The Backyard on the Seventh Floor. Corinna Helenelund 2020, HAM-gallery, Helsinki. Image Credit: Filippo Zambon.

Elina Nissinen (b.1991) is a visual artist based in Helsinki, Finland. She works with paint/ing and clay but also with other materials, space, and collaborators. Her curiosity in artmaking leans towards enigmatic matter(s) and objects, sensibilities, relationalities, narrativities, and magic. Elina holds an MA from the Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture (2018) and is currently pursuing her MFA in the University of the Arts Helsinki, Academy of Fine Arts.

I leave my bike on the side of the market square next to the pier where the ferry to Suomenlinna island goes. I look around, trying to spot Corinna; we have never met before. My first impressions of her base on our exchange of emails, a delicate mind-map she shared with me, and on what I know of her work. Corinna arrives with a light pushchair and a lively child in a baby carrier against her chest. They have come to Helsinki before heading to the archipelago, and we have decided to take a walk in Suomenlinna. It would be easier to talk while moving since the young, involuntary participant might get restless with no action around. Both of us have lived in Suomenlinna − Corinna in 2018, during her residency in HIAP. The weather is unstable, windy, and it begins to rain almost immediately we come ashore. I need to hold my phone before us to record the talk; broken screen downwards so the raindrops wouldn’t find the cracks in the glass.

Savu E. Korteniemi, Portrait of Corinna Helenelund, 2021

The resulting soundtrack is a picture with a rustling of sand, hum of rain, comments and complaints from the baby carrier, and meandering speech. Listening to it brings me back to our route that follows no prior plans and pauses once in a while so Corinna can care for the child’s comfort. I see us slowly moving through the landscape of brown sandy roads, cobblestones, hissing barnacle geese, greenness, the sea, and stone-made forts with caves opening into them like hungry mouths.

The island’s peculiar scenery fuses with our conversation, which is too drifting to cover here entirely. The following interview is an edited version of the talk we had this afternoon we got soaked in warm rain and took shelter in a tunnel that hundreds of years ago may have been a dungeon.

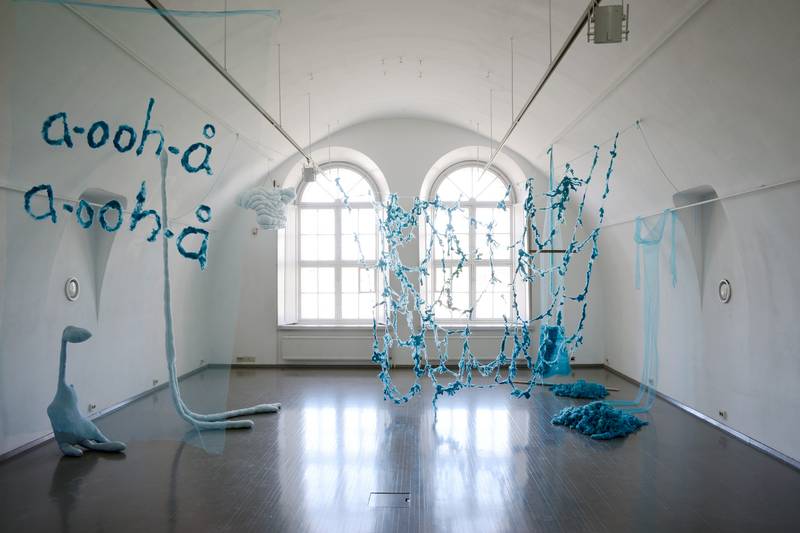

ELINA: You work with different types of textiles and with techniques like sewing, knitting, weaving, and dyeing. I remember your show The Backyard on the Seventh Floor at the HAM gallery last year. The installation combined abstract and spatial elements with semi-recognizable objects resembling insect-like beings, body parts, or clothes. Curiously, some of the pieces reminded me of Ikea’s FAMNIG cushions I cuddled as a child: pillows shaped like hearts or suns, proposing hugs with their open arms and long fingers. Everything in the gallery space was made of or coated with textile.

