Nayab Noor Ikram (on the left) & Saadia Hussain (on the right), in front of the artwork by Ragnar Kjartansson, Scandinavian Pain (Neon), Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden, 2017

Saadia Hussain is a Stockholm-based artist, art educator, and art activist whose practice centers on collective art processes, often realized in public spaces.

Nayab Noor Ikram is a Finland-based visual artist working with moving image and photography, using performative and installation elements to explore the feeling of in-betweenship, cultural identity, and memory through rituals and symbolism.

NAYAB: I recognised myself when you mentioned having no role models growing up in Sweden. In Finland, the scene is smaller, making it even more challenging. For my generation of the late 80s and 90s, the boom in which racialised artists in the Nordics began to claim space happened around 2016-2017. It felt like everyone was starting to find each other. Before that, there was a great deal of searching, especially within institutions that lacked the tools. Had one been in the UK or the US, with resources and access to racialised academics and theorists on anti-racism, migration, and diaspora, it would have been easier. Many institutions we moved through were built for a predominantly white environment, not for the minority bodies. This also applies to the queer perspective, which has been more visible and progressive in the Nordics, making the search even more urgent.

Coming to Stockholm was special. Suddenly, there were many more people like me at different levels and contexts. And in the midst of it all, I was introduced to you, someone I share languages with – Swedish, Urdu, Punjabi – and the cultural attributes that come with that sharing. The generational gap made our meeting all the more valuable. You shared moments you had already lived, allowing me to reflect on myself and see the challenges you faced alone, making my path easier.

SAADIA: Raised in Sweden from age seven, going back to Lahore was a way to resist in my own way. Consciously and unconsciously, I felt: either this will consume me, or I need to find myself. I was searching for a non-ethnocentric field to move around in. I wanted to know which aesthetics excite me, and where I feel aligned. At that age, my thoughts were still nascent, a seed of resistance. I was young, a little anarchic, and the process itself felt provocative. I was questioned, not out of ill will but out of ignorance, even in my own surroundings. Sometimes, I fabricated stories to meet expectations, but that felt unhealthy. Trying to be an expert made me question: Who am I really?

When I returned to study fine arts at the National College of Arts in Lahore, I found not just a discipline but a sense of belonging. I wanted to feel ordinary, not constantly expected to be an expert on issues connected to my origin which I hadn’t yet explored. The program helped me understand the restlessness I was feeling and revealed how much of our cultural heritage—our stories, images, and histories—had gone undocumented or overshadowed. Confronting that absence deepened my connection to my roots and set me on the path toward anti-racist and postcolonial thinking… Pakistan and India carried the British legacy, echoing my family’s journey as political refugees. These lived conditions shaped the search for a new ‘home’.

Returning to Sweden, I cherished a belief in human rights, though that belief is now being questioned. That disillusionment drives me to invest my life here, through my artistic practice and raising children. I believe everyone has the right to be who they are, regardless of faith, origin, sexuality, or appearance. The Nordics, despite its challenges, remain a space for freedom and complexity – a struggle reflected in our art practice.

Saadia Hussain, Shared Layers, 2020, Lagersbergs IP, Eskilstuna

NAYAB: Oppression is not always visible in the Nordics. Many believe they have come far, but it becomes clear who truly faces the systematic stripping of identity. This is especially evident for non-white people. While others assume progress has been made, it is we who reveal that their successes are often an illusion.

SAADIA: Winds across Europe revolve around the idea of “the other.” Migration, austerity measures, and blame are placed upon “the other,” which in practice means our bodies. That is where solidarity begins. You and I have been given power and a mandate, and with that comes the responsibility to convey stories beyond our own, reflecting the experiences of many others. I feel a responsible towards bringing more people into these rooms. How do you feel about that?

NAYAB: My art always starts from myself and the feeling of being in-between. That feeling unites us, while the visual expression becomes the individual within the collective. At the same time, I regularly have opportunities to pass on to others – to diversify where I have power, in exhibitions, acquisitions, grants, or other contexts. I can challenge and present what might not always be visible.

SAADIA: We are not here to create conflict but to open up, mix, and allow justice to take place. In your artistic practice, your subjects invite people to reflect on their own experiences. There is a political tone in what we create, but it is also about being authentic in life. Sometimes our stories are diminished by being labelled ‘identity politics’. These are just our stories; the tone arises from the conflict between the context and the present. I find it interesting, though I can be allergic to attempts to diminish them by labelling them as diversity issues.

NAYAB: I often work with questions of cultural identity and similar themes. I also examine the language used to describe me, which sometimes reinforces the norms that have been set.

