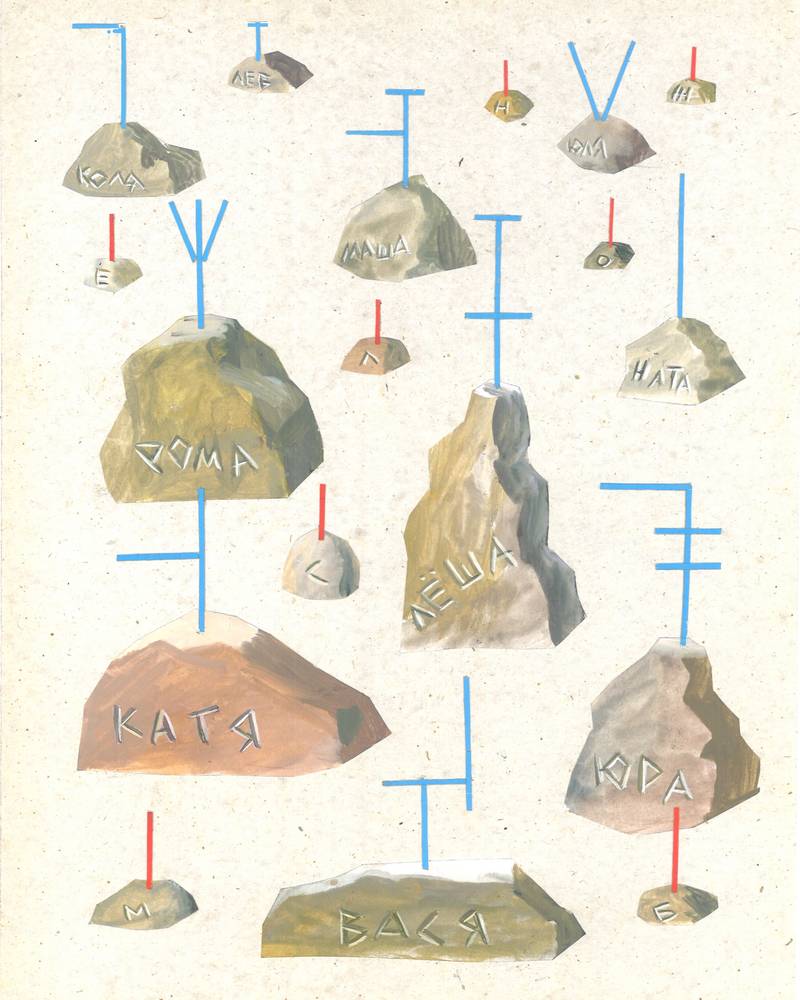

Roman Sakin, Portraits of Russians who Left from the War for Armenia, 2022

Adel Kim (b.1987) is a curator, manager, and researcher. She received an MA in Art Studies from Hongik University (2018) and MA in Cultural Management from Manchester University and Moscow School of Social and Economic Studies (2020). Currently, she is a researcher in the Reside / Sustain: Finnish & Russian experiences / initiatives / practices project.

As of September 30, this text was mostly written before the announcement of partial mobilization in Russia. The situation is changing quickly and drastically: many people, mostly men, not aiming to participate in the war, are urgently fleeing from the authoritarian militarist state that the country has turned into; the rumors of a complete closure of the inner borders are already in place. At the same time, European neighboring countries, including Finland, shut down land borders for tourist visa holders, leaving fewer ways to escape. In contrast, in Kazakhstan, Tadzhikistan, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, and other countries of the region, volunteers open humanitarian support points for Russian people fleeing mobilization.

So far, no art institution has proclaimed any solidarity with Russian artists.

As the process is still ongoing, I decided to leave the text as it was because it is already a footprint of the past. The present is unclear, and the future is unfolding before our eyes.

1

The owner of one bookstore in Helsinki, with whom I started chatting casually while making a purchase, was surprised that I paid only with cash. I said, well yeah, you probably know the news about Russia and how it goes. Of course, he said, and it’s a big pity. However, he continued, it will be a lesson for all of you.

This text considers a variety and mismatch of opinions expressed by those who, despite coming from different contexts and perspectives, are all under sanctions and associated with the arts in Russia. I write this because many still share the position of the bookstore owner mentioned above: of a didactic or even pedagogic urge (although, as it is important to emphasize, my personal experience in Finland has been only positive and empathetic, with that one minor exception). At some point in the current war, a wide international audience obtained the right to judge who should be punished and how, who deserves what, and why. Although we are all less or more ordinary people in different countries suffering from the consequences of the insane actions Russian power holders keep on producing, there is a part, and a privileged part, who can decide for the others what is to be done while closing their eyes on the details, context, and real human lives.

