Eveliina Tuulonen is the Communications and Gallery Coordinator at the Pro Artibus Foundation and its Sinne gallery. In addition, she manages and curates the temporary art space Sports Hall Window.

I interviewed artist Nastja Säde Rönkkö on the occasion of her exhibition Those Who Kept the Light (2022), on view at Turku Art Museum, which opened in June this year. The exhibition features a series of ten poetic videos, each lasting 5 to 9 minutes, inspired by texts written in 2020-21 that explore the sea, along with related myths and stories. The series combines visual excerpts from the stark, barren seascapes of northern Denmark and Norway with the artist’s voice-over. The works can be displayed as a 10-screen video installation, accompanied by sculptures and a soundscape, or, as in the Darkroom space at the Turku Art Museum, as a single-channel projection showing the videos sequentially.

As I watched the series, each video unfolded like an independent poem, with its own distinct theme and narrative. When experienced as an uninterrupted single-channel projection, they collectively transformed into a poetry book bound within a single cover. This collection of poetic videos invites the viewer to explore the delicate interplay between emotion and intellect, where the vastness of the sea becomes a metaphor for unspoken, uncontrollable desires—touching on themes of solitude, longing, and the deep connection between women and the sea. Observing these elements, I became eager to learn about the background and thought processes behind this work to better understand the emotional and conceptual depth of Nastja’s creative process.

EVELIINA: What led you to the shores of Denmark and Norway, inspiring you to write in the context of the sea and lighthouses?

NASTJA: What attracts me to the ocean is based more on the metaphysical and poetic rather than that which can be understood solely by science. I’m also fascinated by the idea of porous bodies, how our bodies are very watery and liquidy. My fascination with the ocean may be related to our desire to be part of a liquid state—of being—and I want to write about the uncontrollability of that.

I have long wanted to make a project about the ocean, seafaring, and lighthouses. My interest in lighthouse keeping began around 2015 when I was in the United States while working on another project. I visited several lighthouses on the East Coast, where I learned about the women who kept the lights in the 19th and early 20th centuries. I was impressed by how comprehensively this history was documented and preserved in libraries, a practice I hadn’t encountered in the Nordic countries.

When Lotte Juul Petersen from Kunsthal Rønnebæksholm invited me to undertake a project exploring feminism within the Nordic context, it felt like a perfect context to make this work. I wanted to investigate similar stories and histories in the Nordic countries, focusing on the roles women played in relation to lighthousekeeping. Often, these women were family members of the ‘official’ male lighthouse keepers—wives, sisters, and daughters who took on the responsibilities on their behalf.

Conducting the research turned out to be more challenging than I had anticipated. I discovered very little documentation available in Denmark and Norway on women lighthouse keepers—though there may be more that I couldn’t access due to language barriers and limited resources. So, I conducted interviews with the locals, mostly older people. Since the development of navigation in ships and the automation of light-keeping, the light-keeper profession does not exist anymore. All the interviews needed to be interpreted, and the stories were very fragmented. Nevertheless, the stories, with their details and emotional states, inspired me when writing the texts in the series.

Throughout my research, it became clear that lighthouse keeping was a respected profession, especially in Norway, where it offered the security of a lifelong government job. However, I was interested in exploring the deeper, emotional reasons that drew people to this isolated work.

In one of the videos, the main character initially gives practical reasons for becoming a lighthouse keeper but gradually reveals more emotional motivations. For instance, the line ‘my canned milk, and my lonely cow’ is based on a true story from Norway, where a lighthouse keeper’s only companion on a remote island was a cow. The cow provided both milk and companionship, with supplies and letters arriving irregularly due to harsh weather. I wove these elements into several of the scripts.

