material reality and the subjective, experiential perceptions of the same?

Given a distance of time, even fictional material becomes documentary, holding mirror to the reality of the time it was recorded in. From locations, costumes, to storytelling techniques, to acting and sartorial styles, to the politics of the film, both on screen and outside. Compared to fiction, documentary footage holds infinite archival value. But it’s always important to ask even as we watch news unfold, not just documentaries –who’s looking at who, and how much of the reality are we being shown.

My films are not reportage. But given that we are living in the times of fake news, it does become imperative to address this aspect especially in Farming the Revolution. During the year-long farmers protests, farmers struggled to establish their narrative against that of lapdog media which was painting them as terrorists and troublemakers. This was important to highlight in my film. And also, to let the viewers know that my film was focused on a particular farm union and a few leaders because it was impossible to make an overarching film about the huge protest. Neither did I have the means to cover the entire length and breadth of the protest, nor the luxury of time and money to turn my material into a docu-series. At some point in the future, I hope to. But I wanted to exploit the moment when people still had fresh memories of the movement and most importantly, reach the film to viewers outside India who may not have heard about the biggest and longest protest in the world because of the embargo on real news from India.

More than a burden, I feel a responsibility when I categorise my film as a documentary. I do feel a duty to adhere to a certain observed truth. Not to stage events because they suit the story-arch. I prefer to live with gaps in the story, an uneven quality. I prefer to include my questions even though they break the suspension of disbelief. For me, the camera is not a fly on the wall. The people on the screen are responding to me, or continuing to behave in a way despite the presence of the camera crew. I do feel I have a duty to convey the truth even if it makes my protagonists look weak (read human), or the story thin. Like in Gulabi Gang, we see one of its members –Husna turn hostile when her brother is accused of murder. She seeks help from the Gulabi Gang leaders but they refuse because they also have an image to protect. She feels that they have thrown her under the bus ignoring her unpaid work all these years. Hurt, she quits the group. While the inclusion of this incident undermines the concept of ‘pink revolution’, it also helps to ground the film in reality, and to once again reflect on how deep-rooted patriarchy is and how difficult it is to bring change. Also, to show human frailty and reflect on the role of fear, and in equal parts lure of power and money. I don’t like putting my protagonists on a pedestal, making heroes out of them by conveniently deleting certain aspects of their lives which could colour the picture differently. I’m comfortable with showing people as grey, not virtuous.

I feel that to falsely construct our protagonists as heroes by deleting their negative aspects only weakens the film. Embracing greys without losing one’s point of view, is my way. It doesn’t make for very popular filmmaking.

To me, an unwieldy reality is better than a neatly unfolding film. Such films are predictable and therefore boring but certainly more popular, and marketable. In The Golden Thread, I could have used the opportunity to give a platform to the Indian trade unions but the fact is that they have not been able to bring about a change in the working conditions and the wages of Indian workers. Their leaders are often compromised. While showing a strong trade union movement could have helped me make an inspirational film, it would have been a lie. But I witnessed the power of unions during the year-long farmers protests. And the union –BKU (Ekta Ugrahan) and its leadership – which I have highlighted in Farming the Revolution has not taken a day’s rest since the protests in Delhi got over. Their success in Delhi, and their work in the preceding years and after, is a shining testament to their remarkable leadership, unity and hard work. They are exceptional and a beacon of hope in this dark world. However, in the film, I don’t just paint with one brush, I also show the lean moments when the majority of the farmers left for their homes to harvest, or when the death toll was rising. I also give a glimpse of their internal differences. For example, how the people participating in the Republic Day parade, many of whom were not even farmers, walked into the devil’s trap by breaking into the Red Fort. Not that they committed any crime by hoisting the flags of their unions at the fort, but they did give an opportunity to the lapdog media to paint them as terrorists. I feel that to falsely construct our protagonists as heroes by deleting their negative aspects only weakens the film. Embracing greys without losing one’s point of view, is my way. It doesn’t make for very popular filmmaking.