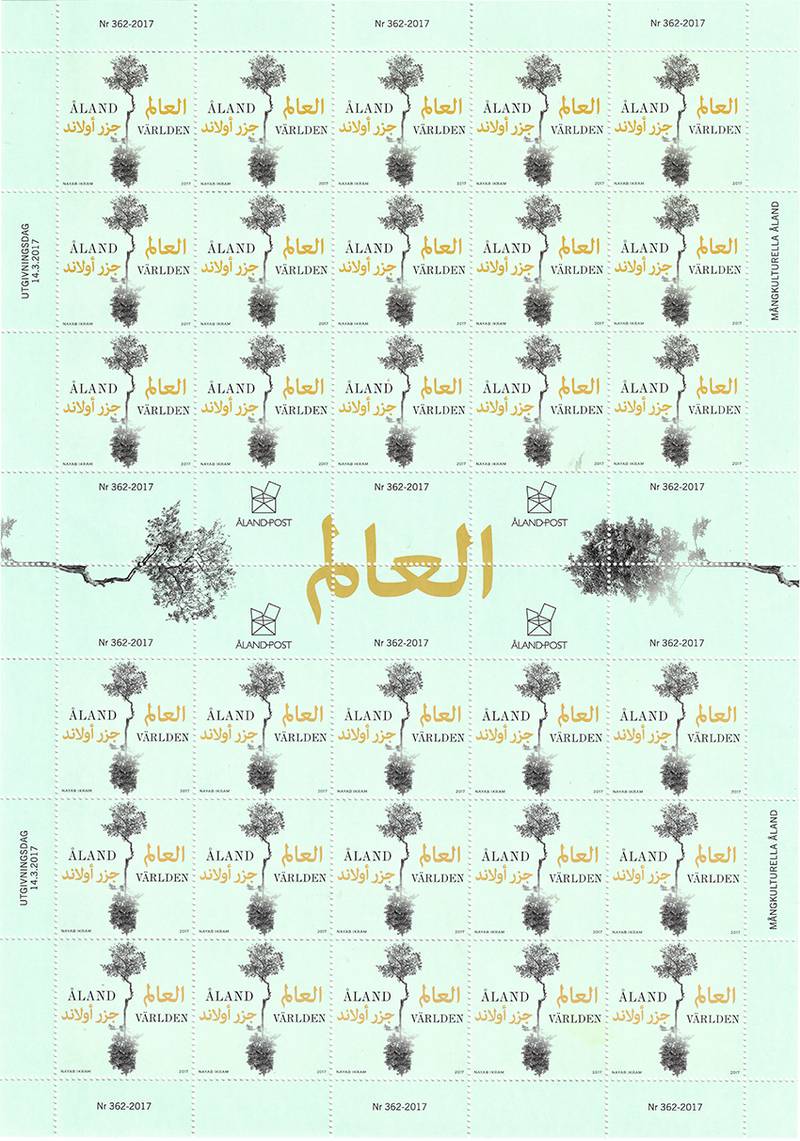

Nayab Noor Ikram, Multicultural Åland Postage Stamps, 2017

SAADIA: It is important to be vigilant about how we define ourselves and our artistic practices. We have the right to speak about our identity, even if it risks dismissal or being treated as a trend. My life and experiences are not a trend – they reflect a whole life, and the right to be complex and free.

Based on heritage, environment, and our response to the present, we create contemporary art. Life happens in this body, which has a certain appearance, yet we want to love, feel well, dream, and live fully. I have promised to embrace love and life, not let obstacles define me, to focus on freedom and dreams, to strive not to get angry, because injustice takes a toll both personally and socially.

We do not allow ourselves to be defined by others’ expectations. This is an opportunity to be authentic and honest, with the gaze and story coming from within. We do not cater to anyone else’s image of us. One must be vigilant, especially when opportunities are hijacked to fit someone else’s agenda. Creating art takes resources and time, and it is important to be celebrated for the right things. I often reflect on diversity and multiculturalism: is that what I am meant to represent? I engage with it, but always of my own free will – it is not imposed, simply part of the present. I also want clarity in my aesthetics: I carry my cultural heritage, but it is done here in Sweden – made, designed, taught, and produced here. At times I have held back so as to not be seen as exotic or “too multicultural,” yet it is precisely this aesthetics that excites me and is part of who I am.

Saadia Hussain, The Light We Reflect, Nobel Week Lights, 2025

These themes appear in my work for Nobel Weeklights, based on the Nobel Prize in Economics. Research shows that the Western world’s advantage is built on the exploitation of resources from elsewhere. Historical inequalities continue to create poverty globally, and their effects are visible in our societies today. In that sense, there is a logic to our being here.