Why,

I ask and you say:

Stable salary, Decent, free house, Government job, Pride, Responsibility, Respect,

Why,

I ask and you say:

My sea, my waves, my wetness, my gliding waving flickering horizon, my dripping dropping melting swaying molecules, my slimy, crystalline, shimmering creatures and my muddy, scaly, teethy bottom-feeders and my rusty, old sunken anchors and my bright, light, harmless lanterns, and my guiding, shimmering, shining lights and my windswept whitewashed walls, and my damp, bland biscuits, and my stormy days, and my sailing ships and my capsized boats, and my heroic deeds, and my canned milk, and my lonely cow, and me and my horizon alone, and me and my wind in the grass, alone, and me and my whispering mussels, alone, and me and my little black dog, alone, and me and my rotting fish-smell, alone, me and my isolation, and me for this place, my space, and me and the sea that takes, and the sea that gives and the depths of the ocean and the waves within, false calmness, me and my lovers, my mistress and no distress

Excerpt from the text in video Those Who Kept the Light (Why)

How did you integrate mythology and storytelling in exploring the relationship between women and the sea?

I integrated mythology and storytelling by drawing on ancient sea myths, legends and creatures, particularly those involving female figures like the seal-woman of the Faroe Islands, as well as stories of sirens and mermaids. Through these narratives, I explored the symbolic and often queer connection between women and the sea, weaving these themes into scripts and poems in the context of women who kept the light.

What fascinates you about lighthouses and the sea?

For me, a lighthouse is a space where you can be alone with the ocean surrounding you. Some of the lighthouses I visited, especially in Norway, were very remote, and that remoteness allows you to hear and listen to the ocean. Hearing the sea is calming and emotional for me. The lighthouse forces you to be alone with your emotions and without distractions.

One of the emotions evident throughout the ten videos was desire – longing for someone or something and the tension that desire creates. How does the sea serve as a catalyst for exploring longing and desire in the series?

In the specific context of the sea, I wanted to explore what desire is, how it can be directed towards a person, a thing, or an entity, and why it can be challenging to articulate. The most fascinating emotions for me are those that are open, unexplored, in-between, and uncontrolled. Desire often encompasses these aspects, reflecting a longing for what is not yet fully understood or articulated. Queer desire, in particular, often navigates spaces and relationships that defy traditional societal boundaries. At sea, I feel a lack of control; the vast, open, and powerful nature of the sea mirrors this kind of longing or emotional state. In the space of desire, one can give oneself away to another in a way that is beyond one’s control, reflecting a yearning for the unexplored and the potential for transformative experiences.

In this project, the emotional insights from my interviews subtly influenced my creative process, blending with my personal and imaginative narratives set at sea. I drew from both my own experiences and those shared by others, capturing themes like desire, loneliness, and loss. I carefully record my thoughts and reflections over time and refer back to these notes to incorporate specific emotions into my work, enriching both the written and visual elements of the project.

I noted lists and repeating of words and associations in your work. How do you structure your thought process when generating text-based outputs? Do you follow a specific method or outline, or does the creative process unfold more organically?

