Dafna Maimon, Leaky Teeth

Dr. Timo S. Tuhkanen (they/them) is an Omani born artist-composer and academic working at the intersection between contemporary music, art, and research on the historical and cultural aspects of touch. Currently based in Helsinki Timo is the founder of experimental publishing house Pteron Press, the director of Myymälä2 gallery, Affiliated Researcher at the Department of Music, University of Turku, Artistic Researcher at Angewandte University of Applied Arts Vienna, and is currently the Principal Investigator and founder of Microtonal Music Studios.

A I S T I T – coming to our senses is a traveling exhibition with a satellite programme, a publication and three part podcast and it happened/will happen in various locations in Paris, London, Berlin, Helsinki, and Ghent. The exhibition is curated by Satu Herrala and Hans Rosenström. The artists involved in the project are Maryan Abdulkarim, Etel Adnan, Axel Antas, Simone Fattal, Terike Haapoja (and their collaborator Ville MJ Hyvönen), Christine Sun Kim, Kapwani Kiwanga, Dominique Knowles, Kid Kokko (and their collaborators Tari Doriksen, Meri Ekola, E. L. Karhu, Anna-Mari Karvonen, and H Ouramo), Sonya Lindfors, Minna Långström (and their collaborator Mira Calix), Dafna Maimon, Laurent Millet, Maija Mustonen and Anna Maria Häkkinen (and their collaborators Sofia Palillo, and Masi Tiita), Kalle Nio, Laure Prouvost, Monira Al Qadiri, Kati Roover, and Hans Rosenström.

In order to review the exhibition I visited the exhibition space at Kunsthalle Helsinki twice, I visited the performance of Kid Kokko at STOA, I participated in Hans Rosenström’s and Kalle Nio’s sound work, I read the catalogue and website texts as well as the texts provided at the exhibition, and I listened to the three part podcast on accessibility hosted by Maija Karhunen. There was also a publication by Maryam Abdulkarim and Sonya Lindfors in relation to their work for the project, but because it is not yet publicly available, it cannot be considered in this review.

Since the exhibition deals with the senses my plan for the review was to try and experience it primarily from a non-visual perspective and focus on how the exhibition brings in the audience and allows them to experience and feel their way through the works.

A review in three paths:

- Do institutional structures allow coming to our senses?

- Dialogue on sensorial actuality: Is it possible to break the binary between metaphysics and phenomenology?

- Exclusion, Accessibility, and Disappearance.

Doniminique Knowles, Tahlequah

- Do institutional structures allow coming to our senses?

I missed my tram and was almost sweaty after walking fast from the train station to the gallery. The card reader at the counter didn’t work on the first try and the exhibition materials had run out. I rushed up the stairs as fast as I dared, and as gracefully as I could at that speed and stepped into the bright white space to the left of the staircase, saw someone I knew on the staff and asked again about the exhibition materials. I was kindly provided with the press release, the only paper document left describing the exhibition. The performance had already started – I wondered then for a second, slightly confused – there was something about the movements that I noticed but couldn’t place. I had rushed from home to make it to the start of the performance. I decided to just try to calm down and go forwards.

I closed my eyes to feel the performance. Sensing the smell of the mask I was wearing, the slight shifting and quiet rustle of the audience, the echo of the video installation in the large hall in which I was standing, but I couldn’t even hear the performance, let alone smell its designed scent. Upon entering, I had already seen Kapwami Kiwanga’s sculpture series Safe Space 1-3, placed at the entrance of the hall and reflecting the passage through and into the gallery space, the works miniaturised cavern and halls into which I could easily imagine entering, and which brought the question to my mind of ‘safe from what?’ the weather? other people? my own thoughts? They looked like they would tip over easily if I moved sightless. I had also noticed that nothing in the space provided me with a grounding of sense beyond the visible. My immediate reaction was to think about how strange it was that this exhibition about the senses and coming to our senses would immediately be so deprived of the senses with which to grasp basic movements, positions, or guidance without human assistance, without someone to hold my hand, or taking me around and yet that was something that wasn’t provided without explicitly asking.

I opened my eyes and focused on the breathing sounds coming from Laure Provoust’s Swallow. With its sharply measured sounds it seemed to contradict the free-flowing movements of the performance, which seemed to have un-followed time, staying in place not according to any fixed or choreographed gesture but only through the feeling within the poses taken, yet still showing to the sighted that a gesture was there Then it stopped and the performers got up and left the soft performance bed. Only now did I realise that I must have read the starting time of the performance wrong and arrived only for the last five minutes of it, only saved by my anxious rush to see how it begins and be present before the performance started.

I had an hour before I had to be somewhere else and I still had to buy the catalogue before I left. There were only QR codes on the walls and I didn’t know anything about the works yet. All I could smell was my mask. Only later I read in the exhibition materials that the performance had a designed scent, chosen together with Masi Tiita and which I had missed altogether in the space. I wonder what it was? How did it affect the performers? Did anyone in the audience notice it?