Still from Farming the Revolution, cinematographer: Akash Basumatari

The title of the film Inquilab di Kheti, brings together so many threads – the history of farming in Punjab, and the Sikh communities’ deep engagement with the land and agriculture, the contentious issues of the farmers’ rights, which is the reason behind the protest, as well as the very idea of cultivating and nurturing the spirit of revolution which the film reflects. For me, the most striking aspect of the film was the recurring images of kneading and rolling the dough (I want to use the Hindi word belna here) and making rotis on open tawas, and the sense of community life and conversations surrounding that. There was something raw and beautiful about how those (amongst other images) connected with the larger politics of the movement and the film. I would love to understand how you are bringing these images and ideas together in the film.

In March 2021, four months into the farmers movement, I glimpsed the essence of my film, captured in its title: Inquilab di Kheti (Farming the Revolution). The farmers were cultivating a revolution, drawing on what they know best – farming. Their livelihood demands not just hard work, but patience and unwavering faith in the eventual harvest. And if the harvest fails, they start all over again. The farmers believed that they had already won; when their victory would be declared was just a matter of time, and they were mentally prepared to wait till such time. In this waiting period, daily activities, and hardships owing to vagaries of season become significant. They test the patience and resilience of the farmers. Other than attending the stage, cooking two meals daily occupied a big part of their day. The act of making rotis becomes an act of resistance and therefore the central theme of the film.

Still from Farming the Revolution, cinematographer: Akash Basumatari

Another question about the structure of the film. There is a moment in the film, where a voice over discusses the nature of struggle and the movement, comparing it to a river, which emerges with a great force at its source, and then flows apparently in gentle and calm manner as it follows a path. The film also has a similar narrative structure, a similar trajectory– from the opening sequences that bring together a few identifiable faces and locate them in this intense liveliness of the movement. The shots and frames are brimming with energy, there is music and crowds and a feeling of vigour, but as we spend more time with the farmers, and days pass, especially after the 26th of January, the film also becomes calmer, slower, letting us get a sense of time, of the waiting, of how revolution is equally about patience and fortitude. How did you conceive this trajectory and also does this narrative form allow you to comment on the nature of socio-political concerns themselves?

The most important thing to me was to give a sense of time. The protest at the Delhi borders lasted 13 months. During this time there were repeated activities – speeches, cooking, protests and a lot of waiting, months and months of waiting. How to create a sense of time and yet not make the film a tedious watch. One was to show the changing seasons, changes in farm activity, lengthy months of bitter winter, followed by heat waves, and monsoon. But also, to show the change of energy, pace and mood. Joginder Singh Ugrahan always gave a different, refreshing spin to the questions being asked. To the people saying the protest has gone on too long, he would say, ‘I wish it would go on for at least two years because then I would have my people’s full attention’. This is acknowledging the tent-city as an open university where farmers learnt from the speeches on stage about their own histories, and issues related to farming. They learnt from street plays, songs, and books. It was a transformative period for people where they had time to learn their own histories, read books, and learn from other artists. It was the same for me too. I learnt a lot from the speeches. So much that’s not in the books. At another time, and this is in the film, he reflects on the quieter months when there are fewer people at the borders. He uses the analogy of water being noisy when an unused tap is opened and then becoming quieter as its flow stabilizes. His ways of seeing the movement was so unique and refreshing, it also guided the film’s structure.

Photo by Nishtha Jain

Still from Farming the Revolution, cinematographer: Akash Basumatari

I was interested in ways in which the film brings together a number of characters, letting us get an idea of a larger collective and also an idea of a community. As a documentary filmmaker, who has also focused on an individual character or story, what led you to choose this style where you are simultaneously capturing a large struggle but also intimately focusing on some faces, and voices? How did you decide who to follow, how many and why?

I’ve made two character-driven documentaries, the rest all have multiple characters. The characters are not just human, they can be the city, a mill, a housing society, the elevator, or a housing society rooftop. How could I possibly make Farming the Revolution a character-driven film? If I did, it would be limiting and would require elaborate staging which is an absolute no-no for me. I had to show the collective, the coming together of farmers from different states, old and young, men and women, rich and poor, landed and landless. While it’s not easy to edit such disparate elements together, it requires a lot of editing experience; I have managed and succeeded since my very first film, City of Photos.

This brings me to the presence of women both in the movement and in your film, not only through the conversations with women but also through their presence. This also connects to many of your other films whether it is a single character in Lakshmi and Me or the Gulabi Gang. I think this is particularly important because we see women here as active bodies, unlike the commercial films where women are largely passive and are meant to be seen rather than “seeing” subjects.

