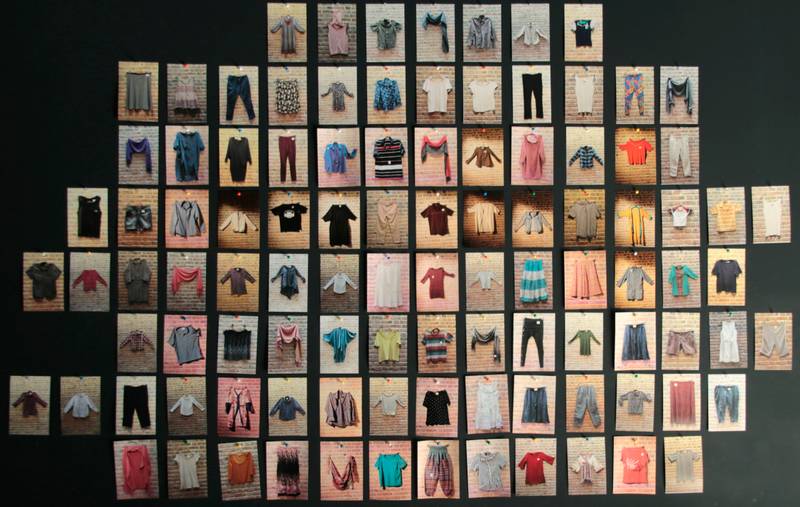

An Equivalence of Our Distance, installation view, 2021. Photo by Ahmadali Kadivar.

Golrokh Nafisi (b. 1981, Isfahan, Iran) is an illustrator, animator, writer, and contemporary artist based between Amsterdam and Tehran. Golrokh has studied at the Art University of Tehran in Iran and at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in the Netherlands. She has frequently exhibited her work in galleries, as interventions and performances, and at film festivals, among which Art Rotterdam in the Netherlands, MACRO in Italy, and the Beirut Art Center in Lebanon.

An Equivalence of Our Distance is a project of mine, done in collaboration with Ahmadali Kadivar, Ahmad Jafari, Maral Ashgevari, Parastou Sadeghi and Setareh Arashoo and Ehsan Abdifar. In this project, 100 letters were sent to the friends, relatives and acquaintances of the organizing team. In the letter, we described how we missed their hugs that had been withheld from us for a year due to COVID. We then asked them to send us a piece of their clothing that is old, worn out and whose life in their closet has come to an end.