The room itself certainly seemed to be designed to embody care. Emanating from the bed on which the performance happened the space flowed softness, light, and the colour white, Axel Antas’s large photographic print series Lost for Sight was only the barest outline of birds which had landed on hands, figured as if in the air and hovering like a single hair had flown of someone’s head and just barely been glimpsed, just at the right angle to the sun, before vanishing into the haze and background. I thought it was perhaps a metaphor for mass extinction. To disappear into the beautifully constructed and framed background of human attention. The beauty was making the disappearance sentimental, I thought, it should have been making us angry.

At this moment, here, in this palest of dispersed light, I unexpectedly heard my childhood. The voice spoke from the next room and I immediately understood Monira Al Qadiri’s Divine Memory without seeing it. I doubted, knowing where I was, but hadn’t I had heard this voice, this tone, this measured pace of recitation of the divine abundance and grace of Allah’s creation a million times already? Hadn’t this sweet nectar of shared wonder passed through me also to make me love the phenomenal world around me, even if I disagreed with the cause of its creation? Yes, I knew and understood how my memory had passed through the deep seas and into observing something other than me, but which it, and me, could both understand. As I turned inside the middle room I saw that it was colourful but also midrange, I immediately thought of purgatory.

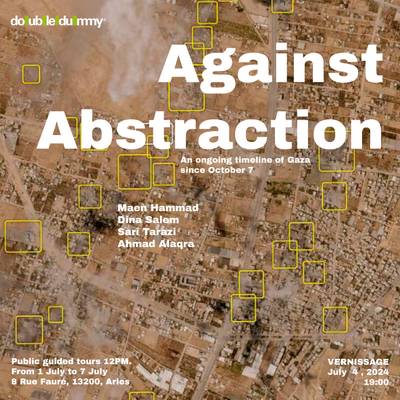

The shifting colours of the space shifted the space away from the bright white colour of the entrance, and brought me to uncertainty. Here, there were only questions and judgments. The lights breathed slowly, the projectors projected first on one wall and then its opposite, presenting a physical choreography highlighting the multiple points of view and perceptual differences of human experience and observation, with it, the audience also moved and through design they either turned around their chairs or moved them from one side of the room to the other in an attempt to see better and more clearly the opinions of the artists. Presented as argument of a thesis, the extremely literal works of Kati Roover, Salt in My Eyes, and Dominique Knowles, Tahlequah (the name refers directly to a famous killer whale, and while the name does not have any relation to the first Cherokee cities called Tahlequah founded after the Trail of Tears in which an estimated 60 000 people were forcibly displaced by the Indian Removal Act, the sadness of the work can easily be seen connecting to it).

While Roover’s video talks about feeling empathy for animals, Knowles’ video, like Al Qadiri’s, explicitly tries to bring about a different understanding of nature in the viewer through its montage and usage of documentary and archival footage. While Al Qadiri’s video presents more of an observation and separation of human from non-human, shown to us by the fact of being able to film animals under water and presenting this footage in museums to be different from animals. Knowles tries to make us grasp that this difference is in fact a fluid scale, rather than a quantized difference, in which human animals are at one part of the spectrum and whales at another.

In this space, I was drawn to Dafna Maimon’s Once a Wiggly World (1-6) which seemed oddly cut, like a groove in the designed atmosphere. Scattered on the floor, it interrupted the otherwise sterile and vague space for projections and it pulled the audience into a decision: should I follow these objects, strange, intriguing, and haptic, to the left, into an interruption or crack past one curtain the colour of which wasn’t certain, nor possibly even discernable, or should I continue straight, down the main path into darkness. The grey middle room presented us with a choice and in its Dantesque way, it best represented the title of coming to our senses and made it alive. But the question, do we come to our senses when we encounter our physical sensations is important, what is it about that experience that calls on us so strongly that we do? Does anything? If so, what is it and why? If not, why?