To the rest of the world, you are a coward who cannot stop the bloody dictator and thus supports him. As you’re unable to speak out your real position, you pick your words carefully, use euphemisms instead of calling things their real names, and stay quiet in the face of injustice and open aggression towards a whole nation, you also betray yourself.

To clarify it from the beginning: as a citizen of Russia, I cannot be distanced from the topic; it is personal, and I am an interested party. I am neither neutral nor objective. I am aware that I have unexpectedly become a member of an unwelcome group due to a formal ground (my passport and nationality), and I feel compelled to act.

On the morning of February 24, all talks about the “soft power of culture” and “art changing the society” became merely bullshit, and the realization of this came as a slap in the face. All the soft powers were easily smashed by an aggressive, bullying action. That morning, I witnessed the craziest thing in my life, something beyond my imagination. Although talk of it was in the air for a while, and the slow conflict had continued for eight years already: Russia, the country I was born and lived in, has attacked the sovereign state of Ukraine.

From that moment on, neither previous experiences nor future plans continued to matter or exist, and this thought was hard to grasp. Things got hectic. Russian citizens who disagreed with the leading foreign political course faced various political oppressions within the country. The laws were changing daily, and pronouncing the word “war” or making claims for peace was considered discrediting the Russian army or “fake news about the special military operation,” punishable by a fine or up to 15 years of imprisonment. At the same time, the country faced multiple economic sanctions from various European, American, and Asian countries, including the suspension of businesses, removal from the SWIFT bank system, a ban on selling euros to Russia, visa bans, and other restrictions.

Sanctions as a phenomenon are nothing new in the Russian context. They have become a daily reality after the criminal annexation of Crimea and unconfessed military actions in Eastern Ukraine in 2014. However, at that point, most of the sanctions related to individuals with political power and influence affiliated with Putin or his government. In spring 2022, for the first time, the effect of the sanctions was expanded to affect civilians under the motto “let them think again and overthrow Putin.” To the rest of the world, you are a coward who cannot stop the bloody dictator and thus supports him. As you’re unable to speak out your real position, you pick your words carefully, use euphemisms instead of calling things their real names, and stay quiet in the face of injustice and open aggression towards a whole nation, you also betray yourself.

Since the beginning of the war, frustration has evoked a circulating delegation of responsibility. European citizens call out, “Russians, go to the barricades and protest!”. Ordinary Russians blame oligarchs who have power and lose money for being unable to change; oligarchs might have someone else to blame. A recent tendency among antiwar Russians is to criticize Western countries for supporting Putin’s clique for all these years by buying oil, gas, and coal from Russia (I assume because they care about their citizens, not about Russia). Russians who have left the country blame the ones who stayed; the March ‘wave’ of expats is unhappy with the September one. European neighbors frequently close their borders, claiming that Russians should deal with their own problems. The consequences of the war are becoming more palpable, and people worldwide are demanding that others give them back their normal lives. The reality seems to be way more complex and tangled; the war and dictatorship could not be overcome by only one group of people and with only one tool.

Simultaneously, we witness a constant change of demands regarding relationships with Russian cultural practitioners: first, for them to leave the country if they are against the war; then, for international institutions to suspend the relationships with the Russian side and cut any payments for Russian artists so they don’t pay taxes and the state cannot produce bombs (although artists are obviously not the primary taxpayers); and most recently, to ban their travels (with the new rules, it is most unlikely that a Russian artist would be able to go to, let’s say, a European residency). These demands have the possibility of being quite self-contradictory as the prevailing rhetoric changes.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine should be stopped as soon as possible, but how? The world is showing great solidarity with the suffering side, but should it go hand in hand with humiliating, neglecting, and demonizing Russian passport holders? Can the problem be solved by putting more limitations and borders on ordinary citizens already oppressed by an authoritarian state?

2

Sometime in the summer of 2022, Helsingin Sanomat ran a new advertisement at the airport, the Kamppi shopping mall, and other locations, saying, “But in our country, we do talk about war” (А в нашей стране о войне - говорят). Aiming to be a statement of a free people’s state, at the same time, it reminded me of a kid’s squabble, which is supposed to evoke jealousy in the opponent (“my older brother is very strong, and he will beat you”). I did feel jealousy, just like a kid.

