Reviews

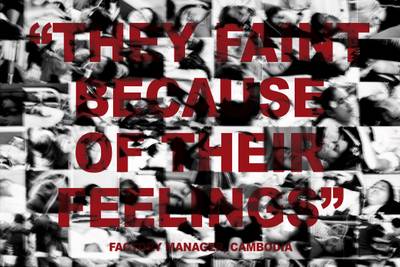

If the problems that individuals face in their personal lives are rooted in systemic issues, then it is unrealistic to expect them to find lasting solutions solely through individual self-improvement efforts. Individual change is not simply a matter of personal effort but is also shaped by the broader social conditions that individuals find themselves in. Abril’s work highlights this hypocrisy of the oppressor in a perverted patriarchal society in which women are blamed and ridiculed for showing symptoms of distress—Mass Hysteria.

READOur Bodies Protest on Our Behalf: A Review of ‘Laia Abril – On Mass Hysteria’

Laia Abril’s work On Mass Hysteria at The Festival of Political Photography challenges the focus on individual diagnosis, prompting the question, can photography be a tool for social diagnosis and change?

Is it possible for a white institution to say it presents the articulation of people of colour? Is it possible for a non-indigenous institution – which through its national identity participates in the theft of indigenous artifacts and bodies – to say it is giving a place to the ideas and thoughts of the indigenous people? How can an institution talk about the disappearance of universal value judgements and the need for diversity in values within society when it is the final harbinger of value judgements and its permanent staff, which wields this power, is itself not diverse? How does it claim to judge what “diversity” or the subaltern articulate and what of this articulation should be in a museum? What are these claims based upon? The choice of artists? The act itself of legitimizing a voice? Unless the very foundations of this system change, we are all just playing along.

READProblematizing Perspectives and Positions: A Review of ARS22

How can the subaltern be meaningfully and non-performatively brought into the museum?

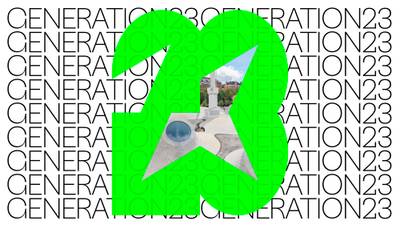

In an art world obsessed with the urge to find the next new thing and benefit from it, can a sleek, high production value exhibition showcasing the work of 15 - 23 year old artists challenge the love-hate relationship with the youth? Generation 2023 is balanced and diverse, but its fixation on youth is double edged.

READThere Are No Enfants Terribles Here: A Review of Generation 2023

In an art world obsessed with the urge to find the next new thing and benefit from it, can a sleek, high production value exhibition showcasing the work of 15 - 23 year old artists challenge the love-hate relationship with the youth? Generation 2023 is balanced and diverse, but its fixation on youth is double edged.

Close Watch exhibited at the National Finnish Pavilion at Venice Biennale, 2022, is a multimedia installation that, at its core, utilises the artist themself as an embodied intervention within a focused area of artistic research and apparent critique. In the context of this work presented as an exhibition at the national pavilion and its implications of somehow representing Finnish Art, this text seeks to question whether issues pertaining to embodiment and social intervention – and by extension, research conducted and artistic practice developed through it – can ever be free of the power relations implicit in the political, identity-driven understanding of society today.

READWho Watches Whom? Ruminations on Power, Gaze, and Field Through Pilvi Takala’s Close Watch

Ali Akbar Mehta’s review questions whether issues of embodiment and social intervention can ever be free of the power relations in the political, identity-driven understanding of society today.

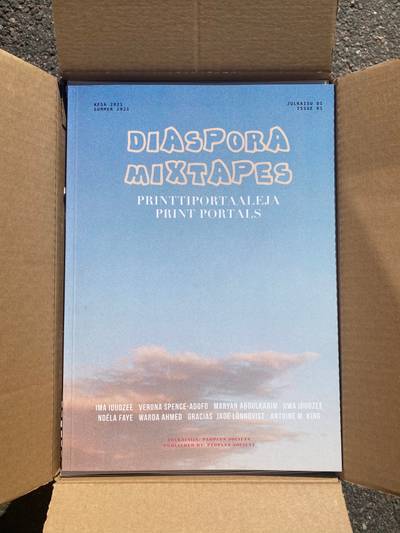

In this piece, I explore the interrelatedness of visuality, black displacement and black diaspora. Diaspora Mixtapes makes apparent the efficacy of visual representations as an artistic genre that implicitly addresses questions of border regimes, queer belonging, and self-representation. Furthermore, Diaspora Mixtapes exemplifies the contemporary inclination to make visible black cultural exchanges.