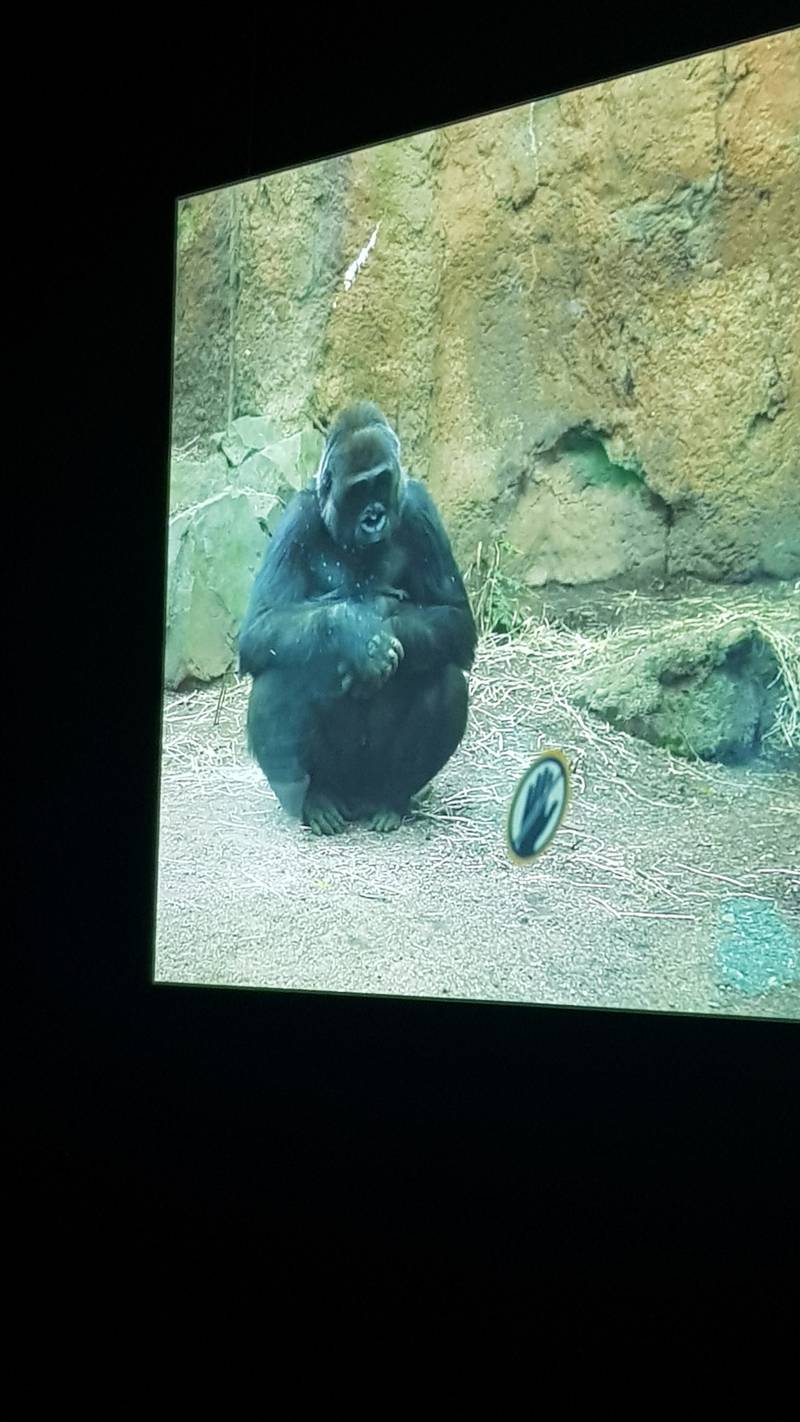

I read Terike Haapoja’s essay On Belonging after experiencing the work and I personally think the essay far outstretches the video work by its quality and depth. It is a superb essay on the problem of contributing. To me, it answers well the question of what does it mean to contribute today and how contribution can be energy from which the normative can learn to focus towards a more equitable social structure. The video part of On Belonging made me feel like a caged animal like the zoo watched me, and for a second felt like I was trapped in an aquarium. How does this relate to the essay beyond asking how animals contribute to society, and literally asking if zoos are necessary? The essay navigates the worlding of shared ideas and constructs, and the questioning of the idea of survival and current ways of commoning, community and its relationship to how our identity is formed and how we inform and mould that identity within a posthuman world that the video in its supposedly provocative stance as a finger pointer seems too literal and bland, and barely reaches the toes of the text.

The most provocative thing about this work was that it clashes heavily with Provoust’s work in the first room. The separation of the videos into dark and light rooms moreover increases this clash and when put next to each other like this that there is the dark or black animal in the zoo, captured and deprived, while the white human is in the jungle, in its place, it is hard not to think of discourses about colonialism and race, which otherwise were not present in the exhibition. Intentional or not, that darkness and our need to come to our senses about it are still here. Read Haapoja’s essay here.1

