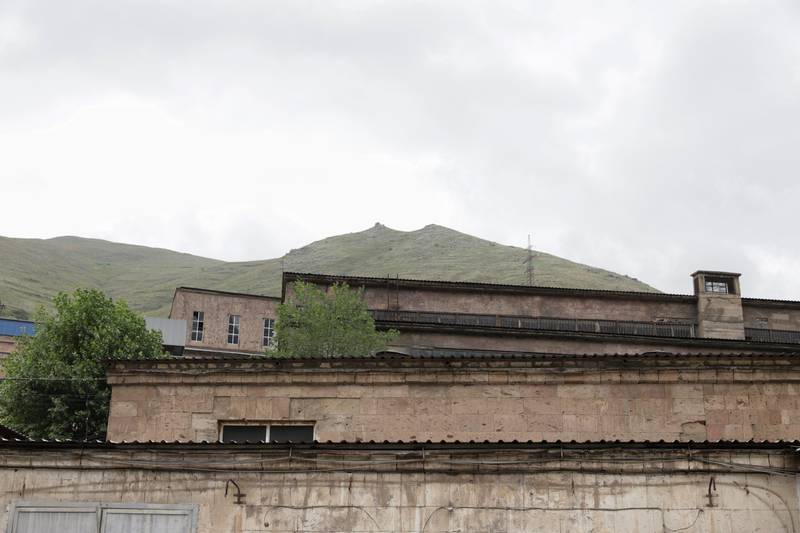

A view of the open-pit mine in Kajaran, 2024

Gayané Ghazaryan is a documentary photographer and independent journalist based in Yerevan, Armenia. Drawing on oral history methodology and visual storytelling, her work primarily explores issues related to young people and the working-class in Armenia – from post-war realities in border villages to the impact of environmental destruction on local communities.

On January 31st, workers at the Zangezur Copper-Molybdenum Combine (ZCMC) in Armenia’s southern Syunik region launched a wildcat strike to demand safer working conditions and adequate wages. Unprecedented in scale since Armenia’s independence1, the eleven-day strike was nothing short of revolutionary, as over 2000 workers self-organized in defiance of corporate authority. They brought to a halt the operations of a profit-making machine that had run around the clock for decades, an entity often shielded from criticism by its status as “the largest taxpayer in the country.”

What began as a call for dignity and basic protections was first met with institutional indifference, followed by corporate intimidation and retaliation. The strike’s “illegality” was swiftly condemned by ZCMC’s management, the Confederation of Trade Unions of Armenia and the neoliberal state itself, even though workers had previously raised their concerns several times before and had attempted to gain trade union approval for a formal strike. On the eighth day of the strike, ZCMC unlawfully fired eight workers for their active involvement in organizing and negotiating. Although the strike came to an end with the promise2 that no worker would be punished for taking part in it, eight workers now face a lawsuit3 with ZCMC demanding 4 billion 758 million AMD (approximately $12,390,060) “as compensation for the damages incurred by the company.” As Shavarsh Margaryan, one of the key figures of the strike, poignantly noted in one of his recent social media posts, “When you work quietly, you’re not valued. But as soon as you begin to speak out, you cost billions.”

Some of the industrial facilities of the Zangezur Copper-Molybdenum Combine in Kajaran, 2024

The reasons for the strike and the outcomes that followed not only speak of the state of workers’ protection in Armenia but also the internal colonial logic of mining in the country. For years, Armenia’s neoliberal development policy has portrayed large-scale mining as a pathway to economic growth, justifying it through promises of new jobs, foreign investment and a rising GDP, while environmental and human costs are externalized and profits are funnelled upward to the elites and foreign stakeholders. Meanwhile, criticism of the mining industry tends to focus mainly on environmental issues: deforestation, water pollution and toxic tailings dams. While these are urgent and valid issues, this narrow focus often obscures the colonial and class-based dimensions of mining in Armenia.

Mining giants like ZCMC don’t just extract minerals and natural resources. They exploit the labor, land, bodies, health and other resources of the working-class4. While people’s labor and dispossession of the land generate profit for local and foreign capitalists, it’s the local communities that bear the brunt of environmental destruction and the toll of this exploitation.

A view of the open-pit mine in Kajaran, 2024

Whose mine?