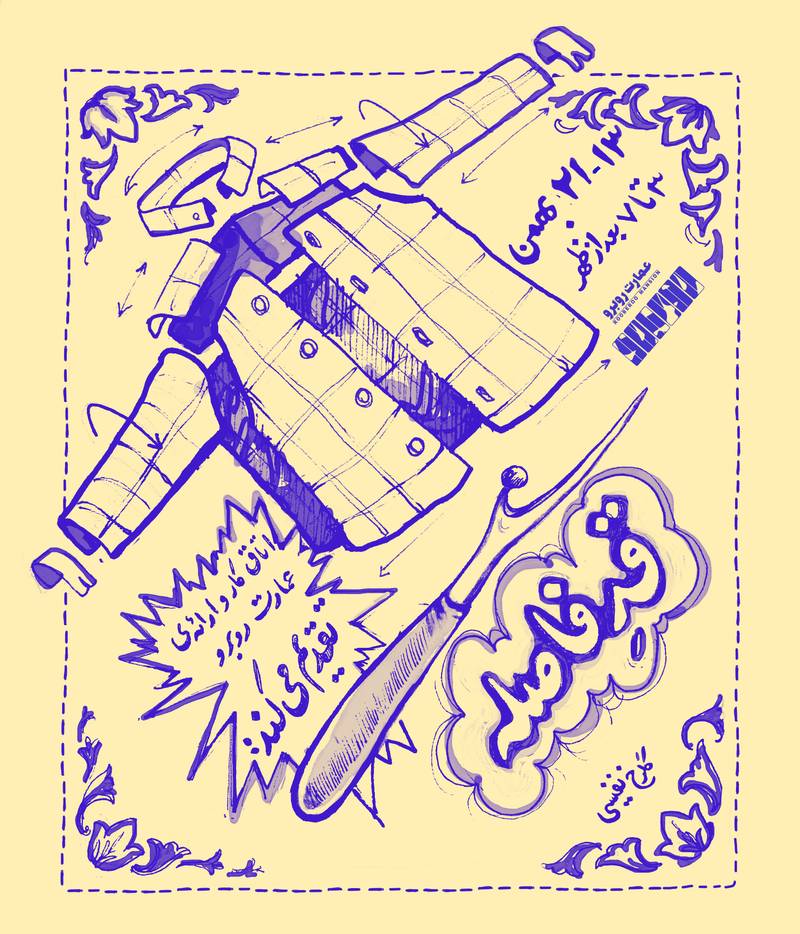

‘An Equivalence of Our Distance’ Poster, designed by Golrokh Nafisi, 2021.

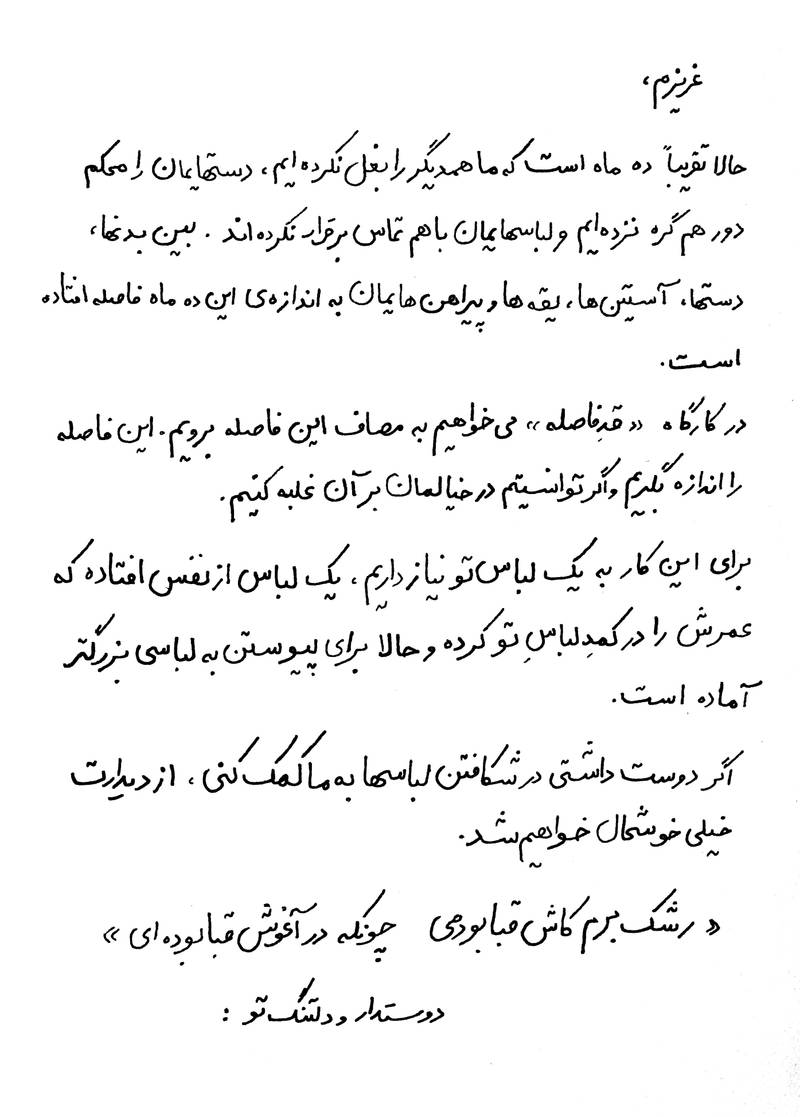

The letter sent to the friends, relatives and acquaintances of the organizing team.1

