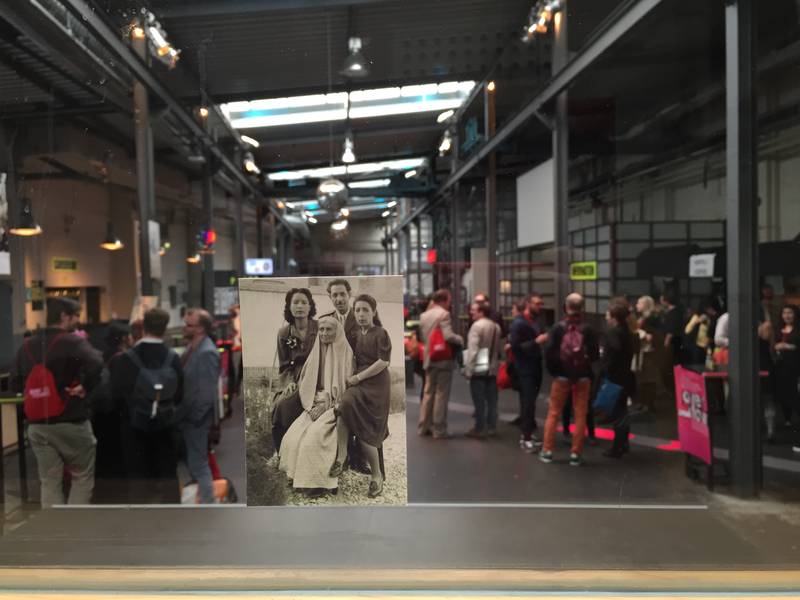

Tara Fatehi Irani, Mishandled Archive, London, 2021. Photo by Jemima Yong.

Nisha Ramayya grew up in Glasgow and now lives in London. Her poetry collection States of the Body Produced by Love (2019) is published by Ignota Books. Recent poems and essays can be found online in CCA Annex, JUF, and Spam Zine; and in print in Wasafiri and Magma. She teaches Creative Writing at Queen Mary University of London.

Mishandled Archive started in 2017 when Tara Fatehi Irani dispersed an archive of family photographs and documents in public places and created a dance at the site of each dispersal–once a day for a whole year. This led to the creation of a new archive of 365 photographs and dance scores, a performance-installation and a book. In summer 2021, Tara presented the first outdoor performance of Mishandled Archive. She invited poet Nisha Ramayya to attend this performance and write a response to it–to write around and through the performance and its themes, to create a text that thinks with this performance and allows its readers an alternative way into the project.

Nisha and Tara did not know each other until then. Tara said: ‘I’ve read some of your writing (which is brilliant) and I think your creative-critical approach would be a great match for the ethos of Mishandled Archive and the kinds of processes I am also interested in.’

Nisha said…

Missing her friends—her London family, as she described it to us one rosy winter evening—Špela travelled from Dolsko, the village near Ljubljana where she currently lives with her mother, to London. We met almost a decade ago as doctoral students (her project on migration and intergenerational knowledge after Yugoslavia; mine on Tantric ritual, community, and experimental feminist poetics). Neither of our relatives lived close by for long. I may be misremembering, but the first time we properly hung out was after some feminist march or protest (the Dyke March in 2013! – confirmed in the group chat, our ongoing archive). Rather than travel all the way back to Stoke Newington, I went to Špela’s flat on Old Street to change. She donned a cloche, a tie, and an unread novel by Djuna Barnes; I assembled a ‘tenth muse’-style drapery with dupattas, and we were ready for the Modernist Salon at Eley’s flat in Ealing! (These days, that sentence must be followed by numerous Loudly Crying Faces.) Memories from the party itself are scarce, except for a shadowy round of ‘pin the phallic object on Freud’ (all credit to Romaine Brooks, our dashing host).

What were we worried about at the time? Rising COVID-19 cases in Scotland paired with a devastating increase in drug deaths and suicides; the infrastructural violence towards people by governments eager to blame an ‘invisible enemy’ and distract from their murderous capitalism; and protests for trans rights in London that belie the notion of human rights in the UK when people must call for the recognition, protection, and care that the neoliberal state claims to provide.

And we last hugged outside Canonbury station in August, near the flat where Špela lived for 3 years, me for 6, Laika 6, and Kate 9. We’d just met our godchild, Ambrose, posing for family photos whilst his beautiful human and furry caregivers looked on, Eley, Nell, Lily, and Bryher. Taking the long walk back from theirs to visit our old home, we admired Diana’s houseplants from outside, missed her, and smelled the roses in a heavy-handed gesture of nostalgia, that old-friend blend of sorrow and love. Špela’s and my experiences and recollections of this moment are not identical. The collective pronoun feels fragile and hard won; my ‘we’ doesn’t presume to know how Špela’s ‘we’ would sound, or how she would describe our positioning in relation to each other and our implicated lives.

‘In memory of the deceased, please move five centimetres before you continue.’

