Video still from Mun koti / My home, 2021

Marja Viitahuhta is a media artist and filmmaker, who lived her youth in Inari and her adult life in Turku and Helsinki. Her first film 99 Years of My Life was edited by Azar Saiyar. They also have had exhibitions together and in collaboration with installation artist Ida Palojärvi.

“Taking a pencil in their hand for the first time, the child begins to draw and only later names the product of their drawing. Gradually, in accordance with the level of the development of their activity, naming the drawing moves first toward the midpoint and eventually to the beginning of the action. At this point, it begins to define the whole action and the purpose that it realizes.”

— Lev Vygotsky: Thinking and Speech (1934), an excerpt from Azar Saiyar’s press release for My Home and Roses

Azar Saiyar’s portrait by Katri Sipiläinen, 2022

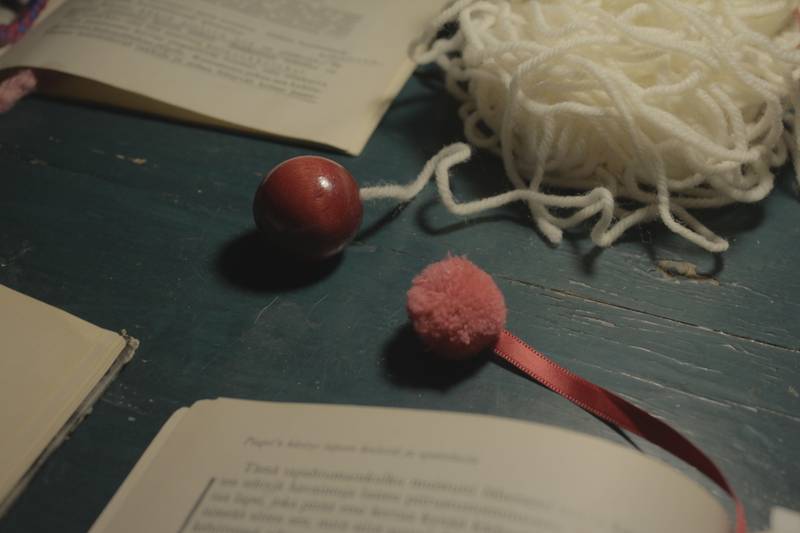

Since Azar and I are friends, I can only indulge in approaching her art from a very personal point of view. Her films live in me from before she makes them as well as afterwards, like a mixture of the work itself and the conversations we’ve had. My Home and Roses is the title of Azar’s October exhibition in gallery Maa-tila, where she has presented two moving image works My Home, an experimental film with fragmented memories of childhood and adulthood blending, and Roses, a subtle and straightforward video with images of blooming and withering roses, with music by Joonas Kiviharju, Saiyar’s long time partner and collaborator. There was also an installation with books, other objects, and images on a table entitled Worktable between the other two works. The Worktable is Azar’s way of making some parts of the process visible by putting together some of the things that have been with her along the way. The photos, the bookmarks, and the lamp made me think of the table as a prop, a set that binds the videos together, allowing us to look at some aspects of how the video works. The books are opened up so that they form a collection of fragments, with English translations of her selected citations attached to them. The installation is easy to approach - the visitors can sit down and freely touch and browse through the books.

MARJA: The word “home” is not only in the title, My Home and Roses. It is also there as a concept: what and where is one’s home?

AZAR: People make home. But that is only partially true. You can feel homeless, even if you had the most wonderful and caring people near you. But to comment your thoughts about the installation of The Worktable at MAA-tila, I like to mix things up and experiment with different categories and structures. The collection on the table was an attempt to form a private educational archive of many things; books of educational theory and pamphlets, John Locke, Maria Montessori, and Lev Vygotsky, etc., entangled with the everyday, such as the self-made bookmarks, snapshots, and my mother’s drawing of a flower with the letter K. (Kukka is the Finnish word for flower). There were also other things starting with the letter K.

I often get curious and feel that it would be lovely to hear more, to have you shed more light on the stories you have in relation to these fragments. And yet, at the same time, I realise -and this is what you also stated in your press release- that you are not striving for coherence and unified entities, and my initial need for explanations might diminish as I let myself slow down and just perceive what’s on display.