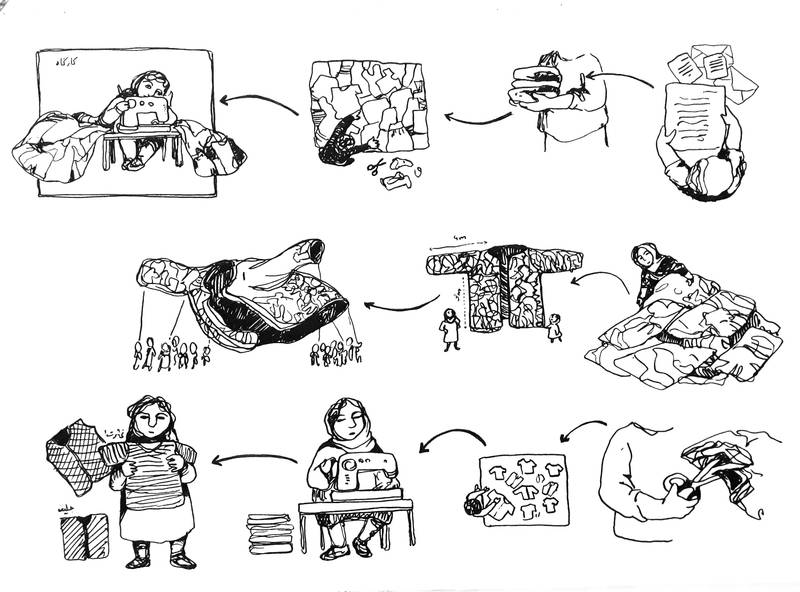

In response to our letter, which was sent by mail courier across the city, the recipients sent their old clothes to the location of the workspace, which took the temporary name “An Equivalence Of Our Distance”, and was set up in the back room of an experimental theatre, located down a small hidden alley in a mid-century mansion that was abandoned but has now become a performing arts center in the center of Tehran. The workspace consisted of three parts: registration of the clothes, dismantling/retiling the clothes, and re-stitching/sewing the fabrics together.

After being photographed and coded as part of registration, the clothes were passed through a hanging rail to the section where they were unstitched. Here, ten small seam rippers and chairs were installed for visitors to the workspace who would like to participate in the process of splitting. Participants, in masks, could sit in distance from one another and take the clothes apart, stitch by stitch, while seated next to each other, while talking or telling stories or even singing along. The workspace installation lasted seven to eight hours a day for three weeks. Participants spent many days returning to the workspace to split a particular pair of clothes that they had started to open. Garments that had been fully unstitched and had been broken down into the smallest of their constituent parts were sewn together in the connecting section. And at the end of three weeks of continuous work on splitting and re-connecting, the combined fabric reached ninety square meters.

At the end of the construction process, the large coat that had been created from all of the pieces of fabric reached the visitors through the location’s window, and from there it was hung atop a large hanger that had been built before.

