Reviews

ALJUB is a thoughtful and enjoyable provocation, bringing together sensorial pleasure and a space for the expansion of critical thought. In doing so, it also projects onto broader conversations about the politics of language, its evolution and uses, and how colonial power shapes it in its own favour – how narratives are structured to legitimise specific histories while erasing others.

READ(Hi)story of Lies: A Review of Claudia Pagès Rabal’s ‘ALJUB’

ALJUB, presented at Index, probes how language, paper, and power flow through History much like water, quietly shaping, dividing, and legitimising. This review also considers how Index’s curatorial approach and institutional framework support politically engaged projects, reflecting on the role of critical thinking within independent art institutions and the critical outcomes that can emerge from sustained collaboration between artists and curators.

The struggle and violence that When We See Us attempts to circumvent is not self-inflicted. The exhibition as a format presents liberal humanism’s trajectory, highlighting how it is, at its foundation, a vehicle for a particular genre of being. To highlight joy through liberal humanist grammars contributes to this trajectory. In times of concurrent genocides, in an effort to interrupt liberal humanism, it would be more honest to acknowledge and take a critical position against it.

READBlack Joy™ in the White Cube: A Review of ‘When We See Us’

Bringing over a hundred years of Black portraiture into view, the exhibition’s tonal optimism about Black self-representation belies the complex histories of race, power, and visibility it mobilises. What does it mean to celebrate “Black joy” within the architecture of liberal humanism and under the shadow of corporate complicity?

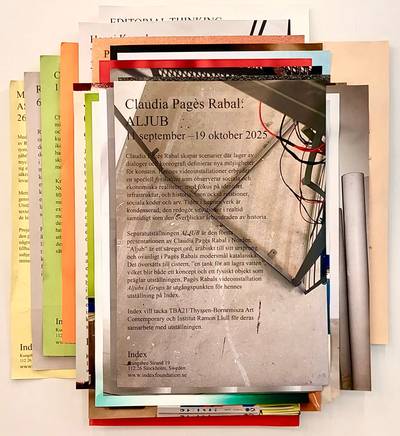

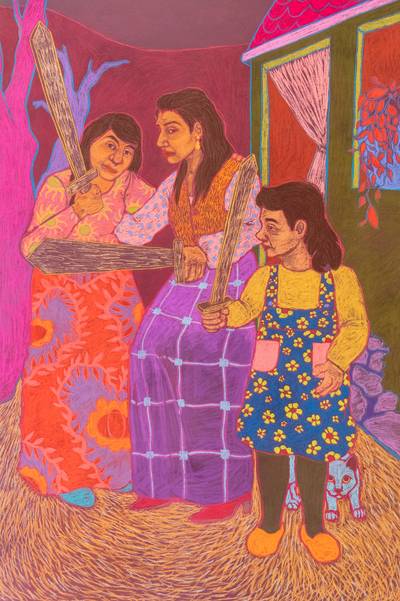

Bahujan narratives in media and popular culture are invariably mitigated through a savarna gaze that disregards Bahujans as people with agency, complexity, and vibrant histories of resistance. In such a milieu, Jyoti Nisha undertakes the immense and multifaceted task of unpacking the historical denial of Bahujan stories in media and popular culture, interrogating how history and mythology collude with contemporary violence.

READFutures Held Together by Memory: A Review of Jyoti Nisha’s ‘Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Now and Then’

Jyoti Nisha’s feature-length homage is a compelling love letter to the Ambedkarite-Bahujan community. It is an act of care, archiving, and resistance, preserving intergenerational stories of anti-caste struggle, both historical and contemporary.

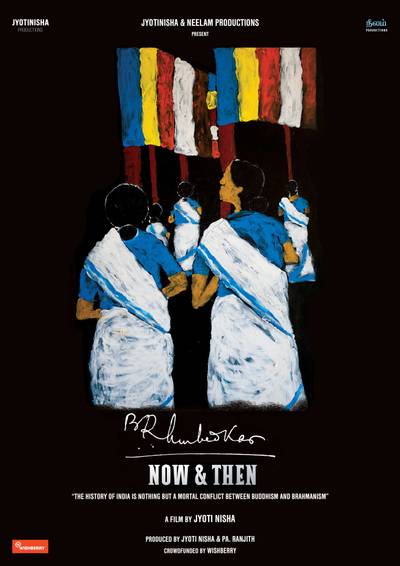

Aïnata (2018), shot in South Lebanon, is the debut documentary by the Lebanese research-based artist and filmmaker, Alaa Mansour. The memories being reconstituted in the film are those of Aïnata, a town in South Lebanon nestled within olive and tobacco farms, plagued for decades by Israeli occupation and violence.