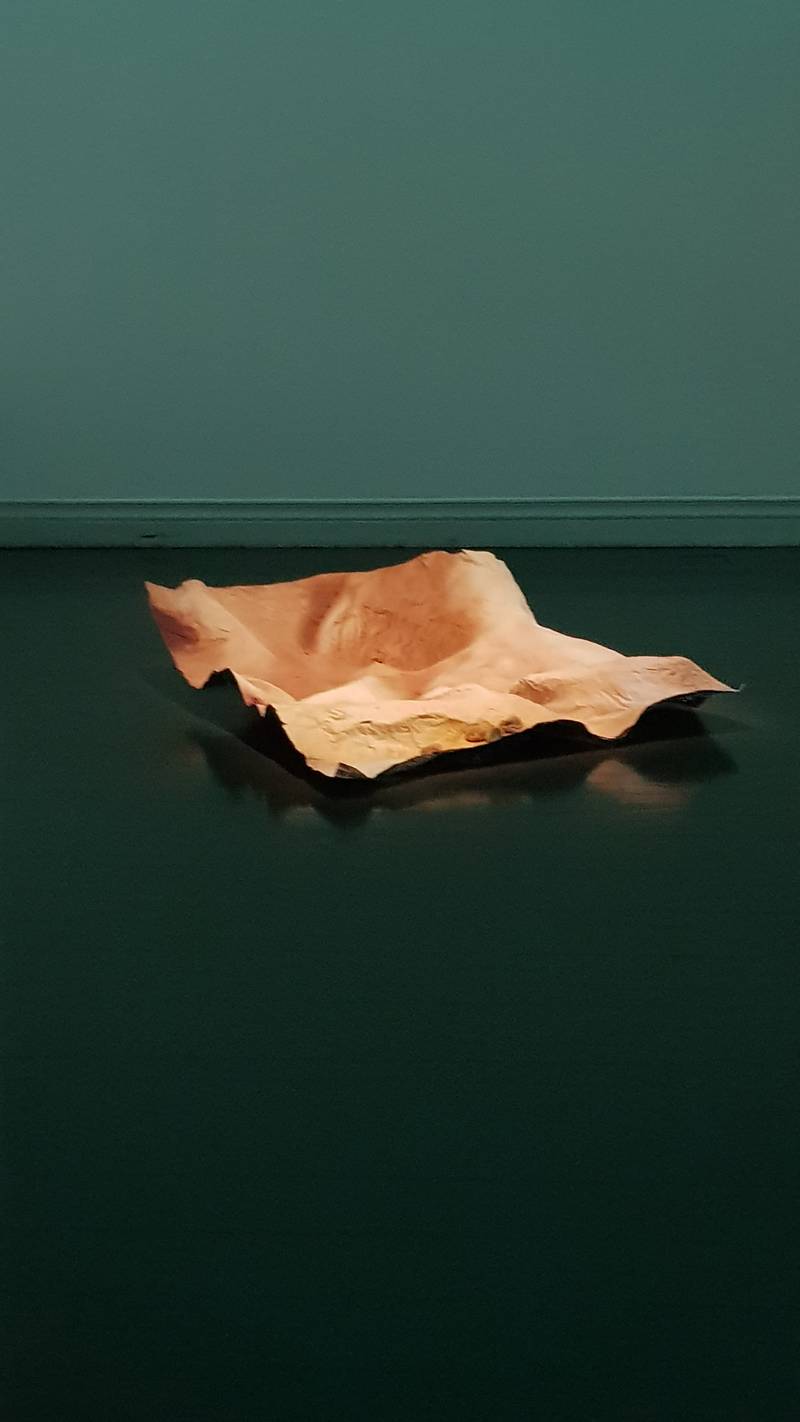

The dark room also starts to disrupt the magic of the exhibition, it is the least balanced, and the most problematic in terms of curatorial design. Two large projections in the same space divided by a curtain seems already like a solution to a problem that shouldn’t exist in the first place. The issue is only solved, really, by picking up the offered headphones and listening to Mira Calix’s composition for Minna Långström’s Photons of Mars without the distraction of the overly pathos ridden music in Haapoja’s video. Calix’s abstract composition was a step out of the otherwise literal presentations of the other works. As well as a video Långström presents us with a piece of mars, encased in a glass box which doesn’t allow us the tactile gratitude of verifying its realness (obviously we know it’s not real) but the conflict between the desire to touch the object and the resistance to our desire is fascinating.

I finally entered the crack, and in that space, I encountered a story about escape and regression. Now, there is the immediate issue of an inside joke in the video Once a Wiggly World (1-6) by Dafna Maimon in that it presents us what in Finnish is known as a hammaspeikko, a tooth goblin, but this isn’t recognized or acknowledged in the video or the exhibition materials and this makes it seem like a lost opportunity since the work is pretty funny. The video tells of an executive who has a leaky roof, and a leaky tooth, and how inside the tooth of the executive – which is depicted as a cave – lives some type of primitive humans who are connected to the outside world through their sense of touch and hearing. In the outside world, there is an eclipse about to happen, and here the eclipse seems to refer to some omen. For whatever reason, the executive and the primitive human switch places and the primitive human starts to experience the outside world (we never see the executive again) and after a while discovers the door and escapes to the outside.