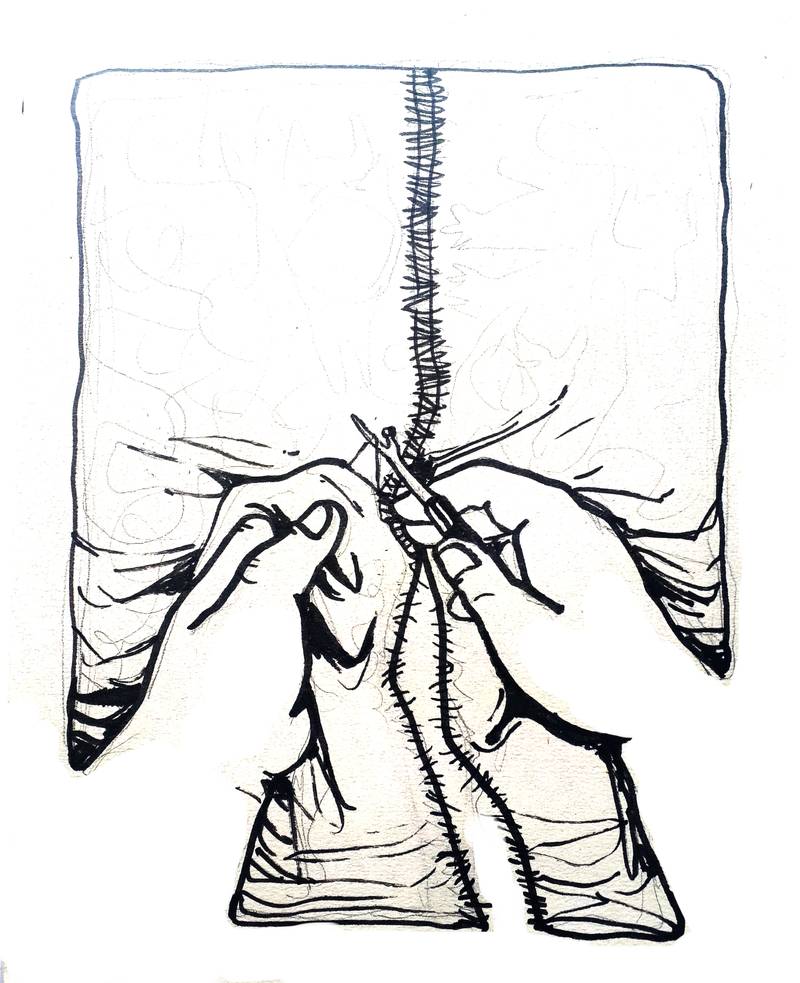

The workspace consisted of three parts: registration of the clothes, dismantling/retling/unstitching the clothes, and re-stitching/sewing the fabrics together. Illustration by Golrokh Nafisi, 2021.

What is present in our absence when we are not somewhere with somebody? There are objects that are present that materially fill up this apparently empty space in our absence. Let’s imagine ourselves as two points in space: what is in between us doesn’t always have the same geographical distance from our meeting point. If we consider distance as a qualitative measure of time and place in addition to the geographical size between two things, then for example the distance between a grandmother and her granddaughter is not equal to both sides. For a grandmother who sees her grandchildren once a week, this meeting is the most social event of the week. The way this meeting interrupts their usual flow differs for each of them. The grandmother perceives the time passed in distance from her grandchildren as a year, whereas the granddaughter sees it as a short break. To have an equal perceived understanding of distance, where should we begin from?

What are the objects that can represent absence? What items were touched by our friends, family, and relatives while we were away from each other? In terms of touch, surely their own clothes. When we meet someone without constriction, the first thing we touch is their clothing. When we are not there, their clothes hug them on our behalf. At first contact, there is a certain quality we feel in the fabric, its softness, its temperature, how it smells, the tears and discolorations, all tell us so much about who it belongs to. A piece of clothing, devoid of the body that has worn it for years, can represent an image of that person’s absence. This object traces distance in a way that resists the quantitative governance of a presence shaped by cyberspace and social media, spaces that regulate and control our interactions, giving us an illusion of experiencing something together.

رشک برم کاش قبا بودمی، چون که در آغوش قبا بودهای

“I wish I was your garment. Because you were curled up in its arms.”

— Jalāl ad-Dīn Mohammad Rūmī

In farsi, we use the word شکافتن (šk’p-tn’ /škāftan/) which means to unstitch, to cleave, cut, incise, to rupture, to split, but also to untangle, unwind, to open a topic. So, the people who were engaging with the process of unstitching were at the same time undertaking an active role in the social dynamic of the space. Strangers were sitting next to each other, wearing a mask, having conversations while having their hands busy. They immediately developed a vocabulary inherent to their actions, in order to exchange tips and tactics, while unwinding different topics and arguments related to their daily lives.

The clothing received, registered at the door by being photographed in its final appearance as a single complete piece and given an identification number. ‘An Equivalence of Our Distance’ workshop, 2021.

From our deepest desire to gather an imagined collectivity around us, we fantasize about going to each and every one of our friends, kin and relatives’ places to collect some garments they no longer use, as if they could be keepsakes of their presence. We sent out one hundred identical letters, with an invitation to send us one piece of their old clothes, no longer useful in their closet. If we united them all—we thought—we would be reunited again. So we set up a workshop space in the rehearsal room of a theatre, a space that was temporarily deprived of its usual function. Considering the scale of the collectivity, and the intention to include another kind of casual collective in the whole process, it was important to build the space accordingly.

Unstitching, illustration by Golrokh Nafisi, 2021.