I am interested in language. I question language. I often feel that naming things too clearly, opening them up as if they were on an operating table, does not speak about the things I am trying to reach, but puts them in certain categories, forced within a certain structure that is not my language. It feels like a violent act.

Installation view of Mun koti / My home, 2021 at MAA-tila

Installation view of Mun koti / My home, 2021 at MAA-tila

My Home is a complex work, yet simple to follow. It feels like you want to dodge the obvious and avoid blandness. Is it about aesthetics? Or something else? Do you have an urge to challenge your audience?

On the contrary, I have faith in the spectator. I believe that we can recognise things from structures or stories that are strange to us. On some level, it’s always about aesthetics, especially when something seems natural and authentic. In documentary footage that appears objective, the style is an aesthetic choice. What you have been exposed to shows in your work. For example, if I had started making video art ten years later than the time I began, I would probably do different kinds of artwork than I do now because I would have seen other things right from the beginning. So, even if I consider form to be part of the content and that the structure of each work is purposefully chosen, I’m not sure to what extent I can state that I’m creating new manners of approach and how much, in the end, I’m just stuck in my time. All I can say is that I try to find ways to create pieces that feel meaningful to me at the time they are made.

My Home extends a continuum of works, especially the films Laila’s Apple and History Bleeds Under Your Fingernails. I see them all as parts of a process during which you have been involved with specific themes: education, parenting, school, remembrance, history, and the difference. There’s also the question of how to speak to one’s children about the problematic aspects of history. For example, in History Bleeds Under Your Fingernails, you talk about forcing left-handed people to use their right hand. And the question of expectations has been there as well. What are your thoughts?

Yes, they’re part of the same process. I feel driven towards topics like upbringing, learning, or growing up, not just as an artist but as a person. They are things that I want to spend time with. I stare at different materials. I try to move inside them. Currently, I find this theme question a little difficult for me to think through, to keep the perspective where one finds a theme and then explores it. When one says, for example, “I am going to make art about education,” To have that gaze that is somehow top-down. It is a question of how an artist names what they are doing. It is often expected of artists to be capable of compressing their practice into a few well-defined sentences, even when the process has not yet produced the actual artwork. For example, when you need to convince someone to get funding, diving into a topic is how it often goes for me as well. When I get excited about something and want to understand better how it works, I get the need to cut it into parts and arrange it. But I’m interested in finding ways to create a particular distraction, some drowsiness, and leave space for different ways of experiencing. So that life would come between the gaze and the theme.

Your work appears to be created through an associative process as well as the collection of materials and research. In your films, there is a certain sense of weight, a touch of meaningfulness that comes across even when you do not explain your choices or narrate the stories behind each choice. I approach the imagery and sound in your films as if they were poetic metaphors. I am recalling the very beginning of My Home, with a television presenter from the 60s who teaches children how to play correctly, in a focused way. I am thinking of its final picture, where the moving landscape is viewed covered in snow. These images mix with the everyday imagery (and when I say “everyday,” I immediately question whether they are truly mundane because some of them feel staged, even momentous.)

I dedicate time on a regular basis to a variety of activities that I believe are related to what I am doing. I enjoy the fact that I do not know exactly what’s coming. I think that my relationship with my artwork is often like a viewer’s relationship with the images. I feel more like a spectator than a maker.

When one says, for example, “I am going to make art about education,” To have that gaze that is somehow top-down. It is a question of how an artist names what they are doing. It is often expected of artists to be capable of compressing their practice into a few well-defined sentences, even when the process has not yet produced the actual artwork.

How about the editor in you? The person who arranges, combines, and frames.

During the editing process, the work evolves. It is a lengthy period. I begin it early on, without a script. I do write things down during the process, but I always have edited my imagery ready before the text. Then I decide what parts of the writing process I will incorporate into it. I film images along the way. And maybe once every couple of years, it’s like “I figured out that such a picture would be nice,” and then I get my family involved in the project, and we think together about how to realise the image, and then we just put the camera on a tripod and shoot it on a Saturday afternoon.