This is what I have realised at 52. It has taken many turns to dare to be honest, embrace who I am, and see where that leads – not to dismiss it, but to find and meet others in it, so we can truly see each other. And even with the generational gap – how old are you, Nayab?

NAYAB: I’m 33.

SAADIA: We are almost twenty years apart, but it is precisely this – being starved of similar experiences – that binds us. What you and I share, I do not even share with artists I know in Pakistan. There is something about growing up in the Nordics and carrying this duality, this complexity, all the nuances we instinctively understand: our parents’ struggles, our families’ struggles. When I came to your family, I recognised so many codes from my own – how they searched for a home and in many ways found it. In Sweden, I haven’t met anyone else like you: a girl embracing art, the youngest in her family, with a Pakistani background. It has been a joy to follow your journey. We have completely different practices, yet I can still see myself in your work.

This is a sisterhood, a true artistic sisterhood. The years between us – I never wanted to see them as a barrier. Yes, we are from different generations, but that does not define us. What matters is how we think and what drives us. Wanting to become an artist ties us together.

NAYAB: I’m also grateful that my schooling wasn’t easy. It made it clear that the creative was what I needed to cultivate. In the beginning, that conviction had to be carried alone – how would I reach a point where my family understood that this matters, that what I do creates ripples? This became stronger when I had you. I could point to someone who felt like family within the field. And last summer, it became so clear that they understood that too; they felt at home with you as much as I do.

Because there was no Pakistani community on the Åland Islands, there was never a prominent place to see myself reflected. And when you combine that with art, where we question, challenge, and break patterns, you’re not only challenging yourself but also your family by choosing this path. You enter a field where the reaction is often, “What are we supposed to do with this?”

Art school was where I finally found my place, because everyone was different, and we were different together. I could breathe again. Once I embraced that difference, more subtleties appeared: the resources around me, who I could see myself in, and which experiences were missing. Finding one another in the BIPOC community, those who share the in-between, non-normative, racialized perspective, gives me the strength to go on. With you, I do not have to explain everything. I can just exist, and you understand the nuances.

SAADIA: Our parents – our mothers – truly loved us. That love gave us something essential: a confidence, a sense of self that rests on the feeling that I am valuable. That I matter, and I can do this. For me, it became clear early on that if I was already a little different, then I could also do other things. It was almost liberating – not having to try to be like everyone else. To be allowed to be different, and for that difference to become an asset.

Nayab Noor Ikram, Madri Zuban, Film Performance, 2024

NAYAB: Symbolism and language are something I see in both your expression and my own. I am attuned to the language of symbols, rooted in us through South Asian culture, from popular culture to art. Though educated in other contexts, we bring this language into our practice. It is layered, and depending on the environment, an object can take on entirely new interpretations. What excites me is using this symbolic language in a Nordic context, where it is not the most obvious form of expression.

SAADIA: After being educated in institutions, we find our visual language by digging into ourselves. As an artist, you want to tell, explore, or discuss the world. I love color, form, and symbols – they are visible yet hold something larger; symbols become keys to let others enter the work.

Making the complex understandable is the challenge. Symbols are like poetry: compressing knowledge in shapes and signs, inviting engagement and beginning a process. I value a class perspective on art, resisting inaccessibility. I want to embrace each person’s depth and inner world, enticing viewers through color, form, and attraction so they engage without overt explanation.

I do not follow narrow norms of what is “good” art. I explore language, intention, and approach, mindful of my mother’s perspective, aiming to communicate without arrogance or laziness. Subtlety generates understanding, and sharing that understanding is central. I consciously create authentic work while considering the audience, imagining doors wide enough for everyone to enter, not just those who fit a narrow mold. There is a broader desire for more people to encounter art.

NAYAB: You have to consider who your art is for and where it resonates. Who do I want it to speak to? Early on, in smaller galleries, you met visitors directly. But in institutional contexts, the connection felt distant; the work carried the dialogue while I stood outside, sometimes feeling lost.

The question became: how do I reconnect with the people I want to reach? How do I understand them? Dialogue is almost the art itself. The work may begin as a question, but it is through dialogue that we are challenged and try to understand each other.

SAADIA: Everything we do is a test; we move forward by asking questions, investigating, and making things visible. For artistic growth, we need to experience responses up close, because distant reactions are hard to grasp.

What has the context you grew up in and work in given you?