A couple of days earlier, Špela and I attended one of four outdoor performances of Tara Fatehi Irani’s Mishandled Archive in Peckham Rye, 20 minutes down the hill from where I live now with Rob, Worf, and Ticklepenny (so close to Tara that she hand-delivered a copy of her sumptuous book several months earlier). I wore my midnight blue trousers, Špela her pink silk shirt (‘the gossamer blush silk blouse hand printed with native Australian plants’, she described, in her best bad novelist; it seems we never left Eley’s l’académie des femmes). I think it was around 25° C – Tara carries a thermometer to take the temperature of her performances and will know for sure. The sun was shining and the queue for ice cream was long. There is something unnatural about this scene, its brightness distorting against the global continuities of crisis that we live within, that sustain a few (and are sustained by those few), pierce some, and engulf most. What were we worried about at the time? Rising COVID-19 cases in Scotland paired with a devastating increase in drug deaths and suicides; the infrastructural violence towards people by governments eager to blame an ‘invisible enemy’ and distract from their murderous capitalism; and protests for trans rights in London that belie the notion of human rights in the UK when people must call for the recognition, protection, and care that the neoliberal state claims to provide. Špela and I also spoke about the US, India, Australia, and Japan, places where we have loved ones and deep connections, and places, people, and connections that we have lost. In writing about it here, the scene is filtered through grief and the memory of a friend whose burial I attended in the days following the performance.

Tara Fatehi Irani, Mishandled Archive, London, 2021. Photo by Jemima Yong.

Tara Fatehi Irani, Mishandled Archive, London, 2021. Photo by Jemima Yong.

Tara and her team created an installation amidst the trees of the Japanese Garden; notecards were hung from branches and ribbons were tied between trees, shimmering in the breeze, conjuring wishes, spiderwebs after rain, and flung trainers. On every tree, a bottle of hand sanitizer spun on a white ribbon of its own; a curious herald, inviting us to touch and forewarning us of touch’s dangers. Not having gone to an art gallery in ages, thus not having had that art-induced gusto for unlawful touch, we accepted the invitation. The notecards featured cut-outs of b&w family photographs posed in public spaces in London, Tehran, and many other sites and snapped by Tara on her phone – they can be seen on Tara’s Instagram account (@tarafteh #MishandledArchive) and in the book-version of Mishandled Archive published by Live Art Development Agency in 2020. In ‘A past unknown / not mine / related’, Maddy Costa describes the feeling of looking at the family photographs – clusters of aunties, children stiffly arranged, passport photos, hats, games, fabrics, and so many awkward hands – and imagining one’s own family in similarity or contrast. I am prone to such intimate projections, having access to my family’s photo albums; Špela’s archive takes a more textual form, and we compared notes about the ways that medium impacts the preservation, manipulation, and erasure of family histories. As we browsed through Tara’s archive in the leaves, people wandered into the installation, performance lovers who’d prebooked and park visitors drawn in. A little boy showed off his best weightlifter poses on the tree stump; one person wore an ‘I <3 Peckham’ t-shirt, another had a thunder tube in their back pocket, yet another had a copy of Braiding Sweetgrass in theirs.

‘Hold someone’s hand knowing you will never hold that hand again.’

Any linear relaying of the performance forces it out of its entropic manifestation in the park. I can list details: the mundane and playful occupying of public space; odd juxtapositions of dance-moves with monologues; the choreography of historical dissonances, not only but especially between England and Iran (‘photos dispersed there, there, there, and here’; ‘protestors shot there, there, there, and here’); one trumpet player and four dancers, multilingual singing, smiling, mourning, stargazing, witnessing… The centrifugal force of the work is charged by dispersal – of voices, blossoms, fragments, trauma, seeds, bonds, things that might germinate or infect, depending on how they are handled. As Tara scatters images from her archive in her performances, the photographs become metonyms for diasporic subjects, moving in the hopes of finding a home, moving never to return, moving into oblivion. As the pandemic and successive lockdowns call into question assumptions about homes, households, families, and support bubbles and reiterate the violence of border regimes and hostile architecture, Tara’s performance seems to activate networks and lines of kinship and care and to invite another kind of world-making. Not a world free from loss or pain, but a world in which connections may be set alight from a distance, becoming affective, buzzing, immediate. Audience participation was encouraged in manifold ways, from interacting with the installation to taking part in dance routines to translating scripts. Together we bounced, looked at the sky through the sunlit canopy, and – if we felt comfortable doing so – held hands with strangers. Špela closed the performance by live-translating the following into Slovenian:

‘The story I can’t tell you is that the number of deaths was never confirmed. The pain of loss is never measurable. And the woman sees blood dripping from people’s hands.

As the pandemic and successive lockdowns call into question assumptions about homes, households, families, and support bubbles and reiterate the violence of border regimes and hostile architecture, Tara’s performance seems to activate networks and lines of kinship and care and to invite another kind of world-making.

Tara Fatehi Irani, Mishandled Archive, London, 2021. Photo by Jemima Yong.

She is the daughter of an immigrant who was the daughter of an immigrant who was a victim of war. She is from Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, the desert, the sea, and the mountains.’

