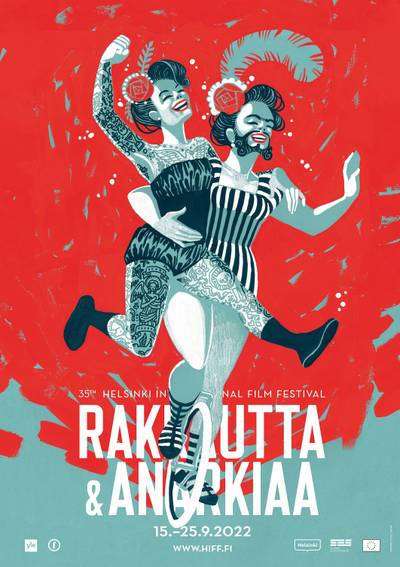

Plantasy exhibition promotional poster

Hanan Mahbouba (b. 1990 San Jose, CA) is a writer and filmmaker. Her work focuses on storytelling that explores the space between belonging and otherness. Hanan’s interests, in both film and text, revolve around the distillation of the singular moments that end up framing our understandings of ourselves and others. Recently, she wrote and directed the short film Fatima Falling and is currently at work on her first feature.

On a freezing night at the beginning of December, Plantasy opened at Vaasankatu 15. The opening was so full of people, support, and love that you literally could not encounter the art. Plantasy is an exhibition commissioned by Feminist Culture House1 as the inaugural iteration of their curatorial nestee program. They invited Gladys Camilo and Jonni Korhonen to curate the show, providing mentorship and organizational support as needed. Gladys and Jonni, in turn, invited artists Ama Essel, Aava Eronen, Ignata Elana, and Viljami Nissi to create new works around the themes of mutual care, play, and joy.

Plantasy, or “a garden for dreaming” centers around the ideas of togetherness, community building, and the realization of utopias. These kinds of concerns are currently very popular with art spaces as they all vie to create, or at least make the illusion of hospitality, safer spaces, and non-exploitative working conditions. The actualization of these goals seems very simple yet challenging at once because collective work is complicated when an attempt is made to make space for everyone’s needs and desires. The paradox comes because many of the components of care work often seem obvious: ask questions, engage in active listening, pay people, don’t charge rent for a gallery space, and on and on. Yet it somehow seems very difficult for larger institutions, in particular, to deliver on these goals.

The significant elements of fruitful collective work are strong communication, commitment, support, and vulnerability. In my conversations with Gladys and Jonni, it was clear that, for Plantasy, these goals were created for action. This actualization took place on two fronts: in the creative and conceptual thematics and in the practicalities of the working structures. Creating a space for vulnerability only works if everyone in the group is devoted to it. For the artists, this meant not only dedication to their individual works but a commitment to invest time and care in each other. To build this, Gladys and Jonni hosted monthly dinners throughout the project where all four artists were present every time. This trust and openness were also cultivated through studio visits, consistent group communication, as well as space for private, more intimate one-on-two conversations between the curators and each artist. In other words, as Jonni put it, the working structures functioned as a “how-to-build-a-friendship” primer.

Image: Aava Eronen

With every work or project, there is a world of difference between the artist’s dreamed-up vision of what the final result will look like and reality, which comes along and changes the fantasy entirely. Neither good nor bad, this transmutation is simply part of the art-making process. When you work in collective structures, the complications that arise from the mediation of a dream into reality are multiplied by the number of people present. There are many wonderful things about collective work. An essential, perhaps sometimes overlooked, element that Gladys brought up is accountability, and that within a structure, there should be space to admit when you have made a mistake and then to be able to move on from it. Being in a state of constant learning and adapting is a big part of vulnerability.

This particular exhibition occupied a unique space within the art scene of Finland because its working structures were informed by Feminist Culture House (FCH) and Gladys and Jonni and then enacted by all eight members of the working group. As an institution of the Helsinki art scene, FCH’s devotion to studying and working with the realities of care work through peer support groups, workshops, and transparent contract-making, among many others, was the soil from which the nestee program sprung.