READMemory and the Fractured Image: A Review of Alaa Mansour’s ‘Aïnata’

In her review, Shams Hanieh explores how Alaa Mansour’s film Aïnata (2018) uses visual fragmentation and reconstruction to more truthfully represent memory under colonial violence. When our world and histories feel so distorted, what other form could their representation take?

There is no universal ‘the’ trans body. Where does this article ‘the’ come from and what does it do? To us it seems that to look at something through the lens of ‘the trans body’ is claiming to know something that is situated in some imagined universal trans body – ultimately projecting one’s own body as that universal human in the trans context; the same universal human that the work claims to critically dismantle. White, non-disabled, thin, masculine and middle-class.

READThe Trans Body in Venice: A Critique of Universalising Transness

This review of Teo Ala-Ruona’s ‘Industry Muscle: Five Scores for Architecture’ explores the implications of universalising language, such as ‘the trans body’, in describing marginalised experiences within large-scale, nationalist, and artistic contexts, including the Nordic Countries Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale.

The notion of public intellectualism as a public good that ultimately benefits society seems to have been abandoned, while popular social media platforms have become a means of delivering finely tuned messaging, instrumentalising users and leveraging the interests of the “vectoralist class” who own them. As the critical arts sector adapts to the current challenging conditions, many will be paying close attention to Staal and BAK’s next moves.

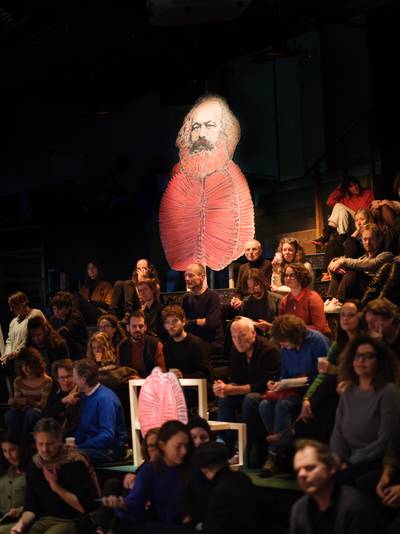

READArt in Critical Condition: A Review of BAK & Jonas Staal’s ‘Climate Propagandas Congregation’

Amid deepening global crises and rising state repression, Jonas Staal convened a gathering at Utrecht’s BAK—an institution well known for progressive art and political inquiry. Bringing together artists, activists, and thinkers, we reflected on the role of art in this era of climate catastrophe: resisting fascism, confronting genocide, and imagining alternative futures.

Moving away from the cool conceptualism common in biennials, the 5th edition boldly embraces anger, sadness, and euphoria. Presenting a diverse range of works that reflect the struggles of marginalized communities while also offering survival strategies, resilient tactics, and hopeful narratives, the biennale features artists from Hungary and Central-Eastern Europe, as well as international voices, creating a compelling blend of regional and global perspectives. This diversity aims not just to raise awareness but to cultivate empathy and solidarity.

READThe Storm Is Already Here: A Review of ‘5th OFF-Biennale Budapest’

The review explores how the 5th OFF-Biennale Budapest, celebrating a decade of independent art, fearlessly confronts themes of fear, prejudice, and societal unrest, championing empathy and solidarity in a landscape often hostile to such discourse.

In his remarkable 2019 debut feature film Soundless Dance, Raveendran narrates the horror of the Vanni genocide (2008-2009) through two physically and politically vastly different places. Thousands of kilometers apart, both lands are bridged by a young refugee who sleepwalks through them, neatly weaving them into a single landscape that is inhabited by a torn, oppressed and uprooted people who are seeking stability, safety and a future across these grounds.

READMourning from a Distance: A Review of Pradeepan Raveendran’s ‘Soundless Dance’

Though ‘Soundless Dance’ is now six years old, it is a film many Eelam Tamil viewers and others remain to date unfortunately unaware of. By inviting us to observe a genocide from outside its centre of violence, the director of the film artfully manages to show viewers the actual reach of weapons and the costs of state crimes to concerned and displaced people.

History, in the work of Amjad, is incomplete without memory and the collection of subliminal voices within the annals of time. Memory is not restricted to the singular phenomenon of evoking nostalgia, but is a significant conduit in Amjad’s work used to help construct and situate oneself in the present moment.