ZCMC, located in the town of Kajaran, began operations in the early 1950s under Soviet rule. Throughout the Soviet era, it was state-owned and provided stable employment, housing and social infrastructure for workers, many of whom moved to Syunik from other parts of Armenia5 or the USSR. Conversations with workers who’ve been employed since the Soviet years often highlight a deep contrast between past and present labor conditions. Moreover, the town’s social and cultural life was not exclusively tethered to the mine: alternative avenues for employment, education and recreation existed (e.g., the public pool that was later demolished by ZCMC, or the youth camp that has now turned into a hotel catering to ZCMC’s current Russian management).

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and Armenia’s independence in 1991, like many other state-owned enterprises, the mine went through privatization during the neoliberal reforms of the late 1990s and early 2000s. Since then, ZCMC’s shares have been acquired by various companies with ties to foreign capital (e.g., the German-registered Cronimet Mining, which acquired 60% of shares, or several Russian nationals registered in the 2024 “Real Owners Declaration”).

Shavarsh Margaryan addressing fellow workers on strike, February 2025

When locals in Syunik speak about the mines operating in their towns, it’s striking how often they refer to them by the nationality of their owners: “When the Canadians came,” “When the Germans took over,” “With the Russian ones….” Labeling the mine by the passports of its executives or shareholders reveals a population that feels acted upon by global forces rather than in control of its natural resources. This naming, in a way, becomes a subtle grammar of dispossession.

In fact, although the February wildcat strike’s main demands were safer working conditions and a pay raise, the conversations I had with workers at the encampments near the plant revealed deeper frustrations. Many spoke of the discriminatory treatment they received from the Russian6 management, expressing a sense of being second-class in their homeland. “They don’t even greet you,” as one of the workers said. Several noted with quiet indignation that when Azerbaijan attacks Armenia, it is THEM—the Armenian workers—who take up arms to defend the border and its people, NOT the foreign executives who retreat to Yerevan or even abroad on weekends, avoiding the industrial town they profit from. Kajaran, in their eyes, has become a closed-loop economy: one where the sole function of the population is to wake up, work and extract value. This dynamic becomes more alarming considering Syunik’s geopolitical significance with the renewed threats from Azerbaijan and the ongoing negotiations around the so-called “Zangezur corridor,” a euphemism for a new phase of land grabs and further colonization.

Striking workers at the encampments around ZCMC premises, February 2025. Photo: Gayané Ghazaryan

It’s important to note, however, that when it comes to extractive industries, colonial relationships in Armenia are both external and internal. For decades, the Armenian state has functioned as a facilitator of extractive practices that prioritize profit over the well-being of local populations, all while presenting mining as a symbol of national development. In doing so, they replicate the logics of colonial extraction: accumulation by dispossession masked as progress and the silencing of those most affected. In the case of pre-2018 regimes under the rule of the Republican Party, high-ranking officials and their ties profited from mining through state-enabled privatization, oligarchic control of shares and political protection of elite interests tied to the mine. So what cultural anthropologist Tamar Shirinian (2017) wrote in her “Decolonizing Armenia: Metropole and Periphery in the Era of Postsocialism” comes as no surprise:

“While socialism was not necessarily felt as colonialism for Armenians, post-socialism is feeling a lot like it. This colonialism, however, has much in common with processes of postcolonialism in the parts of the world dominated and occupied by Western forces until the mid-20th century. This postcolonialism is not necessarily a lingering of colonization, or the residual effects of colonization, but the after-effects of a government that arose from the ashes of the socialist project. Postsocialism, in other words, is felt by Armenians as a more entrenched form of colonization than socialism ever was. The colonizer, in this instance, however, is this new mafia-state.”

In 2018, mass protests swept across Armenia in what came to be known as the so-called “Velvet Revolution,” a nonviolent uprising that led to the resignation of Prime Minister Serzh Sargsyan and brought opposition figure Nikol Pashinyan to power. These protests were driven by widespread anger toward the country’s oligarchic system, corruption and the deepening economic inequality. For thousands of people, including the naive 21-year-old me, it was a moment of hope for genuine change in the country that would break away from Armenia’s oligarchic past.