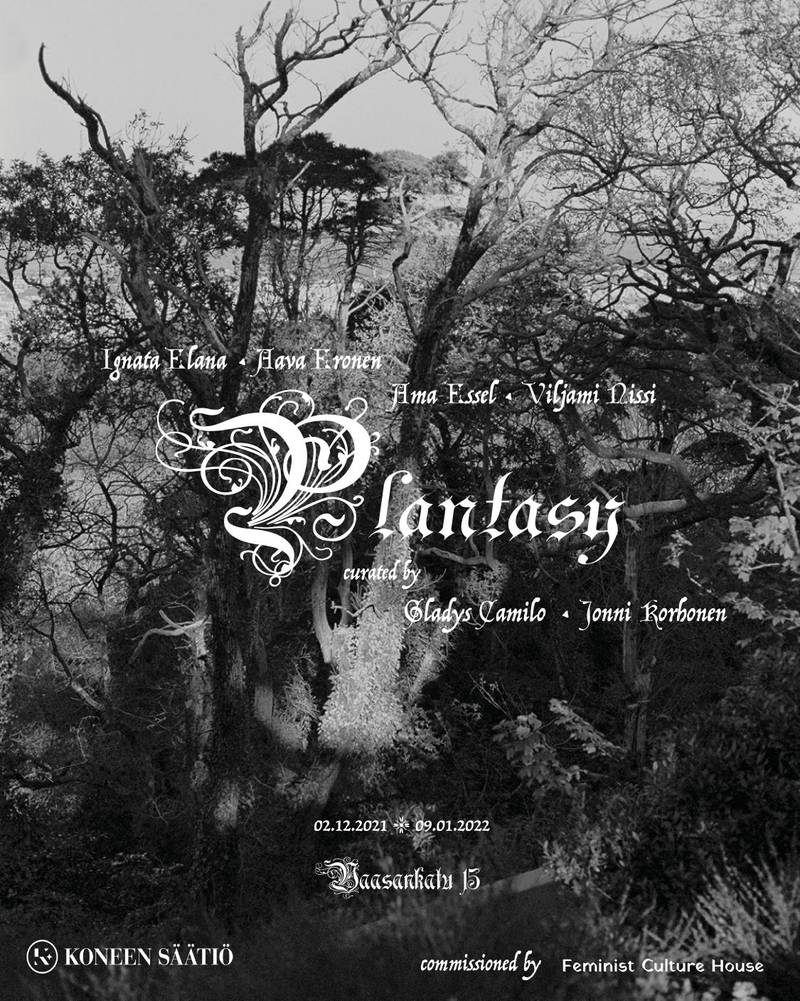

Visualizations of a utopic garden adorn the space. From the ceiling hang drying flowers and plants in various stages of preservation. Directly below this, in the center of the room, is a pile of soil ringed by potted plants, all in an ode to growing and sharing. Overall, one can be tricked into believing they are in a tropical environment, a greenhouse of warmth and joy with red and orange lights emanating from the corners. The small space unfurls. A perfect square is shattered. While some of the physical flower elements were nice and certainly reinforced the unity of the exhibition, this literalization of the theme made it, at times, difficult to connect with the artworks individually. They accentuated that though one specific artist did not author these elements, they were there because everyone agreed to them, visibilizing a kind of trust that comes from a secure bond.