This usage of fabric, stretching it thin or wrapping things up with it, made me also think of skin as the breathing organ on the porous border between the bodily self and its surroundings. How does textile as a material intertwine with the thematic aspects of your work? Why are you drawn to soft textures and forms?

CORINNA: There are different reasons for my interest in textiles. Materials themselves carry inbuilt meanings, and we all have an intimate everyday relationship with textiles. We cover our bodies with clothes, and we rest on fabrics that coat the furniture in our homes. We also have this internalized sensual memory of the tactual sensations of different materials. Seeing one type of textile evokes the feel of its texture in your mind. The touch of fabrics is one thing, and their structure is another. A piece of fabric consists of yarns that, in turn, consist of loose strands that consist of twisted fibers. Fabricated of countless entwined threads, textile as material builds on openness.

As you also mentioned the skin — there’s this interesting concept called the Skin Ego developed by the French psychoanalyst Didier Anzieu. According to Anzieu, the Skin Ego encompasses several psychosomatic functions. It is a sack or an envelope that contains the Self. It is a sieve that works as a protective barrier for the psyche. Also, the skin is like a screen or display for the expression and (re)presentation of oneself.

Anyway, at first, using textile wasn’t a conscious choice but a practical solution in a situation where I didn’t have a studio space. I worked with used textiles and got a sewing machine that I could use at home. I had begun to work with this idea of embodied emotions, and I thought textile worked very well there as a material.

In a way, I see artmaking as using an extended language. It’s a way of thinking by other means than words. The works also communicate in their own way. Especially when brought together, they begin to interact and open into narratives.

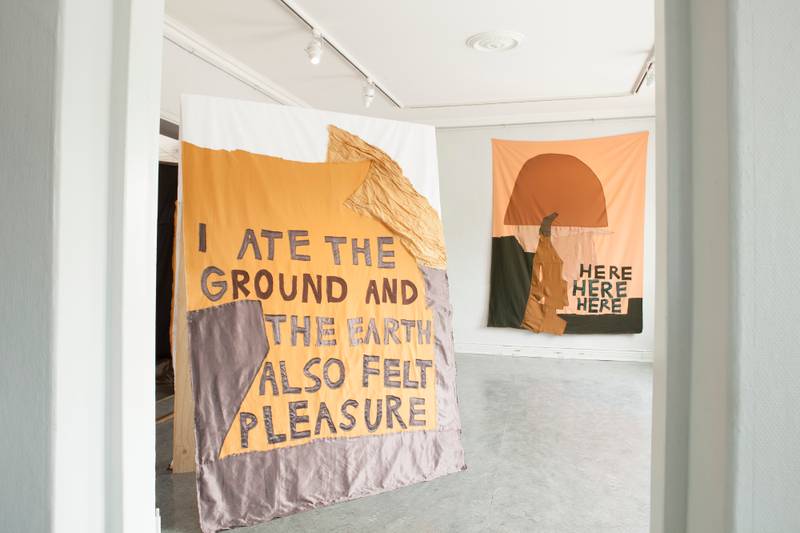

The Backyard on the Seventh Floor. Corinna Helenelund 2020, HAM-gallery, Helsinki. Image Credit: Filippo Zambon.

It seems you make use of your material in this way that brings forth its smoothness and evenness, but also porosity. Some pieces make me feel like you had zoomed in to show a fabric’s net-like structure on a magnified scale. What about the softness, then?

Yeah, I am very drawn to soft materials and this idea of soft sculpture. There’s something to these objects that stand but have no spine. They play with gravity and look different every time up. For me, this is not so much about flexibility but stubbornness: objects performing their own lives in their ability to adapt. There’s also this sense of closeness to soft objects. I like to think of an installation as a place to be in and be held by. To have a chance to rest and have a palpable contact with the work. I also totally get your association with the FAMNIG pillows, thinking of objects that invite you to touch them and get comforted by their softness. Be it a cushion or a bed, or a sculpture.

Yeah, and, as you mentioned, already visually sensing materials like textiles stimulate this imagined sensory feel of softness. Visiting an immersive, soft installation like yours, one enters a sensual space even if they didn’t lie down or otherwise touch the work. For me, there’s a fascinating clash between the softness, even cuteness, of your works and the strange and otherworldly atmospheres they create in space. Something is off-place or “in-between” like you have put it.