You often have a text or a voice-over that narrates. My home has voice-over narration with a very personal vibe. The sound of the voice-over is read through a vocoder, and the overall sonic atmosphere created by Kaino Wennerstrand affects the entity with a mixture of lightness, playfulness, and intimacy. There are distancing elements; there are aspects drawing you closer and oscillating back and forth. Is personality an important aspect for you? Are your films conceivable as autofiction or some sort of expanded self-portraiture?

I don’t see my work as self-portraits. Maybe my earlier Helsinki-Tehran was partially like that. Sometimes my own experiences are the starting point. However, the narratives in my work are often a combination of several people’s memories and knowledge from different generations, told from various perspectives.

Speaking of personal stories versus a multitude of experiences, the voice-over in Laila’s Apple initially sounds like a monologue, spoken by a single individual. But it is in fact based on several stories and multiple voices -interviews with women, actually. As a viewer, you realise that the depicted experiences happened a while ago.

It is interesting to notice how some of the aspects of “what it used to be like” still appear in the mundane and everyday. For example, how children in groups are handled and moved from one location to another in a manner that is very similar to, say, 100 years ago. The punishing system of school has changed, but the everyday routine is still the same. And also this idea of old-fashioned school discipline, how it affects how we see school, even when we have no personal experience of such a school. We know what authority means and feels like, even if we did not have to undergo certain methods ourselves. It’s part of how we think about school, even if we have no personal experience of physical discipline.

In Laila’s Apple, we never actually see the whole original picture, just details. It feels condensed: just looking at that one clip over and over again and framing new compositions out of it.

In some ways, school is similar; you direct the focus and actions.

Installation view (detail) of Työpöytä / the Worktable (2021) at MAA-tila

Installation view (detail) of Työpöytä / the Worktable (2021) at MAA-tila

You are also interested in the transgenerational phenomena?

Yes, and archives are one way to bring into the narrative something that is not your own. The archives have the ability to carry within themselves the idea of collective memory and shared experience. I am interested in the lack of certain experiences in that common, shared memory -that which has been so marginal, so tacit knowledge, that pictures, words, or language do not exist to depict it. Things that get forgotten due to the need for a pure idea or a pure story -like when speaking of nations or identities; and impurities when approaching such concepts. I like impure, non-monophonic narrations.

Your works have the tendency to deal with the marginal, against the backdrop of the grand narratives of history. Do you see your works as political?

I am interested in political issues, such as who has power or how it is distributed or exercised. Who gets heard? Who has the opportunity to realise themselves? To live? Whose needs are met? Probably some of these interests also flow into my art. This is of course a question of what the word political means in the context of art. Art does not have to be efficient, it does not have to stay effortlessly/smoothly inside one dogma.

You often have images in your films that catch the ball, so to speak, from text and pass it on to another part of text later in the film. This is also done with sound and music. The conversation between imagery, sound, and text does not only happen in a linear way but creates contrasts and layers. How do you make this conversation happen?

The relationship between image and sound is very important to me. I’ve been lucky to have been able to work with visionary sound designers-people whose vocal thinking and understanding are sharp and deep. Collaborating with a sound designer is the point where those pieces eventually emerge for me. Overall, I am drawn towards collaboration, sharing, and mutual learning. I think collaboration is not easy, but it can be learned. I don’t make my movies alone. I create them with a team, and that’s why they are not just my vision or my films alone. Different people bring parts of their own thinking and experience to the work. When I am working with archives, I know that I am wielding power there, making choices over how the archive material is shown and used. I try to spend time with it and have a conversation with it as if it were a collaborative process. I’m currently working on a new project where sound archives are the starting point. I have never before done that, starting with just sound. It’s exciting to see how it turns out. I don’t know it yet myself.

I am drawn towards collaboration, sharing, and mutual learning. I think collaboration is not easy, but it can be learned. I don’t make my movies alone. I create them with a team, and that’s why they are not just my vision or my films alone. Different people bring parts of their own thinking and experience to the work.

Installation of Ruusut / Roses (2021) at MAA-tila