Image: Jonni Korhonen

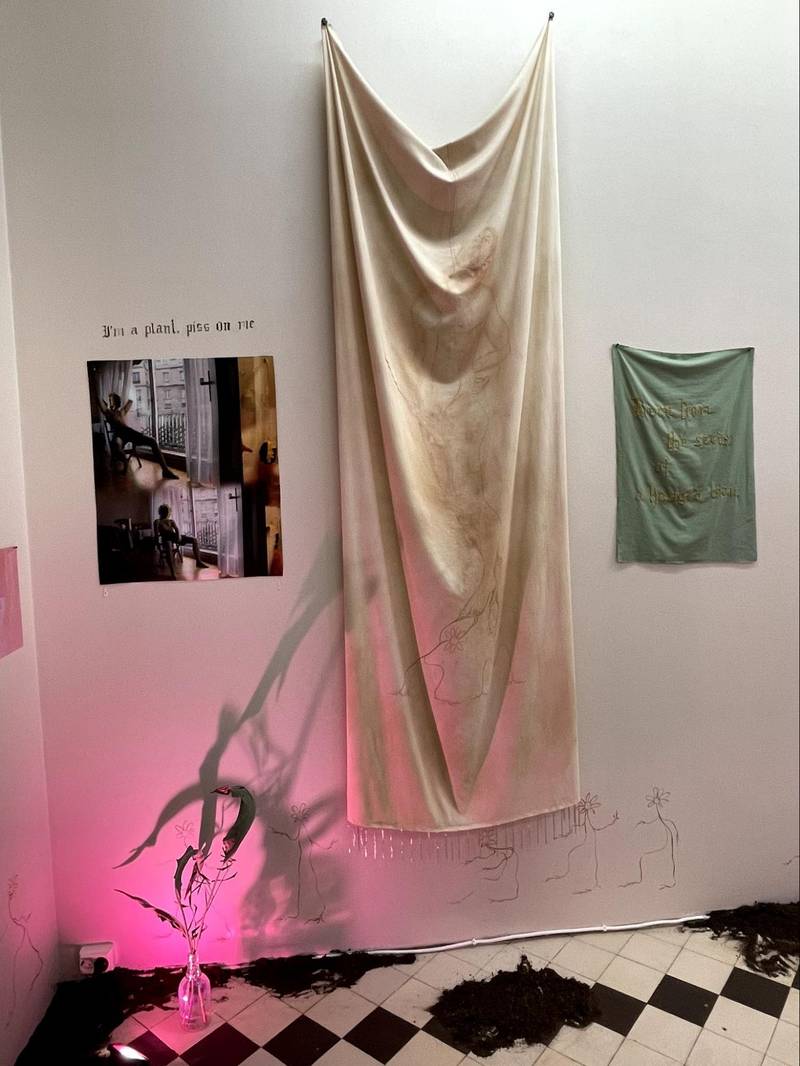

Viljami Nissi’s practice is informed by a reworking of folklore and legend. Here, the works are all different iterations of a mashup of the biblical creation story and a myth about the origins of the mandrake plant. The narrative created by Nissi unseats “man” from the central role of importance. In the Bible, God gives Adam and Eve “every seed-bearing plant” to provide food for them. But here, “man” becomes food for the flowers when he disobeys God’s will and kills himself by hanging. In this recasting, the traditional narrative that centers the very hetero Adam and Eve’s plans for procreation is disrupted by the man’s decision to sacrifice himself, which benefits the planet. His actions result in him becoming a contribution rather than depletion.

In the physical work, a hanging draped cloth shows the hung man in the throes of emission. He loses his life and, though according to legend, the “human juices” released during a hanging will result in the growth of a mandrake, here it very much appears like an ejaculation. The penis is erect, pointing upward as tiny seeds of pearl spill out in gorgeous, measured decadence. The positive depiction of the cum is also suggestive of sexual auto-erotic asphyxiation. The works center around play and sexual fantasy rather than death throes. The sweetly rendered baby mandrakes pull at the hanged man’s toes, like baby birds begging for food. They beckon, bringing him to his final resting place. The work is also a take on the “Shroud of Turin” or “Holy Shroud”, said to have been the burial shroud of Christ after his crucifixion.

Image: Hanan Mahbouba

Image: Jonni Korhonen

In the series of photographs, “Transformative Soil”, by Aava Eronen, the subjects’ gaze is always direct; everything is clear and strapped in. The models are unapologetic, and their stark stares indicate that they are comfortable being confronted by the camera. The setting of all the images is natural, relating to idyllicism, peacefulness, and calm. The main images are grouped into pairs, inviting the viewer to compare them. The same person wears a dog collar in one image, and in the next, they hold a many-tasselled whip. The person inhabits the foiling identities of dominance and subjugation yet chooses to be defined by neither. The natural setting suggests this is the natural order of things—nothing must be forced; it’s fine to be both and many.

The simplest form of joy often comes from togetherness. There is a cross-pollination here between the photographer and their models. Creating an environment in which the subjects feel at ease in their vulnerability as nude is an extension of the play and non-rigidity seen throughout the exhibition and one that ripples out into the photographer’s community. The same figure appears across the main works, in the third and largest photo in the series they are perched atop the hip of another person who is reclining in nude. There is comfort and familiarity between the two. The collection of images asks us to consider the person from many different angles, perspectives, settings, and roles. Allowing them to be who they feel like being at any given moment—a rather sweet provocation.