One factor to these impressions must be your specific use of colour. You often conduct an entire show in different shades of one colour. In 2017, you began to work on Pain Things, a series that misinterprets and externalizes emotional or sensual experiences into objects. All works from that series are in different shades of blue. In the Pro Artibus Foundation’s summer show Oasis, in Ekenäs, you have a series of works in green. You also collaborated there with Lauri Anttila on a piece that brings together some old understandings about light and colour in the form of a sundial and flowering colour wheel. How is your approach to or relationship with colours?

That’s a good question I don’t have such a clear answer to! My relationship with colours has to do with thinking of them as moods or as mind-spaces. I decide on them rather intuitively, entering into an abstract feeling and landing into a colour. The different work series are of different emotional atmospheres, and thus they are in different colours.

I see. In a way, your works are very colourful but then again, different colours are barely ever parallel in the same space or mixed: they always appear in monochromatic entireties.

Yes, I have intended to try and mix them up, but it just has not happened yet. E.g., the Pain Things series is in blue, as blue is found to impact one’s mental state in a calming manner and aid in focusing. For this series, I have worked with a visualization method used to treat pain and anxieties. You give a feeling or sensation a colour and then model it into a shape in your mind. You can then extract the pain, and I turn it into physical objects too. I noticed that giving the pain blue shades had a relieving effect. It was such a powerful experience that the whole series has come out in blue, as one landscape.

Colour and light are wholly entangled phenomena, and, like you bring up, it is interesting how notable psychological impact they have on one’s mental state and health. It is evident also with the lack of them, like here in these latitudes with such long darkness and short annual period of greenness.

That’s true. Since you mention greenness, for the recent green works in Ekenäs, I chose the colour based on the concept of viriditas coined by Hildegard of Bingen, a medieval mystic, philosopher, composer, and abbess. Viriditas often translates as “greening force," it refers to vitality and lushness and describes the colour green as the force of life. Viriditas exposed quite a brave holistic approach to life, thinking about Hildegard’s context in medieval theology. Medieval medicine recognized the importance of colours on wellbeing. Green was a popular colour in tapestries for revitalizing purposes through the sense of sight. One of Hildegard’s recipes I worked with scripts you to treat tired eyes by gazing at the greenness of grass until your eyes start to water. That should be a good one to try after too much staring at the screen.

With the red series then, I thought about an inside, particularly the warm inside of a body. There’s also a sense of restlessness and urgency to red. The red works were shown in the Night Again exhibition at Sinne gallery in 2016. I thought about night-sight and what happens to our ways of perceiving when the vision becomes obscured. One might physically see in greyscale in the darkness, but the feeling of the seen might still be red.

On the Subtle Influence of Nature. Corinna Helenelund 2021, Pro Artibus summer exhibition Oasis, Ekenäs. Image Credit: Ahmed Alalousi.

Night Again. Corinna Helenelund 2016, Sinne Gallery, Helsinki. Image courtesy the artist.

Night vision is a curious thing to think of; humans see so poorly in the dark. Colours wash off, but their ghosts remain. Observing things in darkness puts one in this weird liminal space where the perceived becomes a fair fusion of imagined, intuited, and sensed. Sensuality seems to be very at the core of your practice, but another thing I found noticeable in your work is the presence of text. Some pieces depict textile-made letters, words, and sentences. The palpable words seem to speak both as readable signs and image-like objects. As a word, the material of your works, textile, originates from the Latin word ‘text-’ which means ‘woven.’ To transmit something of the mental matter: emotions, thoughts, and visions, into embodied objects, is about a translation of sorts. Language, too, is always another representative version of what it describes. What kind of a role do language and textuality play in your pieces?

By textuality, do you also refer to the way objects speak? Or do you only mean text per se?

Well, this is an open question that you can interpret as you wish. Understanding textuality in a broad sense works very well!

In a way, I see artmaking as using an extended language. It’s a way of thinking by other means than words. The works also communicate in their own way. Especially when brought together, they begin to interact and open into narratives. I think that the series of Pain Things will eventually evolve into its own set of alphabets and form some sort of an obscure encyclopedia on the different forms of pain.