Yet when it came to economic policy, Nikol Pashinyan’s administration embraced a market-oriented, investor-friendly model of development. And even though Pashinyan’s government announced the acquisition of a 22% stake in ZCMC in 2022, this partial nationalization of the mine rarely translates into increased transparency, ecological accountability or the redistribution of wealth, as the government continues with the same policy of neoliberal extractivism. During the 11-day strike, for instance, instead of acknowledging the needs and demands of workers, the Minister of Economy encouraged the workers to resume their operations, prioritizing “economic growth” and “tax payments”. Moreover, the Amulsar gold mine project in the Vayots Dzor region, heavily backed by foreign capital (e.g., Lydian International), was initially suspended due to grassroots environmental protests but later endorsed by Pashinyan, eventually granting the company mining rights until 2039.

Toxic Landscapes

While workers in Kajaran continue their struggle for justice, better working conditions and dignified wages, communities living around the Artsvanik tailing dam prepare to cede more of their farmlands and orchards, as ZCMC plans to expand the dam and raise it by another 21 meters above the current permitted level. The toxic giant, filled with heavy metals, is located about 35 kilometres from Kajaran, where the mine is, and only 6-7 kilometres from the town of Kapan. This is the fourth and largest dam used by ZCMC to dump mining waste. Built in the early 1970s, the dam contained approximately 300 million cubic meters of waste as of September 2024, as corporate greed pushes for relentless 24/7 extraction.

Partial view of the Artsvanik tailing dam, 2024

“We used to have orchards back in the day, but now everything has to be bought from a store.” This is a recurring sentence in the narratives of the villagers who had to give up their land to make room for the growing monster that’s now poisoning their soil, water and air. Many residents of the Artsvanik village were offered a one-time compensation that barely covered their losses. Today, ZCMC also pays a monthly sum of 40,000 AMD (approximately $100) to affected families, a payment that offers some short-term relief but creates long-term dependence. For many, it has become a trap: too small to live on, too crucial to risk losing. When I spoke to the villagers, many refused to raise their concerns publicly, as they’re afraid to lose this source of income.

Like many residents of Artsvanik, 63-year-old Anahit and her husband, for example, live off their pensions and the monthly compensation of 40,000 AMD from ZCMC. They mostly spend this money on food and other essential household expenses. In the past, they had an orchard and land for livestock, but most of it ended up under the tailings dump, and what little remains is uncultivable due to water shortages, a problem that has only worsened with the dam’s expansion.

The consequences of land loss are especially hard for women. With no farmland left to tend and no meaningful employment opportunities, many find themselves locked in economic and social limbo. “I studied textiles. Back in the day, there was a sewing factory in Artsvanik, and we worked at the sewing factory. Then the factory shut down, and we had to stay at home without work. There is no work here now,” Anahit told me.

A local woman harvesting potatoes and onions from her small plot of land near the dam, 2024

Women and children collect drinking water from the water spring, 2024

Although ZCMC continues to operate and expand the tailings dam, village residents have, for years, faced neglect of basic infrastructure by both the combine and the state. Against the backdrop of massive mining infrastructure, many villagers still lack basic amenities such as permanent access to water and gas. In many parts of the village, running water has either been entirely unavailable or accessible for only one to two hours a day. This shortage particularly impacts women, who, as the primary bearers of caregiving and domestic labor, are forced to walk long distances on foot to fetch water. In February 2025, pipes for a water system had already begun to be installed, and according to the villagers, they’ve been promised regular access to running water by fall.

In the past, protests against the expansion of the dam gave rise to moments of resistance. It was thanks to collective resistance that villagers were able to secure limited compensation for their losses. But during my recent visits, a quiet resignation seemed to hang in the air. Many now speak less of stopping the dam and more of surviving its presence. What remains is a demand not for justice in its fullest sense, but for at least fair compensation for the harm already done. One woman I interviewed perhaps captured this shift with unsettling clarity: “The government says, ‘It’s better not to have agriculture but keep the mine.’”

From the extraction of minerals to the exploitation of labor and land, mining in Syunik (and Armenia more broadly) operates through a deeply colonial and exploitative logic, sanctioned by both state and capital. The voices of Kajaran’s workers and the silenced frustrations of Artsvanik’s villagers should be reminders to center the people whose lives and lands are being sacrificed.

All images courtesy of Gayané Ghazaryan.