READSubliminal Spaces & the (Re)Collecting of Identity: A Review of Uzair Amjad’s The Terrain Between

Uzair Amjad’s The Terrain Between explores colonial legacies, migration, and diasporic identity through evocative paintings. By layering personal and historical narratives, the exhibit conjures subliminal spaces where memory, displacement, and transformation shape the collective present.

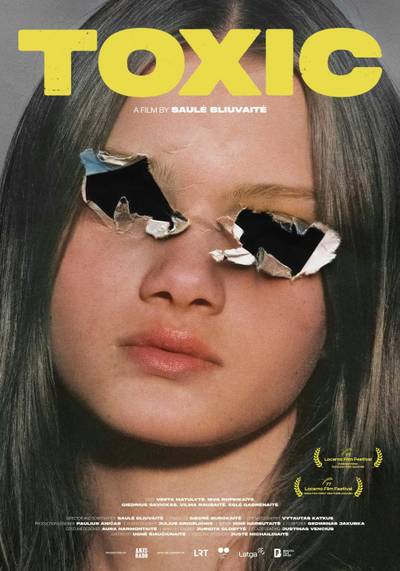

Toxic mirrors the spirits of a society learning to navigate freedom while haunted by an unresolved past. Here, the idea of the West glimmers like a distant oasis—a place of glossy dreams and bright promises that never quite materialise, as for many, those dreams soon meet harsh reality.

READA Dance of Intimacy, Ambition and Despair: A Review of Saulė Bliuvaitė’s Toxic

In Saulė Bliuvaitė’s film ‘Toxic’, friendship and rivalry weave together in a complex dance, an intricate play of support and silent competition. Filled with both violence and tender moments, in the film it emerges as a fragile lifeline.

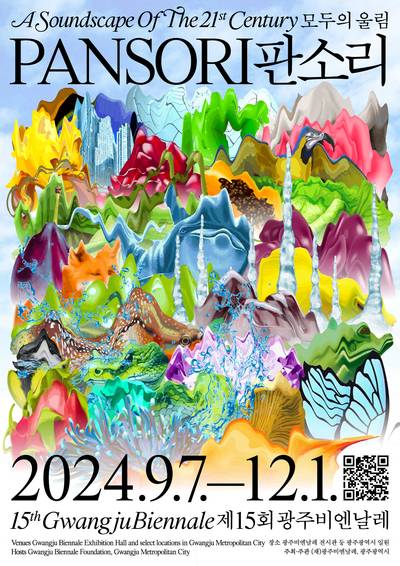

The main exhibition, “an operatic exhibition about the space we live in”, is housed in the Gwangju Biennale Exhibition Hall. Its galleries present significant challenges due to their modular white walls and vast areas to fill. This is likely why the main exhibition includes works by 72 artists from 30 countries. The 15th Gwangju Biennale is not the only large-scale exhibition to challenge the concept of a “static exhibition,” but it stands out for its innovative approach. The main exhibition shifts focus from the dominant sense of sight to other senses, particularly listening, based on the visitors’ mobility. Constructed as “a narrative,” the venues connect musical and visual forms.

READListening to the World: A Geopolitical Lens on the Gwangju Biennale

The 15th Gwangju Biennale, marking its 30th anniversary, focuses on sound and ecological themes. Rooted in South Korea’s democracy movement and the 1980 Gwangju Uprising, does the Biennale continue to uphold its founding declaration of a “living memorial” or sidestep the political?

Bulgaria as a space and a nation had a profound impact on the way I embody myself and shaped and reshaped my sense of national identity. To this day, I remember sitting on my grandmother’s lap in 2006 on New Year’s Eve in my house, awaiting the beginning of the new chapter in Bulgarian history—our ascension to the European Union. For a country that was not a direct participant in the colonial project of Western Europe and so often described as a part of the “margins” of Europe, this geography, which I was living in, would finally be put on the world map. Or so I believed.

READBulgarian Pavillion’s ‘The Neighbours’: Bridging the Memory Archipelago of the Bulgarian Communist Past

This is not a review of the Bulgarian pavilion but a challenge to deal with history’s silences, recognize my family’s past, and find the connections and bridges between my two bodies. One seeing and one actively articulating my positionality in the world in relation to the notion of nationhood, identity and language, which I was prescribed — Bulgarian Turkish.