READDiaspora Mixtapes: Towards a Politics of Black Filmmaking

Analytical review of ‘Diaspora Mixtapes’ an art-house documentary reveals what it means to politicize the visual.

Knowing the genealogy of women’s resistance in Iran since the turn of the century helps us see recent events not as unprecedented ruptures and a sudden awakening of women in an archaic patriarchal society but as the accumulation of multiple resistances throughout our modern and contemporary history in the face of an ever-shape-shifting patriarchy.

READRepresentation of Disobedient Bodies: A Critical Reading of Shirin Neshat’s Visual Language

Comprehending the discrepancy between the representation of the multitude of experiences of people’s protests in Iran, reflected in their own photographic and moving images, and the detached artistic creations of diasporic artists like Neshat.

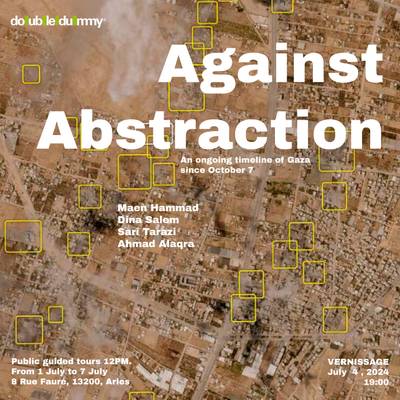

An activation by Palestinian artists Maen Hammad, Dina Salem, Sari Tarazi, and Ahmad Alaqra was hosted at DoubleDummy, Arles, between July 1-7, 2024, during the opening week of the Rencontres d’Arles. It conveys a timeline of the ongoing genocide in Gaza using information shared via alternative messaging platforms like Telegram.

READRadical Re-imagining of Visual Order Amid the Ongoing Genocide of Palestinians: A Review of ‘Against Abstraction’

An activation by Palestinian artists Maen Hammad, Dina Salem, Sari Tarazi, and Ahmad Alaqra was hosted at DoubleDummy, Arles, between July 1-7, 2024, during the opening week of the Rencontres d’Arles. It conveys a timeline of the ongoing genocide in Gaza using information shared via alternative messaging platforms like Telegram.

The wealthy are equated with such minorities as if being wealthy were a specific cultural phenomenon or even an identity based on a form of discrimination. Veering through notions of whether wealth improves mental well-being or is taboo in Finnish society, Eetu Viren peruses the exhibition’s banality and ridiculousness to expound on questions of wealth and power and why the Finnish National Museum hosted an exhibition that characterizes the wealthy as a “minority group.”

READThe Poor Rich People: A Review of ‘The Philosophy of Wealth’

Eetu Viren on questions of wealth and power and why the Finnish National Museum hosted an exhibition that characterizes the wealthy as a “minority group.”

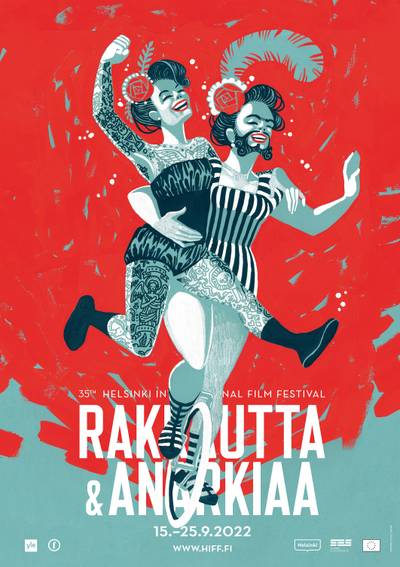

I could see a lot of love. But I was still trying to find the anarchy that breaks through and what it breaks through. I wondered if I should write about the positionality of the festival in what can be termed as its cultural intervention into events and processes that affect us today.

READFinding Anarchy: A Review of Helsinki International Film Festival

How can organizations dismantle power and operational structures within the world of film festivals to make them speak to the city’s various layers of inhabitants and their lives?