The clothes we received had to be displayed so that the entire team could choose and get a sense of the variety of what was coming up.Beside our initial team of five, everyone who would come in to participate had to have both their own tools and a place to work, within a specific division of labour, which was carefully planned beforehand. Every piece of clothing we received had to be registered at the door by being photographed in its final appearance as a single complete piece and given an identification number. The participants could easily choose one by browsing the coat rack and joining the production line for unstitching. A seam ripper was given to each and every one of them to complete the task.

In farsi, we use the word شکافتن (šk’p-tn’ /škāftan/) which means to unstitch, to cleave, cut, incise, to rupture, to split, but also to untangle, unwind, to open a topic. So, the people who were engaging with the process of unstitching were at the same time undertaking an active role in the social dynamic of the space. Strangers were sitting next to each other, wearing a mask, having conversations while having their hands busy. They immediately developed a vocabulary inherent to their actions, in order to exchange tips and tactics, while unwinding different topics and arguments related to their daily lives.

Many of us might have in our mind the image of women knitting next to each other and talking. It almost comes automatically. In this situation, paradoxically, everyone was there to unstitch, to unmake that specific something—to deconstruct one thing into pieces that would later serve another purpose. There was a general subversive feeling of dissecting someone’s body.

For someone who keeps their hands busy, time is perceived differently. The duration is not calculated by minutes or hours, but by accomplished tasks—by how long it takes to unstitch a sleeve, or a trousers’ pocket, and so on, and the collective experience makes it worth coming back the next day to achieve what was started the day before. In household labour—which ideally is not based on exploitation—there is a different time regime. Several tasks are run simultaneously, without necessarily having to be fulfilled over a certain period of time. We do our laundry while we cook or knit a scarf, as opposed to the traditional time contract, which is regulated by counting daily production in an office or factory, for example. This household regime makes us understand the duration of time, which is based on quality, rather than quantity. In our workshop, the experience of the one piece of cloth coincided with time duration, which was also informed by the relationships among people, who were all busy with the same task, with different degrees of difficulty due to the garment type.

Throughout this phase, Maral realized that in order to connect two things—whatever they were—first, she needed to untangle everything properly. For Parastoo, splitting meant understanding—in order to understand anything, it is necessary to dedicate time to taking it apart. Ahmad felt like unstitching was a tunnel that would lead to the post-virus world, and we had to go through it together. Azin imagined a relationship between two people. By splitting up, we don’t lose a millimeter of either of them; they simply separate from each other.

The participants unstitch the clothes in the ‘An Equivalence of Our Distance’ workshop, 2021.

While the thing was being unmade, the idea of it belonging to a body was slowly abandoned in favor of a reflection on its production. There were distinctions between mass-produced clothing and tailor-made clothing. The mass-produced ones gave the feeling of coming from far away places that suddenly pushed us to check where they were produced—mainly from the far South East. Also, the fact that they had to be assembled quickly was made clear by their industrial machine-made overstitching. Throughout this phase, Maral realized that in order to connect two things—whatever they were—first, she needed to untangle everything properly. For Parastoo, splitting meant understanding—in order to understand anything, it is necessary to dedicate time to taking it apart. Ahmad felt like unstitching was a tunnel that would lead to the post-virus world, and we had to go through it together. Azin imagined a relationship between two people. By splitting up, we don’t lose a millimeter of either of them; they simply separate from each other.

Garments that were fully unstitched, broken down to the smallest of their constituent parts, had to be sewn together in one piece. ‘An Equivalence of Our Distance’ workshop, 2021.

Garments that were fully unstitched, broken down to the smallest of their constituent parts, had to be sewn together in one piece. ‘An Equivalence of Our Distance’ workshop, 2021.

At this point, garments that were fully unstitched, broken down to the smallest of their constituent parts, had to be sewn together in one piece. By the end of three weeks of continuous work on splitting and re-connecting, the assembled fabric reached ninety square meters. In the process of putting this together, there was an ambivalent feeling of both remembering those who these clothes belonged to and realizing—feeling their absence. Nonetheless, everyone becomes equal when distributed over the same large surface. When do we name a group of people a population (جمعیت)? When do we recognize a group of people together as a society beyond their individual numbers? The act of laying down these colorful pieces of fabric made of different materials, now devoid of any differences except for their color and material, was both a beautiful and painful process. beautiful in the experience of equality, and painful in the absence of society. This was especially true for those of us who had experienced participating in great social and political movements, those of us who were summed up in large squares in the heart of the city, with tight bodies living together and clinging to the waves of thinking. Living in the absence of this population, we never got used to it.