NAYAB: Being among so few had advantages and disadvantages. It made me more visible as an artist in Finland. I finished my education early, going straight from high school to four years at art school, and then into the field, with no gap years. I have been an artist for 10 years, and I am 33.

The biggest challenge has been language. There has been resistance to it, since Swedish is a minority language in mainland Finland, and I have been determined to be proudly Swedish-speaking, but it has bitten me many times, because I haven’t always had full access to the language. Sweden has been easier in that regard, where my personality comes through in interactions.

In Stockholm, I sometimes felt misunderstood, coming from the Åland Islands, a small town and small community, and Stockholm being the only metropolis in the Nordic countries. It becomes clear that I came from a place without access to BIPOC communities or a larger selection of art and culture. I have that access now, and I will always carry it with me.

SAADIA: I don’t feel comfortable in homogeneous places; it’s not as if I naturally belong in Pakistan just because everyone is brown. I feel most at ease when there is a mix of people – the diversity that grounds me. Stockholm has been like that my whole life.

Coming from an almost rural area to a big city brings its own cultural shift. It gives a different exposure. In Stockholm, there is diversity within diversity, with many dimensions to discover. It’s not like on the Åland Islands, where you might have to represent being a Pakistani artist. Here, there are more people in the diaspora, which gives more freedom.

We exist in this space of negotiating who we want to be. We get a buffet of possibilities – from the motherland, the home country, and the contemporary world. That’s what I embrace the most. I don’t have to take what I don’t stand behind from either side. I can create a fusion that suits me.

And I think of you because you live this doubly. You are part of the diaspora, but you also carry the added perspective of Swedish as a minority language. I didn’t think of that at first, but it introduces another sense of not fully belonging.

NAYAB: I feel strong in my Nordic identity, and it opens other doors. The structures in Finland are evolving, shaped by previous generations who did the hard work, fought the battles, and made it possible for others to have an easier path. Compared to Sweden, Finland is still developing, which gives us the chance to learn from its shortcomings and shape new discourses.

Visibility brings the responsibility to give back and share space, which is meaningful and demanding. As BIPOC artists, we carry multiple responsibilities, yet at its core, art is about freedom. I want to protect the time to explore and experiment, and to remember, a right I claim. I am not only an artist but also an artist-curator, facilitator, and participant in decision-making – culturally and politically engaged, often behind the scenes rather than at the barricades.

Saadia Hussain, Bokplats – en plats för mångas berättelser, Enköping, 2022

SAADIA: These roles are enablers, opportunities to act in the spaces we occupy. We take them with urgency because our time requires it, even if we don’t always choose it. Recognition brings responsibility and a desire to give back. Yet, I also want to preserve curiosity and experiment for its own sake – a reminder not to lose that while clearing the way for others. Many artists work this way: with care, tenderness toward oneself and gentle resistance.

NAYAB: For me, it has often felt like the artistic intention has had to be compromised. There were periods without the resources to create, during which energy went into other opportunities rather than my own work. Personal creation is about reflecting on what’s happening around you, and eventually, being seen brings opportunities to create.

SAADIA: Being an artist brings personal power. Wherever we are, we respond to injustices, guided by the reflection on right and wrong and not wavering from that – a political engagement we’ve inherited from home.

NAYAB: We have our parents’ principles, morals, and political values as our backbone. My father, already when I was a child, introduced me to the injustices in Palestine – growing up with parents who were aware of societal injustices shaped us. I think my father was in the same party as your father, the People’s Party in Pakistan, and that worldview informed us.

Nayab Noor Ikram, The Family, Film Performance, 2022

SAADIA: My father was a party secretary in Pakistan when martial law was imposed, and he spent five years in prison because of his political convictions. It was his imprisonment that forced us to flee and eventually come to Sweden as political refugees. Our journey is rooted in the desire to work for justice. I sometimes felt I was resisting a political path, doing something different from him – even in opposition – but ultimately I had the same passion and values. I began to see that everything is connected. I gradually embraced my teenage frustrations and reconciled with myself, asking: Who is really treating you badly?

What a privilege it has been to think differently and to come from a different family and home. Yet, when you reflect on how we ended up in these countries, with bodies of various colors and shapes, you realize how much that matters. Listening to you, your father’s story, and your mother’s inspires strength and courage.

Have you also felt that, because of their sacrifices, we must succeed?

NAYAB: We live the dreams they themselves could not dream. I also do not know all they dreamt of.

SAADIA: When I tell people I am an artist, I often hear an admiring “Ah!” Many have dreamed of that – it embodies freedom and creativity. In achieving it, we give something back to our parents, honoring them by turning that rare dream into reality.

NAYAB: Now we continue the fight.