This is fascinating because (in a linguistic sense) languages are highly regulated and structured systems. There, communication aims at accuracy and homogeneity in definitions and interpretations. The kind of language you refer to then is inherently ambiguous and detached from literal meanings.

Yes, and that’s something I struggle with as I work with actual text. I use both my writings and borrowed quotes from texts I read parallel to the artmaking process. It’s hard to let the text feed into the work without it taking over. It easily happens that a text in an installation gets much louder, gets more weight than the rest of the works.

That makes sense. I mean, language anyway directs our perceiving and thinking. Everything gets named, categorized, and assessed by words and our use of them. Some of your works depict text that looks less like actual words and more like vocalized sounds, like moaning, right?

I think you refer to the work that was in HAM. That text saying: “a-ooh-å, a-ooh-å” is actually something picked from out here, from Suomenlinna. I was then in the HIAP residency, and, over a walk, I heard this odd sound. It was a very foggy and gray day, so I couldn’t see far and had no clue what it was. After a while, I spotted this bird, an eider duck. I checked how their calls transcribe: a-ooh-å is how it officially looks when spelled out in bird-watcher-Swedish. Brought to this particular new context, it became maybe more of a scream, but in reality, the bird sounds very funny and confused. They go like “a-uu, a-oOO??”

First there was ice, then fog, then light. Corinna Helenelund 2018, HIAP Open Studios. Image Credit: Sergio Urbina.

Ah hah, that does sound like someone surprised! But in the exhibition, in shivering letters and amongst the other blue objects, it became rather sad, like a cry or wail.

Yes, and I like that: how text as visual sound can carry and change its meaning. I also think about language as (a) space. You know, the way one moves within an installation and how language can function similarly to a three-dimensional space where one can navigate and build narratives. It’s hard to explain this… In her essay Writing blind: a conversation with the donkey, the philosopher, and poet Hélène Cixous brings forth the idea that the problem of books is in their form. They are forced into these rectangular blocks holding a pile of pages, while they in the process of appearing are more like spheres with windows opening to all directions so that one can enter the book from wherever.

Ursula Le Guin’s 1986 essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction shows similarities to this approach. In addition to its historical and social meanings, ‘the carrier bag’ applies allegorically to storytelling. There, the idea is that a narrative flows the best if it constructs by its own logic: you collect loose threads, thoughts, and things in a bag and let them mix and settle as they happen to fall at the bottom of the bag. I think that an installation works very well as a carrier bag and a sphere, too.

Yes, neither language opening from signs into notions nor tangible art objects opening into ideas are essentially chronological: readings and meanings are leaky and multidimensional. Things like the different ways the visitors’ bodies are and move in the space impact their encounters with and interpretations of an exhibition.