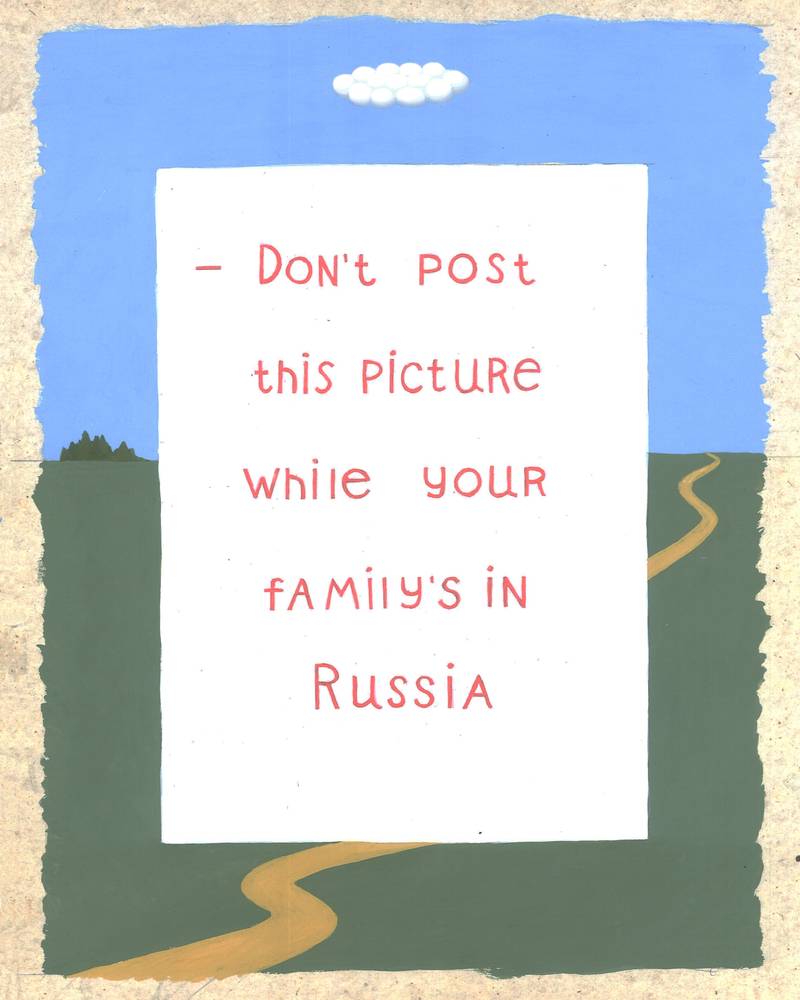

I am happy to have the ability to talk about war here, to call it war instead of whatever euphemisms are legal in Russia (“the situation,” “the conflict,” etc.), and to be able to yell out loud “No to war”. However, freedom of speech remains an out-of-reach privilege for many who would like to do the same but cannot or do not want to for a variety of reasons, including fear of being investigated or jailed, physical threats of torture, and anxiety about their partners, parents, and relatives. It’s great that there are countries that allow speaking your mind safely; my question is why it should be delivered to others with bragging superiority. Why don’t Russian artists speak openly about war? In general, as described before, they face the same threats of being convicted for discreditation – this law works unpredictably. Before it was passed, one of the first reactions of the artistic community was an open letter of 17,000 Russian art workers condemning the war (the text and names of people signed are no longer available in the original source); This letter caused dismissal for some of the undersigned who worked in Moscow institutions like MMOMA or the Museum of Moscow. Many art workers went to spring protests in Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and other cities, although it was illegal and violently suppressed by OMON (riot police). However, some artists keep speaking openly online at their own risk. Some decided to protest within the professional field and canceled all relations with state institutions or even all art institutions in Russia. There was a statement of silence initiated by artists Antonina Baever, Alina Gutkina, and Anastasia Potemkina, who refused to be involved in any artistic practice until the freedom of speech was available again. Although all of this helps the artistic community in Russia to see that there is solidarity between them and that they share similar positions about the war, from the outside, it looks like the community is silent and inactive.