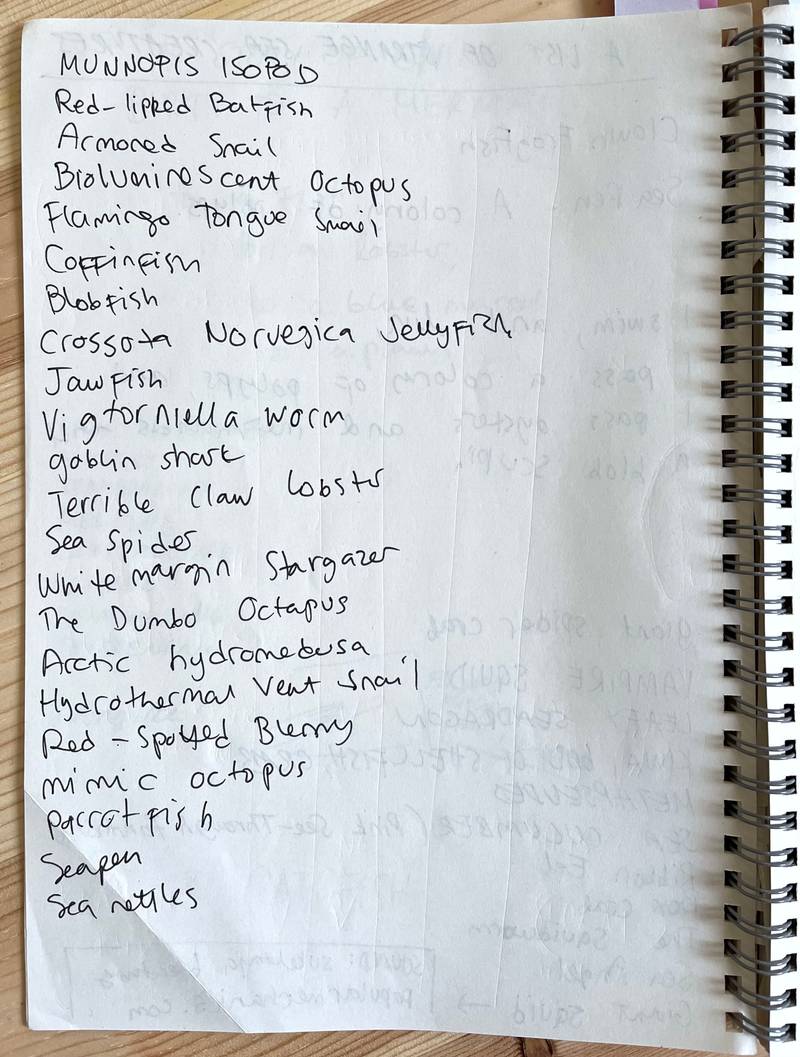

Writing is always central to my work and the beginning of every process. I write a lot. I have notes on my phone, in notebooks, sometimes on random pieces of paper. I write observations, thoughts, notes on books I read, sometimes diary. I love lists, and I write a lot of lists, or just sentences that resonate. With the context of this project I was researching things such as funny sounding sea creatures, such as a sea cucumber or a vampire squid, which are then written into the story. Then once a broader idea or concept emerges, I begin to select and refine these notes through extensive editing, re-writing and trying to carve out a narrative or an emotion that carries the script. For me, language, alongside music, is one of the most powerful tools to convey emotions.

In the visual aspect of the process, the text may present challenges in finding appropriate visual elements to complement it. Occasionally, a visually compelling element might be incorporated into the text even if it wasn’t part of the original plan. Conversely, I might need to remove text if it doesn’t align with the visual elements of the work.