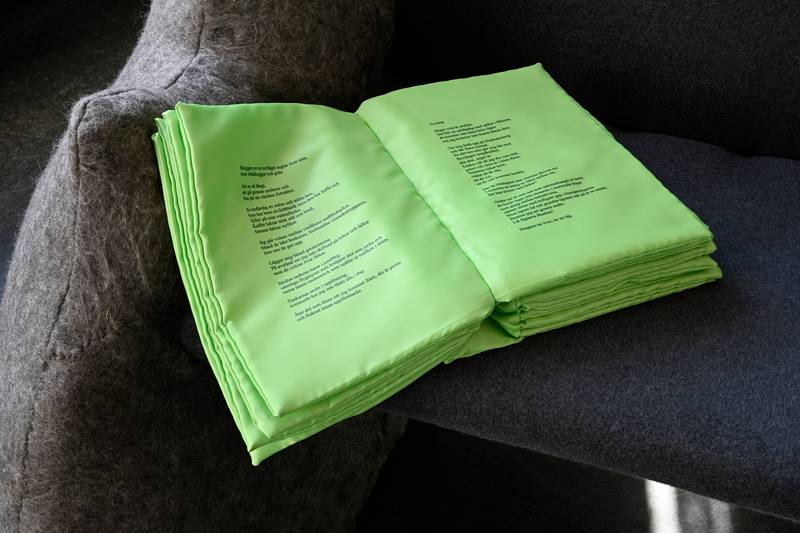

Definitely, that situation is kind of like reading with your whole body. Writing too can be a bodily process. When I started working with Hildegard’s writings, I made this one piece for The Light of the Dark Age, a duo-show with Lauri Anttila in Sculptor in 2019. Walking has long been a part of Lauri’s practice, and I thought we could collaborate over time by me starting to walk too. So, I walked the “Hildegard-Weg,” a pilgrimage route to Bingen, and wrote a pilgrimage diary. That text is, in a way, written by walking. I showed it in the shape of a soft book, like a pillow to read. The text was something very intimate and different from what I had shown before, and I was very nervous putting it in an exhibition then. But it did something that I could not do with any of the other works. There’s this dialogic and historical dimension to that piece, carried by the text.

Actually, my first text-works were made over a period when I felt pretty lost in artmaking: I needed to think together with someone. Through reading Hélène Cixous, I got into the Brazilian novelist Clarice Lispector whose texts made a particularly strong impression on me. I had never experienced something like that with reading before: it was both a deep recognition and a totally new space that her words put me in. I wanted to acquire some of her energy and thought, so I made a series of works based on her novel The Passion According to G.H. Making those works felt almost like putting on a costume. You know, wearing the language of another person.

The Light of the Dark Age. Lauri Anttila and Corinna Helenelund, Sculptor 2019. Image Credit: Filippo Zambon.

Fragment från en vandring. Corinna Helenelund 2019. Image Credit: Filippo Zambon.

I Ate the Ground and The Earth Also Felt Pleasure & Here, Here, Here. Corinna Helenelund 2014. Image Credit: Federico Ortegon.

It definitely makes sense to lean heavier on other thinkers and makers when feeling lost with your own making. Being lost is a topic I find pretty fascinating in itself, too. In her book Field Guide to Getting Lost, the writer and activist Rebecca Solnit writes about getting lost as a conscious act of choosing the unknown. Moving towards what escapes the known or comprehensible can also mean transfiguring oneself (or one self) as one has known it. Concepts like the unknowable and transcendental interest me a lot both within mundane and enigmatic experiences. As you have already brought up, you often draw references to the Middle Ages and medieval mystics. What is it about that era and those figures that feed to your work? How do their texts speak to you?

This is a good jump from textuality to medieval mystics because, in a way, Clarice Lispector is a mystic writer too. Her texts led me to approach writing as a place for mystic encounters, and through that, I got interested in this niche of women in medieval Christian mysticism. Language and writing play an important role in how medieval woman mystics delivered and described their views and visions. As a thinker who’s a woman, you were not allowed to study as widely as your man colleagues, so having direct contact with God could grant you the right to speak and write. At the same time, it was a difficult balance, and many visionaries got burned for being heretics. But, in one of the descriptions of where her knowledge comes from, Hildegard wrote that she didn’t receive her visions in dreams or through the bodily senses but with her inner eyes and ears. For me, this has something to do with artmaking, too. To allow yourself to have inner eyes and ears and to use them.

One must have had to prove herself on a whole next level to have a voice in the first place. I mean, certainly, the Middle Ages was no exception to the “Western cultures’” historical continuum of the rule of privileged white men. But yes, thinking of artmaking, I too find this idea of using your internal senses as something absolutely necessary. I guess it is like letting and anchoring yourself into this sensitive mindset or mind-space, turning your attention simultaneously “outward and inward.”

Yes. Another mystic that has entered my life more recently is Marguerite Porete. She lived 200 years after Hildegard and is one of the women burned on the stake for her writings. Marguerite wrote a book called The Mirror of Simple Souls, a dialogue between Reason, Love, and the Soul. At the beginning of the story, Marguerite urges the reader to put their reason aside. The text would make no sense read with rational logic. For me, this is a relevant note in the making and thinking of art as well. Sometimes the rational intellect is not the best guide in contemplating things.

Exactly. I think this attitude can expand from observing and contemplating also to knowing as something other than holding “truths” or having the answers.