This, to me, is quite a clear metaphor about the need to come into contact with our senses and that if we do we can be free of the idiotic constraints of a (capitalistic) society that bind us to being unaware, ignorant, and which want to stop us from coming to our senses about the world. There is an interesting conflict here – and I saw a glimpse of this repeating in Kid Kokko’s works as well – in the idea that (post-)human survival means that we need to give up our current humanity and regress to some earlier state of being in which we had not yet separated our lives from our senses and in which we could live touching, smelling, seeing, at the same intensity and which would inform our existence to an equal measure. There are severe problems in this interpretation of the senses, which I want to discuss separately.

The post-script in the corridor, another part of the work by Maimon, was absolutely fabulous. Made on velvet, the drawings depicting internal organs captured me entirely with their beauty. The physicality or the hapticity of the surfaces meant that I could both imagine their touch on me but also imagine myself drawn into them, of rolling in their feeling, or being the size of a fly and being encapsulated in their softness entirely and not merely on some part of my skin surrounded by the materials.

I entered the staircase for the second time, now on my way down and went to buy the catalogue. Once I read it, I realised that unlike stated by Chris Fite-Wassilak in the introduction, not every work of the project was present and missing was the work that I had, in fact, looked forward to the most. Christine Sun Kim’s work 4x4 was not in the exhibition and in fact, the curators explained in their discussion with Marja Karhunen for the podcast series about accessibility that it was impossible to have the work at Kunsthalle Helsinki.

Up until this point, I thought the exhibition was fairly good, the curators were both making their first large show and they were able to bring a difficult topic full of contradictions to the viewer in a coherent, if fairly one-sided view, partially due to the restrictions placed on them due to the covid pandemic. The curatorial choices up until this point were good, the artists interesting, illustrating points about the senses, accessibility, and posthumanistic relations. But the exclusion of Christine Sun Kim’s work 4x4 changed my mind. It completely flipped the way I saw the project, and this happened because the exclusion of Kim showed that there was a fundamental lack of understanding of the consequences of the theme and resistance to change within the structures in which the decisions were made. Why was it necessary to squash these possibilities available to the curators rather than make them blossom? In other words, it revealed that, very unfortunately, the project never came to its senses.

Maija Mustonen and Anna Maria Häkkinen, TREAT

- Dialogue on sensorial actuality: Is it possible to break the binary between metaphysics and phenomenology?

From the moment I entered the exhibition space with its passage from a caring light to a dark intensity, and moreover, especially after reviewing its written materials, I felt that the title of the exhibition ‘coming to our senses’ was a clear message about the nature of the senses in general.

The exhibition presents primarily two related aspects of the sensorial. Works in the exhibition present ideas, methods, and ways in which it is possible to better observe the senses, ways in which it is possible to come closer to them and understand them better, but also to better take care of them. The exhibition also presents works that present aspects of human and animal behaviour that can be argued to make no sense, i.e. they are not completely understandable. Together these two form a proposition about the nature of the senses, which I think is so interesting that it needs to be dealt with entirely separately from the rest of the review. That, if we as humans come to our physical senses and understand them better, we would stop our insane behaviour of destroying the world around us and committing terrible crime after crime after crime.

The problem behind this argument is that it would require the senses themselves to hold meaning. Rather than that, the meaning of the world is constructed by culture. Because of the way the issue is formulated, as not just being the age-old conflict between metaphysical knowledge a priori and phenomenal knowledge that is observed, the exhibition stirs some very interesting questions about the way in which artists are dealing with the idea of what meaning itself is.

The problem of any metaphysical idea of sensorial knowledge or of the senses as a location of meaning is brilliantly illustrated by Charles Sanders Peirce in his diaries:

A court may issue injunctions and judgments against me and I do not care a snap of my finger for them. I may think them idle vapor. But when I feel the sheriff’s hand on my shoulder, I shall begin to have a sense of actuality. Actuality is something brute. There is no reason in it.2

Actuality here is meaningful and it is constructed through culture (the judiciary system), while the touch of the sheriff only becomes meaningful through knowing the cultural situation in which it exists. It is easy to imagine that the sheriff’s touch is calm, gentle even, empathetic of the actuality that is about to happen, yet the meaning of it could not only imply a severe prison sentence, but also death. Whatever the actuality is of that touch, the touch itself doesn’t communicate it through our other senses. In this regard, it can only be speculated how different the exhibition would have been had it been possible to produce Maija Mustonen and Anna Maria Häkkinen’s Treat as a participatory artwork in which the audience is physically touched by the artists.

This looks like quite an insurmountable hurdle in the way of the argument I think the exhibition presents in its title. Not only that, when we observe the other senses besides touch and their abilities in influencing materials beyond our bodies, we notice immediately that they are extremely limited. My eyes for example, if I came to my sense of sight better and looked and saw better how would I transfer this to the world around me? A gaze, for example, is not my seeing something, but the appearance of my look in someone else’s eyes, i.e. how I appear when I look. The other senses also have this same problem that they have no active component in them, there is no way for me to make someone else taste through my taste. Touch is therefore the only sense in which this double component is available, and in fact, it is through touch that the other senses manifest into the cultural and socio-political world.