At the same time, for the state, contemporary art is mostly an unimportant obstacle to be moderated. For example, artists participating in some exhibitions must be screened for their political views and social media activity (in the well-known case of the Exhibition Halls of Moscow network run by the Moscow City Department of Culture; this rule was later repealed). People from FSB or Center E (a special division dedicated to extremism) come to exhibition openings, cultural spaces, conferences, and symposiums in search of signs of extremism and anti-war activities. Typographia, the contemporary art center in Krasnodar, faced closure after being recognized as a foreign agent.1 Thin citizens, the graduate exhibition of joint Garage MCA and Higher School of Economics MA program in contemporary art curating, was shut down by their host institution, MMOMA, the day after the vernissage due to some political content for which the host did not want to be held responsible.

Why don’t Russian artists do activism against war? Not hearing about something is not the same as it not existing. Paradoxically, we must keep silent about antiwar underground initiatives that are quietly developing in Russia right now, as anything available online is available to oppressive powers and authorities. It would be beneficial to share this information and spread the word, but who can guarantee that the police will not knock on these artists’ doors the next day? For example, in the recent Chto Delat group and the anarchistic art group Party of the Dead case in Saint Petersburg, their members had to flee immediately after such police visits or prevent such.

Another problem is the questionable efficiency of straightforward activism. Even if one puts graffities and antiwar stickers (for example, as the Vesna movement widely does), replaces price tags in a supermarket with antiwar messages (see Sasha Skochilenko’s case), or tries to convince others about the real state of things, this would not help as the propaganda has already had its effects. These risky activities look more like a fight with one’s own frustration.

Not hearing about something is not the same as it not existing. Paradoxically, we must keep silent about antiwar underground initiatives that are quietly developing in Russia right now, as anything available online is available to oppressive powers and authorities. It would be beneficial to share this information and spread the word, but who can guarantee that the police will not knock on these artists’ doors the next day?

Why don’t Russian artists just leave the country if they are against the political course? Indeed, fleeing somewhere is the first thought in cases of threat and oppression. This is what many of my friends and acquaintances did, and it is something I personally was able to do. But let’s be honest: relocation is a privilege. 69% of Russian citizens have never traveled abroad due to lack of interest, modest financial situations, or even poverty; only 30% hold international passports that allow traveling abroad. Moreover, people have their old parents, kids, house loans, no savings, and just their whole lives in their home country. Relocation needs stable grounds such as visas, residence permits, employment contracts, and the right to work, which are not easy to obtain. Income is a major consideration—where can you get it in another country, especially as an artist? Many are looking for ways to relocate; some make it successfully, but it is much harder in practice than in words.

At the same time, the whole number of dissenters could not be evacuated. Moreover, among them, there are artists with a principled position of staying in their country. For example, Anastasia Bogomolova, an interdisciplinary artist from Yekaterinburg and an author of a Telegram channel called Oshibki residenta (Mistakes of a resident), comments on her decision: “I feel responsibility for topics I work with, for creating a common language of art that helps express what is barely reflected. This confirms to me that I need to stay in Russia, particularly in the Urals, because you cannot find such language from a distance”.

Every artist has their own social, economic, and emotional circumstances. For many, there are certain obstacles in continuing work, as frustration and self-censorship do not help creative processes. Kristina Gorlanova, an artist and the director of the Ural branch of the Pushkin State Museum, says: “My ability to work as an artist has been blocked since February, although six months have passed already. I already feel self-censorship. New laws about discrediting Russian army forces have very flexible rules; therefore, it’s hard to predict what is still legal and what is not. I cannot even think of activist or antiwar projects, nor find a medium or a form to work with. My scream unexpectedly became silent.”

At the same time, income rates have decreased. Important to mention: there is no such thing as a state grant in contemporary art for an individual. There are fewer commissions and less support from international institutions like international cultural funds and agencies due to the threat of receiving any money from a non-Russian institutional body and the subsequent threat of being recognized as a foreign agent.

Elena Anosova, an artist and photographer, based in Moscow and Irkutsk, says: “I used to curate a project for an international online journal dedicated to arts and culture. The journal was forced to close in March under threats of punishment for all its Russian-based contributors. In August, it was recognized as an unwanted organization, which means that I cannot mention it in the territory of Russia or in my portfolio. Not only that, I don’t have this job now, but a big part of my curatorial activity has vanished.” Anosova also used to work as a photographer for several foreign media operations in Russia. Now they cannot pay her, but that’s not the main problem: she would still work for a foreign organization. Such organizations cannot protect their contract workers; they don’t offer working visas or protection in case of emergency.

In conclusion, Anosova says: “I see my main mission now in teaching and mentoring. I know that young artists have no one to ask for advice at the beginning of their careers, and I aim to support them. After the war broke out, I considered giving up: what could I give them? What networks could I provide for them now? But I changed my mind. I see meaning in this.”

