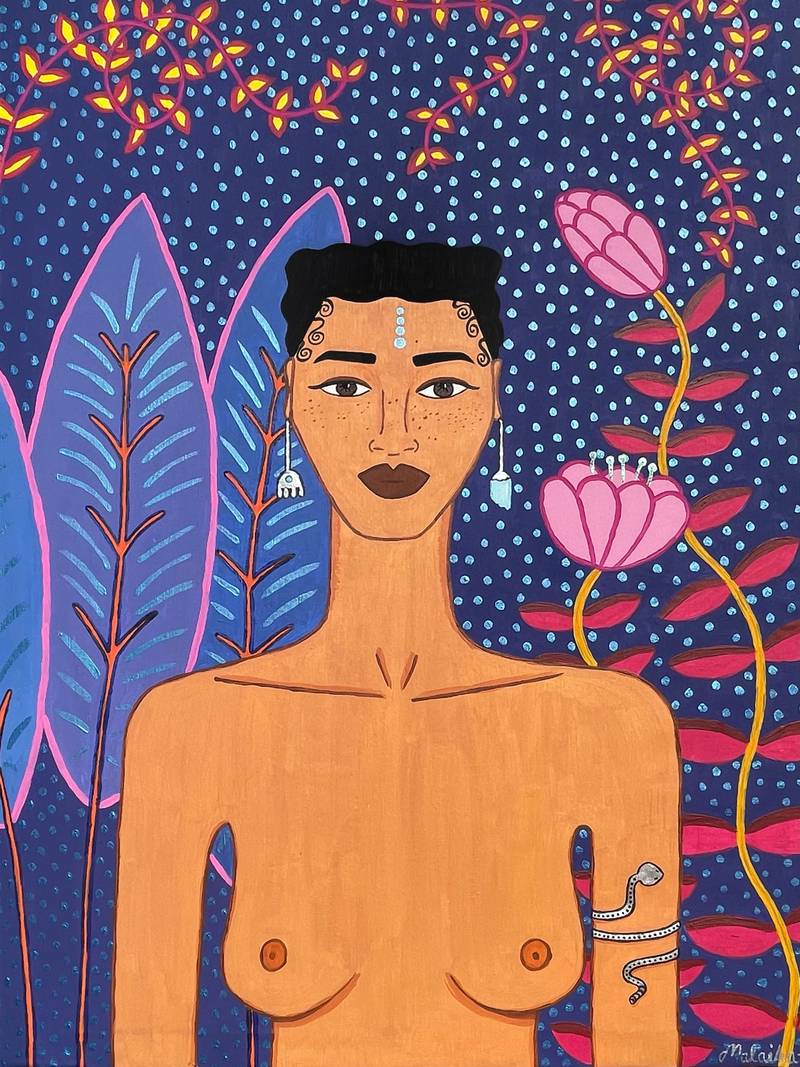

Mami Wata, watercolour, mixed media

Thomas Moose is a performer, a model, and a scientific researcher. During their performances, they explore the hotness and sexiness of their trans nonbinary body. They have a double Master of Science degree in International Nature Conservation from the University of Göttingen, Germany, and Lincoln University, New Zealand. Thomas is from Italy but is now based in Helsinki, Finland. They’re pursuing a PhD position and creating a life filled with science, different art forms and community.

A conversation with Kihwa-Endale on HANDS UP exhibition at Taidegalleria Albert in August 2021.

“When I started this series HANDS UP, I was living in my own world of hurt, and so my perceptions, my love and my art reflected this.

I focused on portraying Black men wearing clothing that was used to racially profile them.

I wanted to fight stereotypes with intensity.

The title HANDS UP was coined with police brutality in mind. But this quickly revealed how heavily I was leaning on the narrative of victimhood and internalized racism, amongst other isms.

Slowly I felt the need to express light and love with equal intensity.

The paintings you see today are what has come out of chaotic introspection, decolonization, emotional work and learning how to take care of plants.

The term HANDS UP has shifted its meaning with the paintings.

We do not only lift our hands in surrender and defence,

but also to praise, to celebrate, to dance;

We use them to pull each other up

The Black Lives movement in 2020 was another pivotal catalyst. All the mirror paintings I had up to that point have all been erased by now. They were no longer relevant once I started to ask:

Who am I without my mirrors?”

Kihwa-Endale from HANDS UP catalogue

Portrait of Kihwa-Endale by Malaika Mollel

I still remember the first time I saw Kihwa-Endale artwork in her studio. She was painting on transparent surfaces and mirrors. The paintings were getting alive, reflecting the light, the space around it and showing you your own reflection. Kihwa-Endale explained that the artworks were meant to portray multiple realities coexisting and play with the viewer. The mirrors were a symbolic choice at first. She was still figuring out where it was leading her to. She told me that “there is a saying: the universe has already written the poem you are planning to write. That helped me to unlearn how I approach the process of creating”.

One unlearning experience was to erase a whole painting, to be comfortable with letting go and finding trust in absence. “Even if I had spent months on something, the time I spent on it is not a reason to preserve it. It doesn’t mean anything if it isn’t what is meant to be expressed. It feels like I am only the vessel for each work”. Kihwa-Endale told me about the incident of the broken painting. It was an image of a black man wearing a hoodie and how this clothing affects racial profiling. The painting broke accidentally during the Black Lives Matter protest in 2020. But maybe it was not entirely an accident. Maybe it broke for a reason. “I felt like I didn’t have the knowledge on it yet, and that was such a learning experience. I tried to view it as a process rather than making something ready to show the world. This was hard at times because of the question: is it relevant if there is no visibility of what I’m doing? A lot about being an artist can get lost in proving that you are an artist by showing concrete work. 90% of me being an artist is invisible”. You don’t see what is happening. Artists rarely show the process of how you get there. We are judged on our final products and nothing else. But the process is one of the most crucial aspects of art. It is the process that makes you who you are as an artist. But what is art even?