What does make the argument plausible is that the senses do hold various pleasures within them. It is pleasurable for me to look, taste, hear, touch, etc, and it is within this self-sensory framework in which it becomes interesting to engage in the thought process that would reveal something new about the way in which I, personally and singularly, can transform myself by coming closer and understanding better my senses. It makes me think what if there is a third option between or around the problem of metaphysical and phenomenal knowledge. Even if there is no answer yet, the fact that we can speculate around this binary, which remains perhaps the most important philosophical problem up until today, is important.

The question I am putting forwards is this. I will write this in dialogue form in order to tease out some problems and meanings and see where different lines of thought can lead:

– How can society be formed if the senses are meaningful only to me as an individual and in no way directly transferrable out of my body?

+ Surely this is just hedonism and individualism?

– But what if, let’s say, it’s not?

+ Then you would be speculating on the nature of the meaning itself, that it would be somehow special meaning – i.e. not that it would mean something special, but that the nature of the meaning itself would be special – which itself would not allow individualism, but it would be transformative.

– Wouldn’t that be wonderful?

+ But there aren’t any different categories of meaning.

– No?

+ I don’t think so, as far as I know, there aren’t any qualitative differences in meaning itself. Meaning as content is understandable and possibly transformative, but how would it be itself different?

– Well, it would only have meaning to me, like a personal language.

+ How could you make it meaningful for others, how would you translate it so that everybody could understand it?

– The point is that there is no need for that.

+ This is sounding awfully Cristian to me. And also blatantly false and selfish.

– There is definitely a flair of mysticism here.

+ So, but the meaning would have a communicable path to it, there is a methodology in achieving it right? That of coming to our senses.

– Yes, by approaching our own senses and getting to know them and understand them it is possible to achieve the understanding of the meaning in the senses.

+ Isn’t that just saying that you understand that hot is hot and light is light and so forth? What meaning is there in the senses that is not in the material world we perceive through the senses?

– Isn’t that question answered by Heidegger in Being and Time?

+ Could be.

– What if there is a dual quality to meaning itself, one that is only understandable to me and one which is culturally constructed, and I mediate the duality of meaning?

+ Do you mean “I” as an identity, which is a cultural construct, or “I”, which is something that you think and believe you are, i.e. “I” as an eternal and individual soul?

– Perhaps we are getting somewhere with this.

+ Perhaps.

– What if coming to our senses implies a phenomenal understanding of the world that isn’t existential?

+ I don’t know what that means. There are no existential phenomena of the individuals’ internal world. There is only that which we can perceive by the senses: its appearance and materialisation in the world. There is no way to prove the existence of the soul, and you would need that.

– Wouldn’t I?

+ Of course, at the moment the phenomenal extends only to the electrical signals in the body, those which people like Elon Musk so eagerly want to dominate and trigger. In order for there to be a qualitative difference between the meaning of the senses to you as an individual and the meaning of the senses to the world, you would probably have to be disconnected from the world, and well, people who suffer from severe schizophrenia and hallucinations know what that’s like. Isn’t that just fetishising a disconnection from reality? How would society work in such a situation? It would imply that there needs to be someone or something that would take care of us.

– But what if reality was fluid like that?

+The problem is that it would be mediated for us by someone or something.

– Is that a problem.

+ For me, yes.

– Not for me.

+ But in general I like the idea of a fluid reality. Of course, actuality will be a problem.

– So, we can’t get out of this problem between metaphysical and phenomenal knowledge and meaning?

+ Doesn’t look like.

The issue this dialogue is trying to present is the fact that there is an unresolvable conflict between the way the senses enable us to know something, which the exhibition leaves for the audience to discover. The exhibition doesn’t provide any tools to do so and it feels like we are merely dropped off at the problem, rather than helped to discover its facets and evaluate their claims to truth. This intellectual and philosophical neglect gives the exhibition a certain sheen or glare through which it is only possible to see slowly, revealing an interesting and complex, yet binary problem.

Terike Haapoja, On Belonging

- Exclusion, Accessibility, and Disappearance.

The third part of this essay revolves around the ideas and notions of accessibility that emerge from the exhibition. The reasoning behind addressing this topic separately is in two factors, the first being the work done towards accessibility, which for the standards of large exhibitions is well above average, but also the exclusion of Christine Sun Kim’s work from the show itself, which puts to question that work, making it at best patchy. While I genuinely think the exhibition organisers should be applauded for bringing the topic of accessibility to the fore it is more important to discuss the problems in order to not repeat them in the future.

First, it needs to be mentioned that the work of Christine Sun Kim was included in the Berlin edition of the project and there it was possible to find a space that could hold this work. It was only excluded from the exhibition in Helsinki.