Considering the practical side of artistic work, many European neighbors of Russia, such as Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the Czech Republic, restrict Russian citizens from traveling through their countries. Even before the problems with obtaining, even applying for, visas and international travel, due to sanctions, there were no direct flights to Europe and many other countries, and land borders were getting less available. This reminds me of the old practice of quarantining plague districts with all of their inhabitants, whether infected or not; it is hard to believe democratic defenders of human rights would apply the same strategy today.

As it is widely known, payment or credit cards issued by Russian banks are not working in most foreign countries due to the suspension of Visa and MasterCard services. Therefore, while traveling abroad, holders of such cards can only use cash, which is not a big problem in most places, except in countries with mostly digital payments (e.g., Sweden).

Another thing that became unavailable is professional software: Adobe, Google, Microsoft Services, etc. As international transactions became impossible, there was no straight way to use licensed versions of them. As a photographer, Elena Anosova points out, “I respect copyrights and authorship. My Adobe Photoshop subscription, which I have used for the last 20 years, ends in November, and then I must figure something out—ask my friends abroad to make me a new account, for example. I’m forced to choose between being an asker and a thief. An artist might need to use specific tools to make art sensitive to recent situations. I want to pay for it but can’t buy it.” Anosova questions how it is different from other discrimination based on formal grounds.

I see my main mission now in teaching and mentoring. I know that young artists have no one to ask for advice at the beginning of their careers, and I aim to support them. After the war broke out, I considered giving up: what could I give them? What networks could I provide for them now? But I changed my mind. I see meaning in this.

However, for the time being, practical sanctions appear to be at a level of inconvenience and complexity rather than becoming the disaster that was initially anticipated. It seems that for the ones who stay, there are not many distinctions between the oppressive actions of the state and external sanctions. Sometimes they even complement each other in their effect on an ordinary citizen.

Widespread worries about the “cancellation of Russian culture” do not turn out that roughly either. “I have seen statements to cancel Russian cultural practitioners in general, but it has never been addressed to me personally,” says Gorlanova. "We face more positive examples. Among the artists I know personally, no one has experienced any cancellations, although I’ve heard of such cases.”

However, this is not to say that international activities haven’t faced any problems. Some projects involving Russian artists were canceled or postponed." I had the invitation to participate in one exhibition in Italy last spring, but it was canceled," says Gorlanova. “They said they do not continue this project as it has lost actuality. Now I do not receive any invitations, only from some local galleries focused on online sales. I cannot react to their offers”.

Some international institutions are still working with artists they had invited previously. “The Netherland gallery that represents me didn’t terminate our contract,” says Anosova. “In spring, they made an exhibition with my yellow-and-blue still life photography. All the works were sold, and the money raised went to a local refugee support foundation. I presented these works anonymously, as I could get imprisoned for them in Russia. My second gallerist from Portugal also supports me on both a professional and personal level.” This situation is similar for many: although foreign colleagues remain friendly and understanding, artists are simply not invited to participate in exhibitions anymore. Anosova says that she doesn’t receive any invitations to international exhibitions, although foreign acquaintances send her messages of support, saying words of solidarity. “I received a request of interest to participate in a project from a Norwegian photographer. It is an individual initiative; something is still possible on a peer-to-peer level.”

As a director of a museum branch, Gorlanova says: "International artists decline participation for different reasons: some are afraid (or not eligible) to work with a state institution; others are afraid to travel to Russia. Also, travel costs have risen, so we no longer have room in our budget for international participants. The last international artist left on February 25; they were sound artists-in-residence from the UK. Since then, we haven’t had anyone from abroad, and there are no plans for it."2

Understandably, Ukrainian artists now decline to participate in any exhibition that is in any way connected to Russia (sponsored by anyone affiliated with the country, having Russian artists and curators on their list of participants). It means that international organizers suspend or postpone work with them despite their neutral or even sympathetic stance toward certain Russian artists or art practitioners.

The sanctions affect not only the ones residing in Russia: for example, the withdrawal of payment systems makes it impossible for people with the main income in Russia to receive it outside of it. It could work the opposite way as well, as Sasha Rotts from an artistic duo SASHAPASHA (together with her partner Pavel Rotts), says: “I go to Saint Petersburg quite often as I have a family there. Now I cannot use my Finnish card in the territory of Russia, and I don’t have any savings in my Russian accounts”. Sasha has resided in Finland for the last seven years and studied art at Uniarts Helsinki. Before the war, she was planning an exchange semester in Estonian Kuma; now, the organization does not accept students of Russian origin. However, in contrast, Pavel has just received a grant from the Estonian Cultural Endowment Kulka for his artistic project, which he especially rejoiced in as proof that the situation is not too bad.