Kihwa-Endale says that “to me, my art has been a tool for healing. Sometimes it is just about creative expression, and healing is a by-product of that”. Healing was definitely a good word to describe her artwork and the environment created during the exhibition.

Kihwa-Endale says "when I paint, I often don’t understand what it means as a full body of work. But at the exhibition, I saw almost everything I have been working on for so many years. I had this feeling that my subconscious knows a lot more than my consciousness”.

The paintings on mirrors were inspired by Kihwa-Endale own research on African culture and spirituality. It was also a way to connect with her own roots. The exhibition wasn’t only a space where art was displayed. Kihwa-Endale wanted to create a shared space and reinforce a continuance between the paintings, the art space, and the audience. “I wanted to experiment with how to create an inviting atmosphere. When you go to a museum, there is a gap between the audience and the art. I wrote the catalogue the way I thought it should be, but the words came out stiff and formal. Then I changed the style to write it as a letter that I was directly addressing the viewer as a friend”.

Spoken word poetry originated from the political urgency of the Black Arts Movement (1965-1975). Spoken word is a form of radical performance poetry. This poetry was a tool to spread the news on the black revolution and social empowerment in public places. It was also a tool to bring poetry back to people. Poetry had been classified for academic people only. But we all experience poetry in different ways. “The spoken word was about connecting with the audience to make it interactive. It is an art form that is very alive because the audience and performer feed on each other. I included this type of movement with the exhibition space too. One way was by combining different art forms. When you stop separating groups and art forms, everything becomes so much bigger and expansive. In that one week, in that space, there was painting, poetry, self-published books, a drag show, performances, and so much more”. In the gallery, you could have found two self-published books Children of Immigrants by Tania Nathan and No Justice, No Peace by Nathi Sihlophe, and Diaspora Mixtapes, a magazine by Ima Iduozee. These publications were chosen because they were created with a similar balance between individualism and collectivism.

The exhibition opened with Kihwa-Endale performing her own spoken-word piece. Four people participate in a spoken word workshop during the exhibition. Each participant wrote a spoken word poem based on the theme ‘who am I without my mirrors’. The poetry written during the spoken workshop became part of the closing reception. During the closing reception, there was also nonbinary and trans artists drag shows and sexy performances. “There was something really special about it,” Kihwa-Endale says. And I couldn’t agree more.

In an art gallery exhibition, there are usually two realities: the painting and the audience. But at HANDS UP at Taidegalleria Albert, there were many more. The idea of continuance and multiple realities coexisting was part of the exhibition. Even during the spoken word workshop, everyone made their own pieces, but it was collective and harmonious. There was a balance between individuals and collective experiences. “Our individual voices are stronger when we combine them together,” she says. The spoken word workshop was intended to redefine what does an exhibition mean. Is it showing something, or is it sharing an experience with the people entering your space?

*“The workshop was a space full of unique narrative, perspective, and experiences. It was beautiful to see people who had never met before supporting and loving each other”. It is very important to state safe space guidelines during a public event, but Kihwa-Endale “noticed that I didn’t have to do that. I hadn’t stated safe space guidelines throughout the whole exhibition. But I felt like it wasn’t needed. It was so implied. And, of course, that is very risky. But I wanted to know if it is possible to just trust people entering your space. To make that space, it is a lot of setting nonverbal intentions. I believe a lot in nonverbal communication. When we are in a space together, our nervous system connects with other nervous systems. We need to experience this! We live in a society where trust has little space. We always should be a little bit on guard. And it was really important for us to experience these types of spaces. This non-trusting way of being is the norm, and it shouldn’t be like that”. *

When you trust people, you give them power, and you create a strong connection with them. I was part of the spoken word workshop. Before reading my poem, I stated, “I’m a trans person that changed their name, I will pronounce my old name, but I trust you all to hear it and forget it because it’s painful for me”. I felt this warmth in my heart because I knew deep in me that I trusted them. You could feel in the room this sense of connection, kindness, and respect. I was able to share a piece of myself with people sharing the same space. We create vulnerable spaces just by stating certain things or by sharing our emotions or thoughts. By sharing your own thoughts and story, you give space for other people to question certain things or approach the same topic in other ways.

Kihwa-Endale quoted Wanda Holopainen in her exhibition and workshop, by asking “who am I without my mirrors?”. It provoked deep conversations that go beyond our own individual experiences. We talked about our own reflections in the mirrors, in our minds and in other people eyes. She left me with this question “do we only exist in the experiences others have of us?”. It’s a question that makes you think of where your experience exists. It made me think about my own experience as an individual part of a community. Once you understand you are connected and interlinked, your experiences overlap with others, and we collectively exist.

As we collectively exist, the line between the artist and the audience blurs. The audience is part of the art and the art space. Is art something you look outside of yourself or a space you’re part of? If we are part of it regarding who created the art piece, how do we reshape our idea of art and where it belongs? Based on this HANDS UP exhibition, we can create spaces and use art as a tool to build community. We can share this space with other marginalized people and become visible together. Because, remember, our individual voices are stronger when we combine them together.

Installation view of three paintings: Aquatic Jewels, Peace, Valley of Callus