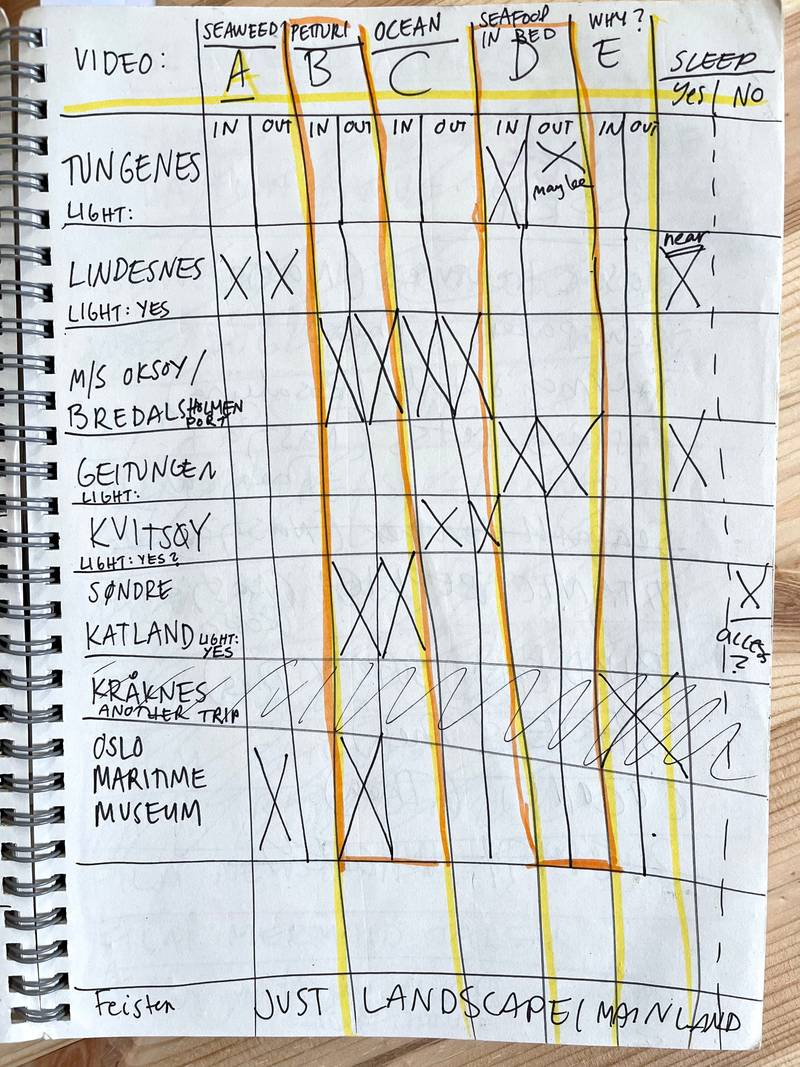

For this specific project, I used my sketchbook to capture notes from interviews, lists, and various details that eventually become sentences. The sketchbook also includes notes on site visits, filming locations, and logistics. For example, it contains pragmatic notes like whether to film inside the lighthouse and the best times for filming.

I chose to show this because we often see only the polished end result, while the actual process is typically lengthy and messy yet very fascinating.

Pages from Nastja Säde Rönkkö’s sketchbook when working on Those Who Kept the Light | Photo: Nastja Säde Rönkkö

Can you elaborate on the significance of the northern seascapes in your work?

The northern seascapes hold a profound significance in my work because I am deeply drawn to their wild, lonely, and barren nature. Their remote and often uninhabited qualities resonate with me, offering a raw environment that is both isolating and inspiring.

How do you approach choosing the atmosphere of the music for a specific video?

Choosing the atmosphere of the music for a specific video involves a process similar to writing. I start by listening to the possibilities there are (with the composer) and identifying songs or sounds that align with the mood and tone I aim to create. Sometimes, a particular piece of music inspires the visual and textual elements, and I edit the work to fit it. However, I am cautious not to let the music dominate to the point where my work feels like a music video.

I have collaborated for years with Timo Kaukolampi, whose music is featured in this project. Additionally, I worked with sound designer and musician Janne Masalin to fine-tune the audio. Our approach is closely tied to the text; for instance, if the narrative involves a drowning scene, we consider what kind of music would best convey that experience. Music is a crucial tool in my work, as it, like text, helps articulate and guide the viewer’s emotions through the visual elements, which I find fascinating.

Working in communications, I always think about the context of the work and what kind of exhibition text is next to it. For your exhibition in Turku Art Museum, I read the exhibition text in advance. It guided me through the work and gave me themes and elements to look for. For example, I wanted to ask about climate change, which is mentioned in the exhibition text even though it is not directly discussed in the work.

Yes, even though climate change is not explicitly referenced, it is there as a strong undercurrent of the work, providing an essential context in which the works have been created. One book that greatly influenced me for this work was Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us, published in 1951. Already then, the book warned about the state of the oceans, and did it in a very poetic way.

When it comes to giving context to works, my other current exhibition Survival Guide for a Post-Apocalyptic Child at Helsinki Art Museum, tackles different emergencies more directly, and the exhibition text helps the viewer to become aware of the clear structure going from A to Z with the theme of survival guide.

If a work is very research-based, there are things the viewer won’t get without explaining the background of the work and where it stems from. At the same time, even though Those Who Kept the Light has its basis in research, it focuses more on personal poetic narratives and can be viewed without a guiding text. One can choose if they want the text to function as a guide to the work.

Can you elaborate on the techniques you used to create an intimate connection between the viewer and the sea in your videos, particularly in the way they have been presented at Turku Art Museum? How did you aim to evoke this emotional bond?

To create an intimate connection between the viewer and the sea, I chose to present the work as an uninterrupted single-channel projection, allowing the videos to unfold like a continuous, immersive journey. In Turku, the large projection screen in the black box and the enveloping soundscape enhance this experience. The barren northern imagery and sounds of the sea set an atmospheric backdrop, while the voice-over and poems aim to draw viewers into a reflective space.

By giving the sea and its creatures a voice and presence of their own, I wanted to evoke a profound sense of longing and connection that transcends emotional boundaries – encouraging viewers to feel not just as observers, but as participants in a shared emotional space.