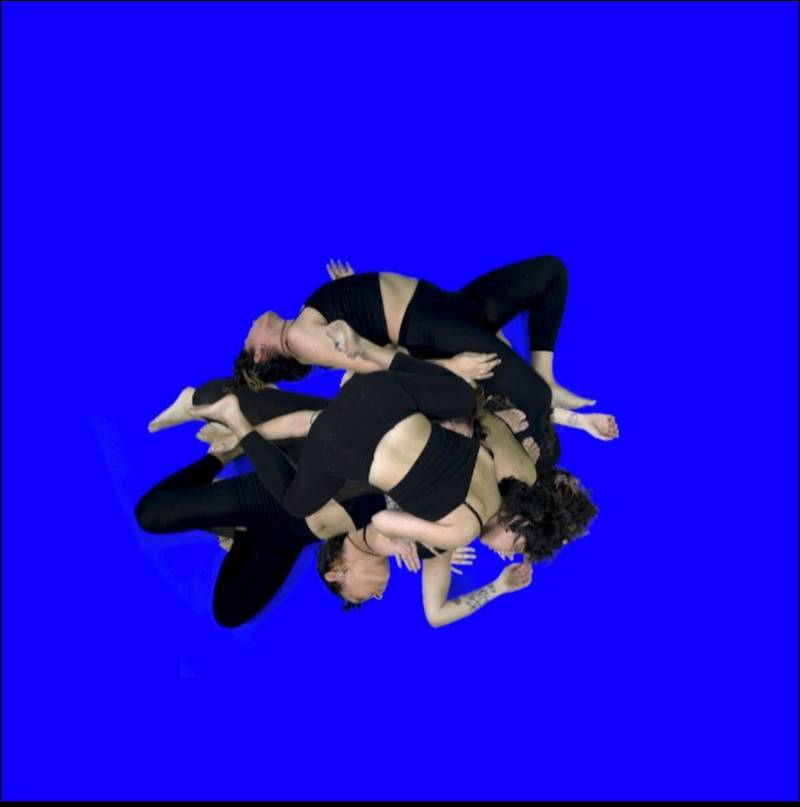

Still from Until Vanishing Flesh by Ignata Elana

Ignata Elana’s video work “Until Vanishing Flesh”, shot over ten months, freezes moments in time. Though its subject matter meditates on what it means to live in a body, physicality permeates and suffuses everything like a drop of pigment in a water glass. A critical component of care is time and attention. Slowing down and being present during an experience allows the process to sink in deeper and emotional clarity to develop. But if the experience is tender or difficult, there is a strong temptation to rush and skip past it. This work chooses to remain present and to deconstruct the journey.

The film juxtaposes video diary documentary footage of a non-surgical cosmetic procedure with a hectic infusion of abstracted self-portraits and shot styles. In one flow, Ignata dances in cyclical pulsing actions, multiplying herself on the screen in isolation. In a non-abyss, not a black hole but a space devoid of any texture or locality, the body’s existence in a space and context changes. Where the body is placed in what frames also change its reality. The body in isolation relates to an important foundation of the exhibition as a whole. If all these artists and their works were placed in a separate cocooned environment, how would it feel, and what kind of work would it beget?

The poetic text that appears in the installation uses both the abstract and the concrete to stretch and distill the moving images. The lyric poem dwells on and in the body. What is there, what is desired, and what is to come? Hark, a revolution, spoken from every street corner. Yet it’s a personal one, like the soft caress of a cotton ball soaking up the after-effects of change. There is a hierarchization of needs, a questioning of what is important. Analysis and categorization of conditions that shift between want and necessity. What constitutes the body anyway? What are the physical implications?

In Aava’s photographs, the setting stays the same while the bodies and people change. In Ignata’s video, the “place” of the images shifts as the body traverses through time and spaces that are real and imagined, the stuff of dreams and nightmares. The pain and blood of the procedure cannot be ignored or diminished. They are physical proofs of pain, though not necessarily hurt.