In general, Sasha and Pavel do not recall any negative experiences of being Russians in Finland regarding professional relationships and activity. Their local peers and colleagues express only sympathy (despite an incident of hate speech in everyday life). However, even being outside of their home country feels like being inside the conflict and a part of it.

Likely, we will not see the full impact of sanctions until later this year or next year, as they have a long-term effect and could be evaluated later this year or next year. However, it deepens the existing injustice and inequality: at the end of the day, the ones with less power and fewer resources—the precarious ones—get affected the most. Considering the diversity of situations Russian art practitioners are in, it is especially weird to read articles by international media resources where they are presented as a homogeneous mass, mixing up pro-Putin artists affiliated with state institutions, official culture with stable state budgets and enormous power, and independent artists.

Understandably, Ukrainian artists now decline to participate in any exhibition that is in any way connected to Russia (sponsored by anyone affiliated with the country, having Russian artists and curators on their list of participants). It means that international organizers suspend or postpone work with them despite their neutral or even sympathetic stance toward certain Russian artists or art practitioners.

Roman Sakin, Undrawn Sculpture Project for Patriot Park on the Occasion of Self-Censorship, 2022

3

In an immediate situation, you reevaluate, what is realistic, what is applicable, and what is bearable to you, and you might make many unpleasant discoveries about yourself (which I did). So, if you are sitting there in comfort, take your shiny and warm white coat off before giving advice and making judgments.

First days of the war, my Finnish colleagues and HIAP Connecting Points programme curators Miina Hujala and Arttu Merimaa posted this statement condemning the war and proclaimed to keep on working with art practitioners who opposed it. I was thankful, yet a bit surprised, as it seemed too obvious that artists were not to be blamed and everyone would know art workers were against the war. These days, when Instagram was still available without a VPN, I chatted with my German artist friend and mentioned that many Russians are against war. She asked me if she could make a screenshot and post it on her social media. I was again like, “Why would you share such obvious things?” She explained that some Germans think the whole of Russia supports the war. It was hard to believe, either. In a few days, the shitstorm started. I was too blind to guess what was going to happen.

When a conflict arises, we tend to think of the other side as less human. “How could such awful things happen still in the XXI century?” People are, in general, the same species. The difference is mostly in their circumstances, backgrounds, and context, which others might not know about. Some are attempting to avoid the invisible yet deeply hidden fear of actually being the same species by dividing, disengaging, and labeling (in our case, “Russians are a nation of slaves,” “Russians are merely cowards,” “Russians run from responsibility, not mobilization,” and so on). If things like this could happen today to others, could it possibly happen to us too? Can the society I live in, or even me, become so ‘evil’ too?

We grew up reading fairytale narratives where the good is celebrated while the evil is punished. It is very tempting to apply the same strategy to real life by simplifying the diversity of circumstances. It allows us to practice moral privilege (as Elham Rahmati puts it in her quick and responsive editorial for NO NIIN March issue) or, as we call it in Russian, to ‘wear a white coat’ (which is close to ‘be on a high horse’). Be heroic, go to the streets, risk imprisonment – it’s nice to give such recommendations from a safe place (I would probably do the same). In an immediate situation, you reevaluate, what is realistic, what is applicable, and what is bearable to you, and you might make many unpleasant discoveries about yourself (which I did). So, if you are sitting there in comfort, take your shiny and warm white coat off before giving advice and making judgments.

I have no universal answers or solutions, and I do not believe anyone who claims to have them. However, we can think of an approach that might change how we view things. We cannot consider any group of people to be homogeneous. Neither are all Russian artists innocent victims of their own state nor are all Russian people evil-minded barbarians; not all are any one thing; they all have different points of view, values, circumstances, conflicts, illnesses, etc., while being of the same humankind. If you claim solidarity, it should be based on shared opinions and views, not the country of origin. If you defend human rights, apply them to all human beings in a non-discriminatory way. If you aim for acceptance of nonhuman agents, start with human ones.

Searching for ways of coexisting starts with attempts at mutual understanding, acknowledging differences while looking for similarities. The way to form a community is to share common needs and values; this could become a ground for building transnational solidarities.