Yeah, and maybe, as you said, this also has to do with allowing yourself to get lost. There’s something to this that I think the mystics can offer, not only for artmaking but for life in general. To take the unknown most seriously, and the search itself. Approaching the unapproachable with openness, presence, and attention. The soul was very present in medieval human anatomy. Hildegard perceived the soul as something spread all around the physical body, like the sap in a tree. This anatomy gives physical space to the flowing inner life, allowing us to be both fluid and flesh simultaneously.

Reading these texts is also a way to time travel. For me, these thinkers are geographically almost within walking distance, but their thoughts, which can be traveled through their texts, invite on new paths of thinking.

Of course, medieval texts are also difficult to read today in many ways. Hildegard, for instance, got a strict upper-class Catholic theological education. Despite her very empathic medicinal encyclopedia, she has also expressed many unsympathetic and intolerant thoughts typical of her time that are painful to read. I have used Hildegard’s own alphabet “litterae ignotae” in my recent green works. The obscurity of the letters exposes the great time leap from her days to ours.

Yeah, that is what sometimes makes it hard for me to get into old texts — and also into some new ones. You know, I get quickly bothered and frustrated by certain outdatedness. Anyhow. Your described sensitive tuning towards the “silent” things requires attention and an intensified sense of presence. My mind is always so all over the place that I find it difficult to feel fully present, even in my body. Focus is something many people struggle a lot with today, living surrounded by constant distractions and noise. On digital platforms, attention has also become an economic commodity.

Yes. The 20-century mystic Simone Weil describes attention as emptying one’s mind to be open to receive. She writes about how one of the most meaningful yet difficult things we can give to another person is our full attention; to fully receive someone else’s affliction.

Absolutely, it truly matters where we point our focus and attention. I’m thinking of your way of working: You recycle and recontextualize your works, putting them through loops of becoming something else. In the spring, you took part in the Uncertain Horizon exhibition at WAM in Turku. The show dealt with the sea, climatic upheavals, and, through the idea of the horizon, with ominous futures. Your installation combined pieces from different series shown earlier. What are your thoughts on artworks not having a fixed conceptual framework but a fluid one?

For me, the artmaking process itself is essentially fluid, and so is the place where the works come from. I try to allow my works some movement and openness also after being made. It makes them stay closer to their inherent behavior. I always work with series or families of works, and it often feels like different pieces grow parallel or tangled to one another. Sometimes the point or the essence falls somewhere in-between them. It’s like the meanings circulate the objects rather than belong to them.

Also, like words, artworks too speak very different things to different people. In new contexts, their meanings expand. Some of my works have been both on a stage and in gallery space. They behave very differently depending on the intensity and quality of interaction. I also have had works first in a solo exhibition and afterward in a group exhibition in someone else’s curated context. That was the case with the WAM show Uncertain Horizon. I talked with Terhi Tuomi, the curator, about how my works fit the given thematic frames. The subsection with my pieces was titled Deep Dives. Thinking again about how medicine historically observed the body as run by different fluids or humor whose balance was crucial, I think that especially the Pain Things resonated in that show. Those works have been fished from the fluid streams of emotions.

We then also discussed the enormous ecological problem around the textile industry. In a way, this now returns to the materiality of textile at the beginning of our talk. Some works that were in the WAM show I have made out of panne velvet. Panne velvet loses thousands of microfibers every time you wash it. What does that type of material do in such an exhibition context? Or the synthetic dyes used in some other pieces? It seemed paradoxical to discuss the ecocatastrophe with pieces made out of textile.

I guess it’s a bit early to know how pregnancy and parenting have impacted my practice, except in these super practical matters! But I found carrying a child a truly mind-blowing experience. And like with other overwhelming and hard-to-grasp experiences, it has been helpful to bring it into my work. There’s something so impressive to that situation: two people in one body. You have a stranger inside you. Or it’s someone you have never seen, yet, in a way, you know them because you get to know them from within.