The fabrics were prepared to be merged into a single, large piece of garment. ‘An Equivalence of Our Distance’ workshop, 2021.

In the next step, these fabrics were prepared to be merged into a single, large piece of garment—a giant coat made of and by a collectivity. At this point, the whole arrangement of the workspace changed, and various music groups, including an Azeri-speaking female singer and a group of Afghan musicians and singers, were invited to perform alongside the sound of the sewing machine, in the middle of endless fabric rolls hanging from the ceiling. During this time, the remaining parts of the garments, such as buttons and labels, were combined into two large pieces to be used for the coat. Eventually, on the final day of a whole month of work, one after the other, all the fabrics made in the workshop from torn clothes were sewn together. On the last day, visitors could see portions of the coat from the window, while the sound of the sewing machine played from speakers in the courtyard of the theater, and sounds inside the workspace could be heard from outside. At the end of the assemblage, the large coat that had been created from all of the pieces of fabric was moved outside through the location’s window, and from there it was meant to be hung atop a large hanger that was previously built.

The large coat that had been created from all of the pieces of fabric was moved outside through the location’s window, and from there it was meant to be hung atop a large hanger that was previously built by the audience. ‘An Equivalence of Our Distance’ workshop, 2021.

The large coat that had been created from all of the pieces of fabric was moved outside through the location’s window, and from there it was meant to be hung atop a large hanger that was previously built by the audience. ‘An Equivalence of Our Distance’ workshop, 2021.

Now that a collectivity had been established, we asked ourselves whether we had the right to celebrate, in the face of more than a year of withholding. This deprivation also gave us a chance to reflect upon the very meaning of collective ceremonies and rites (آیین), in terms of where they come from and how they are enacted. Do we need faith to celebrate? Yes, indeed, but faith can also be a sensible faith—coming from something specific you perceive and make—collectively. We asked ourselves, who shall lead the celebration? Especially when the ceremony is meant to celebrate what we had achieved together. The leaders of people’s collective festivities are usually those who know about collective feelings—musicians. In large celebrations, folk musicians are there to lead people’s movements and emotions. They create patterns of sound to move people towards a factual or emotional goal. Music releases a force that nobody else can bring forward.

While the audience was carrying clothes and lifting it on the hanger, three folk musicians of Naqareh and Korna accompanied the ceremony. These musicians played pieces called Sahar Avazi (normally played in the early mornings after sunrise in the village, during a wedding party) and Jang Nameh, HeleJa (Nomad’s folk music from the Fars province of Iran). ‘An Equivalence of Our Distance’ workshop, 2021.

As the large coat was moved from the building to the outside and mounted on the hoop with the help of the audience, the load was pulled up by a rope that carried the hanger, in a collective effort. While the audience was carrying clothes and lifting it on the hanger, three folk musicians of Naqareh and Korna accompanied the ceremony. These musicians played pieces called Sahar Avazi (normally played in the early mornings after sunrise in the village, during a wedding party) and Jang Nameh, HeleJa (Nomad’s folk music from the Fars province of Iran). A statement was then read out loud. In this statement, first the city where the clothes were made was named according to the location of their factories—Vietnam, Bangladesh, Turkey, and so on—and then the neighborhoods of Tehran, and other cities from which the garments reached the “distance” workspace were named—Karimkhan, Iranshahr, Behjat Abad, etc. At the same time, initial photos of the workshop’s clothes, which were now placed in the body of the large dress, were distributed among the crowd, and each visitor took home a picture of a dress.

After all the time that was spent in the presence of absence, we had been wondering if and when we would return to a collective space. We spent nights figuring out possible ways of celebrating this return. A celebration is always a rite of passage. Can we revive these rites? Yes, as long as the audience is also part of the process.

This text has been written in conversation with Guilia Crispiani.

Golrokh Nafisi and the hung coat the day after the final show . ‘An Equivalence of Our Distance’ workshop, 2021.