Christine Sun Kim is a sound artist who is also deaf, while deafness is not a disability – in fact, the whole premise of this text is the notion that there is no such thing as disability in essence, but only the construction and maintenance of disability – the lens of disability theory can shine a light on why the exclusion of her work situates the project within the ‘construction of disability’ through the cultural management of the ‘fantasy of the normal’ in which it is possible to clearly see the ‘acceptance of the norm as a controlling principle.3

Being deaf, Kim approaches sounds very differently to people who hear and this approach to sound as a material vibration that can be felt or a visual system that can be seen is vital in her deconstruction of normative listening cultures. Unlike Noi and Rosenström who in their Weaving, Yearning use the sense as a trigger ‘other-worldly feelings or Mustonen and Häkkinen who use the sense of touch to try to visually express tactility, Kim doesn’t express sound sonically, nor wrench us out of this existence to another. The work actually does the opposite, it brings us closer to understanding how and why the senses are and how and why our senses are tied to the normatively constructed material objects that humans surround themselves with. Sound, especially infrasound, is used because it goes beyond our hearing to become resonant energy that penetrates and impacts the material world in a way that is sensible to anyone and anything with the sense of touch.

This excluded work was the only opportunity in the whole exhibition project for us, hearing people, to experience a work that clearly and explicitly emerged from non-normative sensory experience. While important to note, it is more important to understand why that would be important and I want to try and explain it using linguistic terms as a form of metaphor rather than literally.

It is important to know that Kim’s work is situated within a completely different sensory reality, a reality that exists in its own rights. While being a minority in the world of the hearing and thus is oppressed by normative structures, deafness has constructed its own cultural surroundings and situations which are its own and which are unrelated to cultures that hear. Understanding languages as cultural formations it is possible to see that when experiencing a work by Kim, it is us who hear who are put in the position of having to translate from one cultural language formation to another. There is no way to understand that work directly as an experience because it isn’t formed within a culture of the hearing, and therefore the subtle symbolic and metaphoric ideas it presents are not directly available to anyone who hears because they don’t have the ‘intertextual, psychological, and narrative competence’ for interpreting the meaning of the artwork.4 In other words, instead of trying ‘to preserve the psychological sense of the text (and to render it understandable within the framework of the receiving cultures)’ the exhibition excludes the work.

I found it very problematic that this exclusion was swiftly mentioned only in passing in the podcasts and that the issues surrounding it were never discussed openly or thoroughly because of the importance the project put on the senses and accessibility. In general, a wider communication of the exclusion of the work and the reasons behind the exclusion would have allowed an open and in-depth discussion about the way in which artists themselves approach accessibility in the content of their works.

While it is easy to talk about the issues surrounding the structures of artistic presentations and their problems with accessibility, the problems of accessibility in art are not merely whether there is a person opening the door or if there is an elevator or the seats are the right size for everybody. As long as the artworks themselves are inaccessible to everyone there is little point in discussing the problem if it is not accepted that the artists and artworks will have to change in order to be accessible. I want to quote at length the only part of the project’s materials which explicitly deals with artistic content and accessibility. From the podcast starting at minute 19:03 and typed in a way that is not a perfect transliteration but only removing various repetitions and fillers in order to make the language more readable:

Maija: ‘How did it feel? Satu you were talking about how the curator needs to be this mediator between the artists and then also the publics so for example in the moment of making decisions about how do we make this work more accessible, were there, was it easy, were there some kind of moments when you felt like somebody has to compromise too much, or, yeah?

Hans: ‘Not in this exhibition. I think. I feel all the artists we have worked with have been very forthcoming. That we have been able to caption for example their videos or Axel Antas who actually permits that his sculptures can be touched, and there are also other works that can’t be touched, because they are too sensitive, but in general I think that with dialogue together with the artist I think we managed to, at least a little bit more, make them accessible. But I can also see that it, for some works, or some types of works, that it creates a real challenge of how to make them accessible.’

Maija: ‘Like, for example?’

Hans: ‘Well, even in a video piece that an artist has made. It can, that’s a. If we imagine a highly visual video piece and you would imagine that it has a soundtrack and there might be words or something, and, but it’s thought as a whole and if you then would add the captions on the image it creates a very different focus on looking at the image and experiencing. Because then the words that are written also start to crave attention in a different way than was maybe intended in the first place. And I guess these are questions that need to be discussed, thought about, and I guess that’s also why we sit here. So I see that I don’t like I think it’s very individual…each work needs to be thought of individually how this could be made accessible, that there isn’t a rule that everything needs to be described or something like this.