Image: Jonni Korhonen

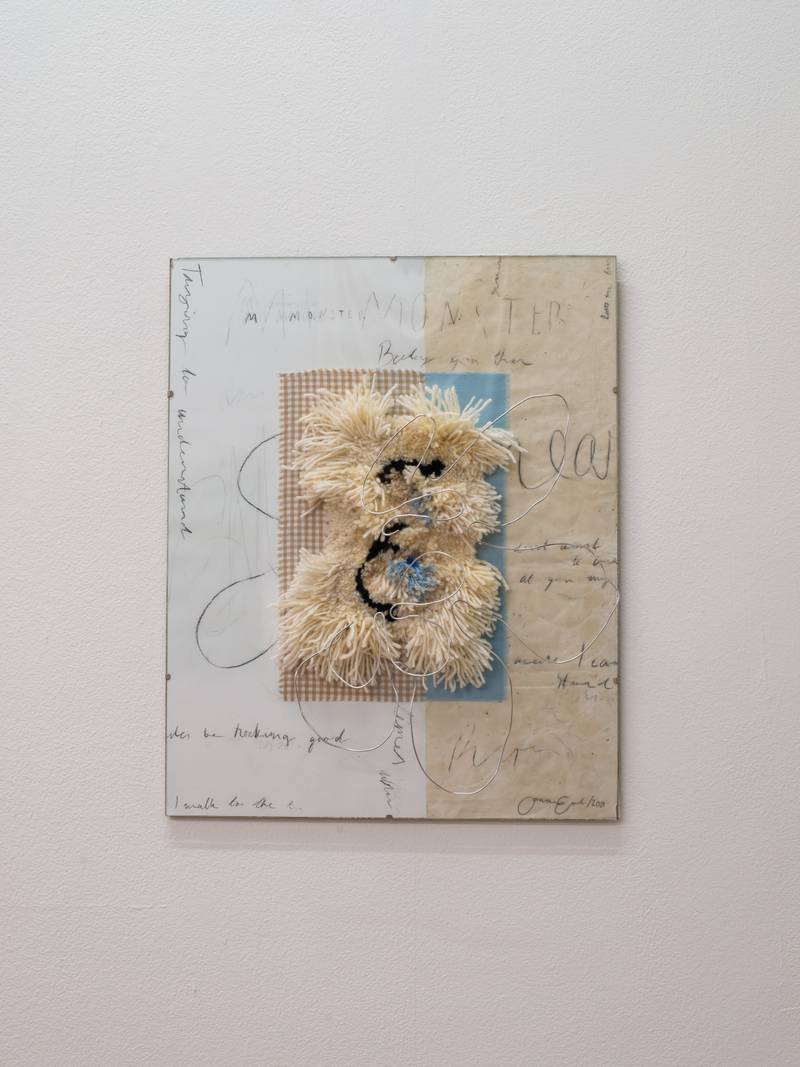

“Sweetheart Delusion…?” Ama Essel’s rya technique yarn installations are the most abstracted of the works and thus provided me with an opportunity for playful imagination. The works look backwards in history to imagine a different present. This reexamination of traditional craft techniques explores a desire for the rya to not function as just a mascot of the domestic. The spirit of experimentation and play arises from non-rigid expectations. The interplay of textures of wool with metal and wood with glass provided a clear tactile binary for the mind to wander along while also giving space to deviate. The oppositeness of the materials reinforces what’s unique about the other.

As a craft-scientist, Ama examines the implications of rya, a very traditional and gendered craft widespread in Finland, and the precious family artifacts handed down throughout the generations. These works, on the other hand, are rough, both physically and metaphorically. Similar to Viljami, the text that accompanied the yarn installations was intriguing and alluded to a larger body of work and research around the shattering of existing lore, myth, and tradition.

The traditional rya wall coverings invite you to run your hands through the thick woollen rows. Whereas these installations have rough-cut; wooden objects or metal bands stuck in them. The wood is not finely cut, there are rough edges and non-uniform shapes and lines. It’s not meant to be perfect. These works intentionally serve no practical purpose. They are art objects intended to adorn, not to keep you or your hearth warm.

Collectively, it seemed that identity and how endlessly unique every person is, containing multitudes of shimmering and ever-changing facets, was the overall theme, and the garden the home for it. In most of the works, the body and its textures and feelings are centralized. This exhibition invites the viewer to dwell in reverie on fantasy and hope. If what you are seeking in life doesn’t exist, there is the knowledge that it can, even though the iteration might be different than what you would have expected.

Tendrils of each work bleed into each other. The soundtrack from the video, “Everytime, I close my eyes…”, spills out of the headphones and into the rest of the space. The “piss on me” mask is placed in the corner by the hand sanitizers and the exhibition texts. The photos are reflected in the glass of the yarn installations, and the living plants unite–all physical representations of what one assumes was an agreement of mutual respect and collaboration. In these refractions of the self, utopic dreaming takes center stage.