The script included a note to bow twice and walk off, reassuring the translator—in our case, Špela—not to worry about it and ‘to be mindful of the uneven ground’ in the woods.

Of course, everyone who attended will have their own special memories of the performance. The porosity, humour, and warmth of Tara’s work inspires varied responses in all its iterations (performances, installations, publications), evident in the essays by invited artists and scholars collected in the book as well as the reviews available to read online. Tara says: ‘They’ve also resulted in friendships and new connections with the writers – which is besides the project but related to life.’ I want to stay with that warm feeling and my memory of Špela standing in the clearing and our conversations afterwards, about family, about distance, about safety, about touch. In ‘What (Not) To Do With Your Hands When You Are Nervous’, Eley (the only good novelist in our group chat) writes:

‘There’s a letter Keats wrote in 1819:

From the time you left, our friends say that I have altered completely, that I am not the same person… I daresay you have altered also – every man does – our bodies every seven years are completely fresh-material’d […] ‘Tis an uneasy thought that in seven years the same hands cannot greet themselves again. All this may be obviated by a wilful and dramatic exercise of our Minds toward one another.

Wish you were here x’

Tara Fatehi Irani, Mishandled Archive, day 285, ‘For the Mantlepiece’, 2017.

Tara Fatehi Irani, Mishandled Archive, day 159, ‘Horizon Is Only in Your Head’, 2017.

We have not been within touching distance of so many loved ones in years; so many are now lost to touch, though they may still be seen, heard, smelled, and communed with in dreams (depending on how we handle death, if ‘handle’ is a verb that can approach grief).

What is the quality of warmth conveyed by WhatsApp, Zoom, across cables, time zones, postal services, incommunicable states of mind and body, the absence of everyday moments of non-being, save the odd photo of meals or pets? What happens to relationships when seeing each other in person involves calculations beyond the direct financial cost—how many people’s health is compromised? What reason is worth the environmental harm; at what point does the need to see each other, to be together here, matter in ways that subsume the material analysis? We asked each other. We probed and provoked each other, got upset, ate and drank more, and kept talking. These questions, these conjectures, may not matter to anyone else but me, or us, which is the risk of this offering, the ulterior openness of its gesture (the hope that you might reciprocate, return). A poignant scene in the performance was based on a conversation Tara had with a woman with dementia in East Dulwich: ‘I don’t remember which way around cos I didn’t write it down. I should’ve written it down.’ What are the different means available to us for remembering, for keeping, for secreting away, and which of these may be translated and sent out again, for another to take and do with what they will? Memory as a gift and a millstone, duty and flight, gambit and rupture.

What are the different means available to us for remembering, for keeping, for secreting away, and which of these may be translated and sent out again, for another to take and do with what they will?

In an article about post-Yugoslav migrant narratives, Špela suggests that ‘intergenerational imaginaries go some way toward transforming the loss of the predictable or normal futures experienced by the older generation into potentially more promising outcomes for their children, restoring some measure of mastery to stories of existential dislocation.’ Whilst her anthropologist’s training demands a specificity that my poet’s licence offends, this analysis of relation, temporality, and storytelling enables a greater understanding of Tara’s work. The performance of Mishandled Archive was rich with characters, voices, anecdotes, gossip, and painful revelations, which I was eager to return to textually. But many of these stories are only hinted at in the book, in the captions or hashtags framing the images, so that the photos and the stories they indicate are presented as cut-outs, shapely redactions. At the same time, storytelling is central to the work, from the originary myth of two sisters known collectively as ShaDi, who phone Tara to share with her the stories and memories they’d been collecting on their travels, to their literary genealogy. Anahid Ravanpoor explains the connecting threads between Mishandled Archive and A Thousand Tales in their speculative lecture at the back of the book: ‘One is the creative method of daily storytelling through working with unofficial, unpublished, and neglected histories. The other is the reincarnation of Shahrzād and Dīnāzād […] as ShaDi’.

Book cover of Mishandled Archive by Tara Fatehi Irani, published by the Live Art Development Agency, 2020.

Tara gives us what she chooses to give us, and we can choose whether to accept the offering. My desire to know more about the stories is a desire worth challenging, as Joe Kelleher reminded me prophetically in the online launch of the book: ‘Let things be quiet in their context.’ That context is there, there, there, and here. Researching this essay (aka indulging my nostalgia), I find an old photo of Špela, Eley, Prue, and I posing in a nativity scene; as Mary, I wear a scarf with a bacterial pattern that Špela donated to me and I happened to re-donate this month. Eley sends us a video of Ambrose gurgling to House of Pain’s ‘Jump Around’, fulfilling Špela’s and my godparental need for regular updates. My mother asks a dear friend to knit a woolly hat for Ambrose, outsourcing her godgrandparental duties, so I start sending Neeta Aunty photos of Ambrose too. At the online launch, surrounded by her friends and family, Tara said that ‘storytelling everyday saves you,’ which I wrote down promptly because it seemed essential to remember. A flower report from Dolsko arrives in the group chat. Smiling Faces with Hearts float into my mind in a wilful and dramatic burst.