Women were an equal part of the farmers protests. The film is showing the actuality; it’s not the feminist in me posturing or imposing my wishful thinking on the film. In fact, the biggest gathering of women in India took place on March 8, 2021 at Bahadurgarh border, organized by BKU (Ekta Ugrahan), in which Harinder Bindu, Parminder Kaur were prominent mobilisers… But we don’t see this scene in the film because it felt like tokenism. Instead, we see women during the normal course of the protest – organizing, mobilizing, giving speeches, cooking, driving a jeep etc. I don’t like to tailor selections in my film to tick politically correct boxes. Lakshmi and Me is about two women in a city, one a relatively privileged middle-class filmmaker, me and the other Lakshmi, a domestic worker. The film starts with me reflecting on our relationship, and the discomfort with the hierarchy between us, and whose roots are in social hierarchies at the intersection of class, caste, and gender. The film complicates the question of feminism in our deeply stratified society and turn the camera on myself. Who works for whom, what caste are they? This was my most difficult film. Similarly, in Gulabi Gang, while Sampat Pal is the founder-leader, the film shows other local leaders too. The decision not to focus on the leader met with some criticism but it was important for me to show them as a pressure group, exercising their influence on subjects related to other kinds of inequities.

The film also kept leading me back to the idea of communities, especially political solidarities. Towards the end of the film, during the speech and rally on the occasion of International Human Rights Day, there are references to other individuals and groups also fighting against the ongoing human and political rights violations by the state authorities. As someone who is part of these solidarities, how do you conceive the future role of filmmakers and artists in building these solidarities, especially against the backdrop of an adverse environment of both logistics, funding, lack of reaching larger audiences and the very real threat of physical harm?

In 2014, many Indian documentary filmmakers attempted to come together and register as a collective but we failed because of irreconcilable differences. We desperately need accreditation (press-cards) to be able to film in many situations where only press-card holders are allowed. Fortunately, my cinematographer had a press-affiliation and so we were able to film in places that were not open to non-press people or filmmakers. As a collective, we could definitely have been stronger but today, we are the least privileged, and least protected amongst the filmmaker community in India.

I prefer not to make films at all, than make films that are not aligned with my nature or worldview. I veer towards those themes or stories which will allow more therao, introspection and possibility of exploring other layers beyond the socio-political, while at the same time being universal and not esoteric.

The film has travelled to various places. I am interested in what were the responses to the film by different audiences, both domestic and international. I also know that the film was screened and seen by many of those who are a part of the film. What was the reaction of those who are a part of the movement that film documents?

The response to the film has been overwhelming. I think my best screening till date was at Dharamshala Film Festival where the audience was crying, cheering, laughing, whistling. It was difficult to believe it’s our film. I received the same overwhelming response in Morocco, Sheffield, London, South Korea, Sydney and Toronto. In Panjab, we screened the film in several cities. Most of the protagonists of the film have watched it. Joginder Singh Ugrahan spoke immediately after watching the film and I was impressed by his keen observation about the technique of creative documentary. Another leader said, ‘We used to see this girl shooting with a small camera and a small team, but we didn’t realise she’s making cinema.’ There were many complaints, too, about things or events or people that were not included in the film. Some farmers were disappointed that their scenes were not in the film. It was a mixed bag. But at the same time, they felt proud of the representation. And their complaints only reflected their disappointment for not being included in the film.

And what next? There is a body of work you have built over the years, when you conceive your next project in what ways do you think about your films in relation to your journey as a political feminist filmmaker, and the overlaps with the larger world of political and feminist filmmaking.

My work will always be from a political-feminist lens. Our art must be aligned with our nature or swabhav. We should spend time knowing who we are. I prefer not to make films at all, than make films that are not aligned with my nature or worldview. I veer towards those themes or stories which will allow more therao, introspection and possibility of exploring other layers beyond the socio-political, while at the same time being universal and not esoteric. Currently, I’m producing and creative-consulting on two very profound and urgent Indian documentaries. I’m also collaborating with a screen-play writer on an eco-fiction; and last, but not least, developing a non-fiction film. Non-fiction remains my first love, despite it being an unpopular and unglamorous form in India.