The Backyard on the Seventh Floor, Between Breaths. Corinna Helenelund 2021. (On the right: Hydrotrope. Anna Niskanen, 2019). Uncertain Horizon, WAM, Turku. Image Credit: Ville Kaakinen / Turun museokeskus. Digital exhibition tour: https://digimuseo.fi/en/wam-turku-city-art-museum/

It’s interesting how a new context may underline the other, even problematic aspects of one’s work. But then again, you do use textiles anyway, and these materials are literally all around us in our everyday lives. There’s no point in denying that — and so, this can add a contradictory but at least very truthful aspect into such a framework, and vice versa.

That’s true. And the inherent problems of the material are anyhow present in the whole process. It is difficult yet fascinating to let go of control and allow your works to take on new contexts. Some of my used materials are natural fibers that will decompose while plastics remain longer. In this show, I imagined the installation from a future perspective. I saw this image of a strange underwater graveyard of objects refusing to decompose, made of materials that in that abstract future no longer exist.

Oh, that’s a curious and ethereal vision − thinking of the age of the oceans and the extraterrestrial origins of the Earth’s water. The matter that has enabled life here is actually alien to the planet. Metaphorically, water and the sea are commonly associated with emotions, intuition, and the subconscious. So, like you kind of said already, within the context of this show, I think your pieces were in place in discussing the emotional echo of the Anthropocene.

In the painted mind-map that you made to illuminate your practice for me, you have written “return to the water.” Those words grow in green out of the word ‘pregnancy.’ ‘Parenting’ branches to a list of red words, including ‘presence,’ ‘fear,’ ‘love,’ and ‘mental health.’ When I got in touch with you about this interview, you said you are currently learning to navigate professional life with a small child. I wonder what kind of an impact the experience of carrying a child and becoming a parent has had on your practice?

I guess it’s a bit early to know how pregnancy and parenting have impacted my practice, except in these super practical matters! But I found carrying a child a truly mind-blowing experience. And like with other overwhelming and hard-to-grasp experiences, it has been helpful to bring it into my work. There’s something so impressive to that situation: two people in one body. You have a stranger inside you. Or it’s someone you have never seen, yet, in a way, you know them because you get to know them from within. You are intertwined but still separate entities.

Studio view: work in the making. Corinna Helenelund 2020. Image courtesy the artist.

It has become even clearer how thoroughly working life and personal life can overlap and intertwine. There have been so many new emotions to go through. With childbirth, I thought I’d need to take back everything I knew about pain. Surprisingly, the pain relief method that I used in the Pain Things series, helped me a lot with those pains, too. Of course, this is something very personal because everyone experiences pain in different ways.

Another viewpoint to this is to think of pregnancy and childbirth as this existential place and situation. The early 20-century Hungarian psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi had this theory that we constantly long to return to the water. Life has to treat the trauma of leaving the water for moving onto land in the primeval times. Some animals evolved into mammals whose wombs are places for life to relive that trauma through every new individual starting life in water and entering dry land at birth. I can feel at home in that longing to water, and the thought of hosting a primal therapy session for Life felt thrilling.

I have earlier struggled quite a bit with accepting to have a physical body. Pregnancy altered my body relationship, as both my body and mind suddenly began to function in totally new and unexpected ways. As a feminist, I found it stunning how little I knew about pregnancy and childbirth, even if it is a threshold experience in many people’s lives. The first depiction I ever read on childbirth was the radically honest and inspiring The Argonauts by the American writer Maggie Nelson. Now that I have begun to work with this, I have read and listened to probably hundreds of different stories on childbirth. I wish it’d be similarly possible to reflect and write on the experience of death.

I have noticed that some dilemmas and interests reoccur and must be dealt with again and again over the years. The series I am currently working on brings together research on pregnancy, childbirth, and mothering with the slow process of learning to weave. I am picking apart and re-fabricating some works that were previously in the Night Again exhibition. For instance, my thoughts on the night as a place of altered reality have gained new layers due to sharing sleep cycles with first a not-yet-born, then a small child. Like we discussed earlier, old works will again continue their lives in a new phase of forms.

I find resonance in your described holistic and flexible approach to artmaking as a practice openly influenced by non-art-related lived experiences and changing contexts. Everything transfigures whether we want it or not: life never gets ready. The line between something being incomplete or “done” is very fragile, if even traceable. Besides, the completeness of things may not be their most relevant attribute in the first place.