Satu: ‘Yeah I think it can be a really creative and interesting process also of how to negotiate that what is suitable for this artwork and where are like the kind of the boundaries of that artwork. And what other ways of doing it so. I remember I guess like, yeah, these questions are always there with like with any kind of interpretation of artwork or translation of artwork, or now during the pandemic like we have been like had to find like ways of transmitting the works online for example and thinking a lot about interpretation and translation, so I think like maybe as a like an arts community we are getting more like better at that but, I hope, or more creative, or also, I hope that this moment in time has also widened our awareness about accessibility because suddenly art or performance events are not accessible for anyone, like physically accessible, and how can we learn from this moment together.

Maija: Yeah, I guess the reason why we even think about accessibility like I mean for me it’s enough of a reason to just say that, yeah, like every person has a right to experience art as an audience, and then also to aspire to be a professional artist. But I guess we can also add to it other things like accessibility benefits everyone or many people, this is often said, or that it’s, yeah, that it enhances our creativity or it gives new artistic possibilities or it makes art more interesting or whatever. But I guess the kid of the basis for that, for the whole, why we also sit here, and why we think about this is that art is a right. And yeah, that the corona time has made it very difficult to access suddenly for so many people…5

Accessibility is not merely about organizing the space so that people are able to get in and out comfortably, that doesn’t mean that the person can experience the art. In other words, being able to come to the artwork and have it in front of you does not mean you experience it.

The conversation continues from here but remains at this very general level about the content of the artworks, mainly discussing the problems of trying to translate artworks between the senses rather than discussing ways in which the culture of art can change. What is immediately noticeable about the discussion is that the curators present ideas from a normative point of view in which “anyone” is the majority of the population. The point I am trying to get across with this is that accessibility is not merely about organizing the space so that people are able to get in and out comfortably, that doesn’t mean that the person can experience the art. In other words, being able to come to the artwork and have it in front of you does not mean you experience it.

The real question is how to systematically alter the means of artistic production and as a consequence therefore the experience of art so that the art itself is accessible?

Kid Kokko’s work is equally interesting in this regard to change. While the artist clearly is interested in accessibility as a structural problem and their work highlight this by their inclusion of text in the performance itself I would like to take a moment to talk about the content of the work itself under the lens of accessibility and normativity. What I found most interesting in Kid Kokko’s performance is the desire to disappear and make all borders and differentiation of language and the world disappear. This touched me because the work so clearly touches on the notion of passing, of being unrecognised, of not being noticed for being different, and of not fitting into normative moulds and constructs held up by society.

Where I personally (so far) disagree with my reading of the performance is that I am convinced that the disappearance of all differentiations in society will lead to stratification and crystallisation of power as it is now. That there is no differentiation, to me, means that there is no possibility for change, because there is nothing to change into, and nothing to change from, everything is already the same. Not only is this a problem in any desire to change society for the better, but as a methodology it can be used by power to stratify society in its favour, thus leading to a less just world. I think David T. Mitchell describes it well within the context of disability theory, by saying that:

‘To request inclusion is to underscore one’s desire for assimilation into a norm that supports the perception of disability as an alien or exceptional condition. A community’s marginality is implicitly underscored by the request for inclusion itself. If disability can be theorized as essential to our definition of what constitutes the human, then the integrable must take a back seat to the integral. Stiker’s historical analysis demonstrates that in each of the key epochs of Western thought-the classical era, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Victorian age, the modern-that disability and disabled populations continue to surface as that which must be assimilated or made to disappear. The less visible physical and cognitive difference becomes, the more a society can pride itself upon its own illusory value as a human(e) collectivity. The “success” of integration can be based upon a variety of assimilation strategies, from legislative policies to segregation to eradication, but Stiker argues that there is a disturbing ideology underwriting each action along this continuum-the social ideal of erasure.’6

Being different and experiencing a different world and culture and wanting to keep that difference is not a bad thing. As I read it, disappearance in this sense, in actuality, is not the disappearance of all evil but its victory over differences because the ‘erasure of differences [is] the ultimate goal’ of preordained social order.7 Only by being different and refusing to be integrated while retaining the right to contribute to all society is it possible to construct a society that benefits everybody.

My aim here is not to pit disability against queer or trans by discussing the issues surrounding the idea of disappearing and the location from where the desire to disappear arises from. Be it fear of being hurt or violated, of desiring to belong and be loved in the same way others seem to be, leading to an idea that fitting in and being unnoticed will garner that. Or in a total way of making everything disappear through hate and destroying all differences in the desire to make them go away for everybody in order to help form an equalitarian society.

The problem with disappearing in my mind is that fluidity requires difference, to transition requires difference, and transformation is the most important thing today. Not only is fluid a reference to solidity, but in order to create flux, heat, cold, sensations that we feel on our skin tells us of the differences and their transition of material flux. With these differences we know something, with them we are able to feel. Without differences, we are not able to feel each other, and without each other, the world really is meaningless and void of relations, since there is no higher being of purity into which we dissolve, no combined soul that gathers our parts after we fall. That’s why when I think about disappearing, it is just another pointless death.